Robert Mursh

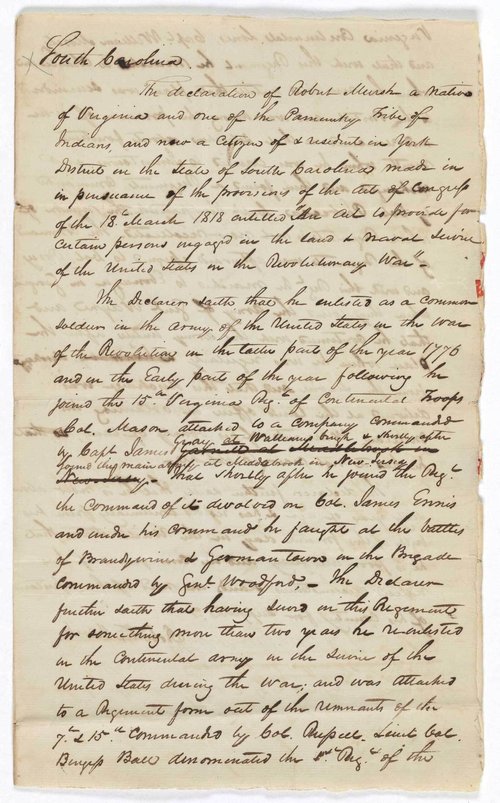

Robert Mursh (sometimes spelled Marsh or Mush) left few records about his life. Most of what we know about his life comes from an 1818 pension application, seeking benefits for his service in the American Revolutionary War. As a member of the Pamunkey tribe, Brafferton Indian School alumnus, and Baptist missionary, Mursh was not the ordinary pension applicant.

His application, which was approved, offers insight into his life and uncommon story. Yet it also raises many broader questions. How did Indigenous people navigate the rapidly changing world around them? How did white Americans attempt to acculturate Native people? Mursh’s life was unusual, but his story illuminates broader questions about the tenuous nature of allegiance in revolutionary America.

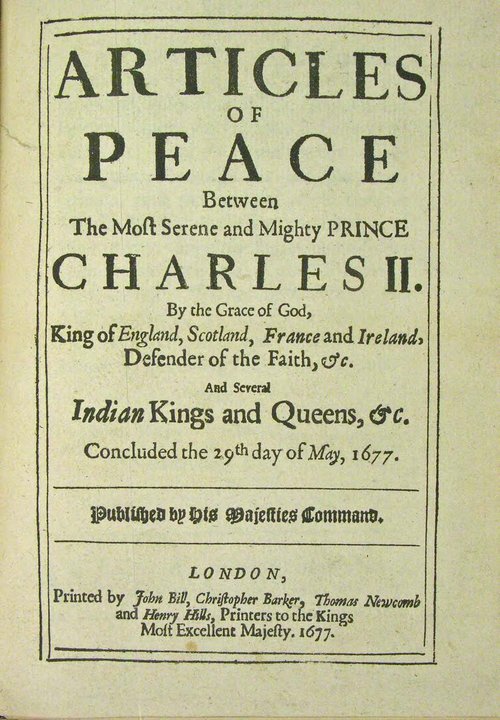

Treaty of Middle Plantation (1677)

Found on https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/articles-of-peace-1677/

A People of the Chesapeake

Mursh was born in 1758 into a tribe that had long been a powerful force in the Chesapeake region of what is now known as Virginia. The Pamunkey Chiefdom formerly held territory along the upper James and York Rivers, and comprised dozens of local groups. During the late sixteenth century, the Pamunkey Chief Powhatan expanded the paramount chiefdom to include all the lands and peoples of the lower James and York basins. By the end of the seventeenth century, however, colonization and violence had forced the Pamunkey to lead a remnant population, ceding much of their lands and power to the colony of Virginia.1

As part of the Treaty of Middle Plantation (1677), the Pamunkey were guaranteed sovereignty over their lands in exchange for “fidelity” to the colony, which would be maintained, in part, through an annual tribute. Between 1708 and 1710, Virginia’s Lieutenant Governor, Alexander Spotswood, offered to remit the annual tribute if one or two student “hostages” were sent each year. Unlike the modern notion, these boys were not prisoners, but closer to diplomats, whose presence in the colonial capital was a signifier of both the Pamunkey and Virginia’s continued commitment to their treaty. Furthermore, the students would be “educated and initiated in the principles of Christianity” at the College of William and Mary, something some Virginians had high hopes would prove useful in the future.2 Mