Attakullakulla (Little Carpenter) and the Art of Diplomacy

In 1730, seven Cherokee men caused a sensation in London. Wherever they went—to the park, to the theater, to see the Crown jewels—spectators pursued them. In one theater, an audience watched them eat a meal on a stage. The highlight of their trip was an audience with King George II at Windsor Palace. He gave them “rich Garments laced with Gold,” which they wore for a group portrait. At the far right of the portrait stood the slight figure of a young man who would soon become known to the world as Attakullakulla, or Little Carpenter.1

Throughout his long, extraordinary life as a Cherokee statesman, Attakullakulla spoke often of his visit with the king. It was a source of personal prestige. Moreover, by informing him about the numbers and nature of the British, the visit helped prepare him for decades of imperial conflict in North America. “They are welcome to look upon me as a strange Creature,” he was once quoted saying about the mass of English spectators, “They see but one, and in return they give me Opportunity to look upon Thousands.”2

Attakullakulla travelled throughout North America within various war parties and diplomatic missions. Between the 1730s and 1770s, he regularly visited South Carolina and Virginia to negotiate treaties and settle disputes. In Williamsburg, he met with the governor and his council in the Palace and Capitol.3 Though often noted for his “small stature, slender, and delicate frame,” he was also recognized as a skilled diplomat and a powerful orator, with great influence over the Cherokee people.4

Like other Cherokee diplomats of the era, he spoke forcefully for his people about issues like trade, borders, and frontier violence. One 1755 newspaper reported him speaking at one gathering with “the Dignity and graceful Action of a Roman or Gracian [Greek] Orator, and with all their Ease and Eloquence.”5 To the Cherokee people, he was a white chief, which meant that he was responsible for diplomacy and trade rather than war. More than anyone else, he was responsible for opening trade between the Cherokee nation and Virginia. He likely died sometime in the early 1780s, leaving behind a powerful diplomatic legacy.

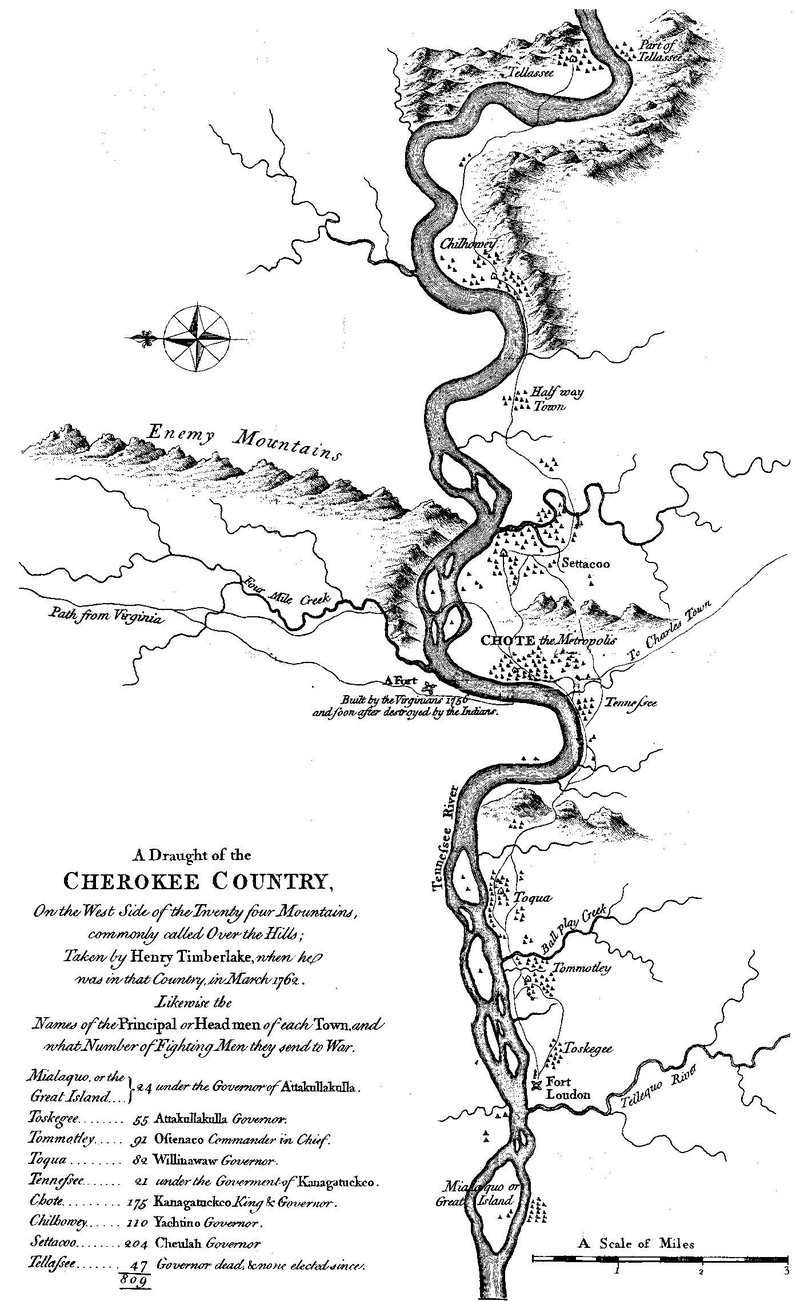

This 1765 map of the Cherokee Overhill towns demonstrates how Attakullakulla’s town Chota (at the center) was connected by paths to both Virginia and South Carolina, and by river to other important Overhill Cherokee towns. Henry Timberlake, The Memoirs of Lieutenant Henry Timberlake (1765).

Navigating Empires

We know little about Attakullakulla’s life before he reached England. He was from a collection of Cherokee settlements in what is now eastern Tennesseee called the Overhill towns. He was the youngest member of the 1730 Cherokee delegation in England. According to his later recollection, he had been the first of the group to agree to visit London. The others had accompanied him only so that he would “not go alone.”6 During the years after he returned from England, Attakullakulla was captured by Ottawa warriors, who were allied with the French empire. He was held in Canada for several years, where he met many French leaders, including the governor of New France. His travels gave him a better understanding of the rivalry between Britain and France than most of those born in the interior of North America.

This knowledge proved useful as the two colonial powers competed for Cherokee loyalty. Attakullakulla’s direct experience with these empires allowed him to occasionally play one against the other. As the Cherokee sought new trading partners, Attakullakulla considered re-aligning the Cherokee nation with France. Over time, though, he became a consistently pro-British voice in Cherokee councils—often putting himself in conflict with other factions. When British leaders accused him of working with France, he even led a war party to attack French-allied Native people to prove his loyalty to the British crown.7

English colonial leaders recorded many of Attakullakulla’s diplomatic speeches. But much could be lost in translation. For example, Attakullakulla consistently addressed the British colonists as a “Brother,” and framed the Cherokees and British colonists as “all children of the great King George.”8 Attakullakulla used familial language to assert his peoples’ equality with other colonial subjects and emphasize their mutual obligations. But these kinship metaphors meant different things in English society. In patriarchal England, a father was a figure of authority. In Cherokee society, where ancestry descended through the mother’s family, fatherhood conveyed respect, but not necessarily authority.9 The metaphor of fatherhood appealed to both groups, but for different reasons. Diplomacy sometimes relied on such misunderstandings and mistranslations.10

Diplomacy in Williamsburg

By the eighteenth century, cheap goods were being consumed around the globe. This consumer revolution affected how colonists engaged with Indigenous North Americans. Native people negotiated with settlers to secure goods, including guns and ammunition.11 But European traders sought to avoid competition. For example, the Cherokee struggled against a trade monopoly maintained by South Carolina in the early eighteenth century. Cherokee leaders frequently complained that the lack of competition allowed Carolinian traders to swindle them, inflate prices, and provide a poor selection of goods.12 Attakullakulla once complained, “Do what we may the white people will cheat us in Weights and Measures. What is it a Trader cannot do?”13

Attakullakulla worked for years to open new trading opportunities. In 1751, violence between colonists and the Cherokee caused South Carolina Governor James Glen to embargo the Cherokee trade. Attakullakulla visited Williamsburg to try to persuade the Virginians to trade with them. They initially rebuffed him. But the outbreak of war with France and its Native allies left Virginia vulnerable. In exchange for the Cherokee defending the colony’s western border, Virginia’s leaders agreed to build a fort among the Overhill settlements, where trade could be conducted.14 It took years of pressure to get Virginians to live up to their promises. Yet this remained one of Attakullakulla’s most important accomplishments: it opened commercial and diplomatic ties between Britain and the Overhill settlements, forcing colonizers to compete for Cherokee allegiance.

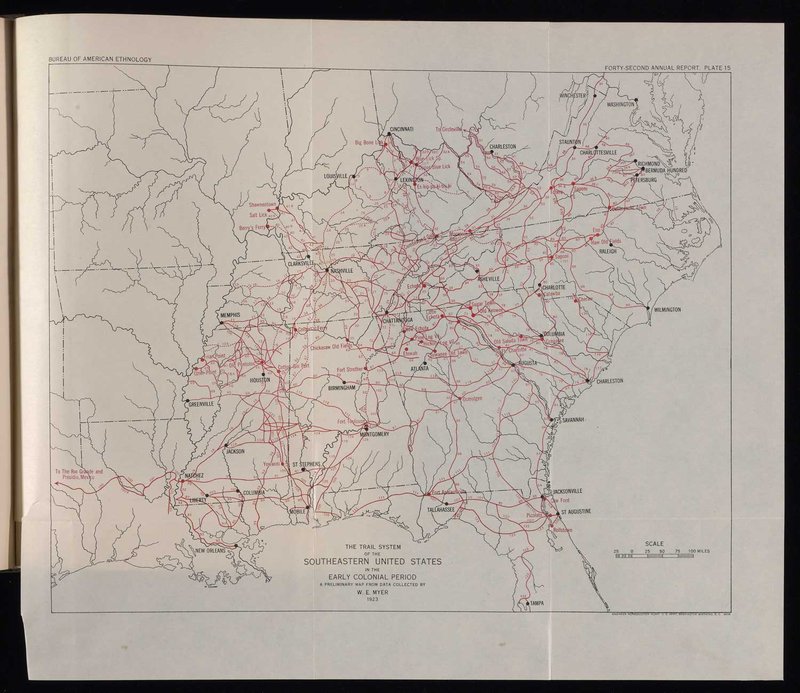

Attakullakulla and his party would have travelled from the Overhill towns to Williamsburg and back along trails developed through centuries of Indigenous peoples’ engineering and travel. William E. Myer, Indian trails of the Southeast (Smithsonian Institute, 1928). Courtesy Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Attakullakulla was one of many Indigenous visitors to Williamsburg over the years. He traveled to Virginia’s colonial capital many times over the years, often accompanied by a war chief such as Oconostota. It was a long journey from the Overhill settlements, taking a month of traveling through mountain passes and “small intricate paths” carved into the woods.15 Sometimes this was dangerous. More than once, unfriendly white settlers chased after Attakullakulla’s party as it left Williamsburg.16

Attakullakulla and his delegation likely sheltered in a temporary encampment while visiting Williamsburg. He would have been a visible presence in the city for five decades. One Williamsburg visitor recalled meeting him at the Cherokee encampment in 1777, where he “shook Hands & smoaked Part of a Pipe” with the delegation.17 After that meeting concluded, the Virginia Gazette reported that the delegation performed a dance on the Palace Green, which “agreeably entertained” numerous spectators.

Mural depicting the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals, which Attakullakulla helped to negotiate with settlers in 1775. Lucile Gulliver, Daniel Boone (Macmillan, 1916), 118.

Revolution and Death

Violence escalated between British colonists and Indigenous people in the 1760s and 1770s. This threatened relations between the Cherokee nation and the British empire. Attakullakulla helped to keep the Cherokees out of the Shawnee-Dunmore War in 1774. But he couldn’t prevent the colonists from sparking a war against the British empire, partly in pursuit of western lands. Attakullakulla’s son Dragging Canoe led a war of resistance from 1775 to 1794 to protect Cherokee land from encroaching settlers. In 1776, Virginia sent a military force that burned many of the Overhill towns.18

In 1777, Attakullakulla and other Cherokee leaders accepted defeat in Williamsburg. This would be Attakullakulla’s last act as a statesman. After lengthy negotiations, the Cherokee negotiators agreed to concede land to the colonists but refused to join the war against “their Father, King George.”19 Attakullakulla was probably present with the Cherokee delegation at a western fort on July 4, 1777, where colonists celebrated the first anniversary of American independence.20

The date of Attakullakulla’s death, like his birth, is unknown. He probably died in the early 1780s, around the same time as two other great Cherokee leaders, Oconostota and Old Tassel.21 Another generation, including Attakullakulla’s son (Dragging Canoe) and his niece (Nanyehi, or Nancy Ward), was already beginning to lead, although wih opposing views. They would face a new set of challenges with American independence. In the past, the presence of multiple empires in North America had allowed Attakullakulla to cleverly play colonizers against each other for Cherokee trade, loyalty, and protection. But now, the settlers were a united front. American independence would demolish the house built by the Little Carpenter.

Sources

Cover image courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

- Quoted in James C. Kelly, “Notable Persons in Cherokee History: Attakullakulla,” Journal of Cherokee Studies 3 (Winter 1978): 2, 4 (quote). He was at the time known as Okoonaka (meaning “White Owl”) and other variant spellings. The caption to the printed version of the portrait identifies him as “Ukwaneequa.” Alden T. Vaughan, Transatlantic encounters: American Indians in Britain, 1500-1776 (Cambridge University Press, 2006), 240; Miles P. Grier, “Staging the Cherokee Othello: An Imperial Economy of Indian Watching,” William and Mary Quarterly 73 (Jan. 2016): 88; Jace Weaver, “Shakespeare among the ‘Salvages’: The Bard in Red Atlantic Performance,” Theatre Journal 67 (Oct. 2015): 438–39.

- Kelly, “Notable Persons in Cherokee History,” 4, 10.

- On Attakullakulla’s visit to the Palace and Capitol in 1777, see William Q. Maxwell, “Governor's Palace Report, Block 20 Building 3A,” (1990) Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library; Stan Hoig, The Cherokees and Their Chiefs: In the Wake of Empire (University of Arkansas Press, 1998), 57.

- Vaughan, Transatlantic encounters, 137–39.

- “Charles-Town, July 31,” South-Carolina Gazette, July 31, 1755, p. 1.

- “Historical Relation of Facts Delivered by Ludovick Grant, Indian Trader, to His Excellency the Governor of South Carolina,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 10 (Jan. 1909): 66–68; Kelly, “Notable Persons in Cherokee History,” 3.

- Kelly, “Notable Persons in Cherokee History,” 6–7, 9, 19; Gregory Evans Dowd, “The Panic of 1751: The Significance of Rumors on the South Carolina-Cherokee Frontier,” William and Mary Quarterly 53 (July 1996): 538.

- See for example, Williamsburg heading, Virginia Gazette (Hunter), Aug. 16, 1751, p. 2, link; Kelly, “Notable Persons in Cherokee History,” 10.

- Theda Perdue, Cherokee Women: Gender and Culture Change, 1700–1835 (Lincoln: 1998), 42–43, 48; Gregory D. Smithers, “‘Our Hands and Hearts are Joined Together’: Friendship, Colonialism, and the Cherokee People in Early America,” Journal of Social History 50 (Summer 2017): 614, 617.

- Richard White, “Creative Misunderstandings and New Understandings,” William and Mary Quarterly 63 (Jan. 2006): 9–14.

- John K. Thornton, A Cultural History of the Atlantic World, 1250–1820 (Cambridge University Press, 2012), ch. 9.

- Kelly, “Notable Persons in Cherokee History,” 3

- Quoted in Samuel Cole Williams, Dawn of Tennessee Valley and Tennessee History (Watauga Press, 1937), 132n20, link.

- Kelly, “Notable Persons in Cherokee History,” 11.

- Susan Kern, The Jeffersons at Shadwell (Yale University Press: 2010), 194–97. One very careful expense report documents one such trip accompanying Overhill Cherokee diplomats. See Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts, vol. 1 (R. F. Walker, 1875), 244, link.

- Kelly, “Notable Persons in Cherokee History,” 18; Jay Donis, “‘No man shall suffer for the murder of a Savage’: The Augusta Boys and the Virginia and Pennsylvania Frontiers,” Pennsylvania History 86 no. 1 (Winter 2019): 38–48.

- May 30, 1777 entry in “Journal of Ebenezer Hazard’s Journey to the South, 1777,” in Mary Goodwin, “The Capitol: Second Building, 1747-1832,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library, 55-a. Thomas Jefferson later remembered that “before the revolution,” Native diplomats “were in the habit of coming often, & [in] great numbers to the seat of our government.” “To John Adams from Thomas Jefferson, 11 June 1812,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5806.

- Kelly, “Notable Persons in Cherokee History,” 26.

- Charles Robertson to Richard Caswell, April 27, 1777, in The State Records of North Carolina, 1776-1790, ed. Watler Clark, vol. 11 (M. I. & J. C. Stewart, 1895), 459.

- Archibald Henderson, “The Treaty of Long Island of Holston, July, 1777,” North Carolina Historical Review 8 (Jan. 1931): 66.

- Kelly, “Notable Persons in Cherokee History,” 27.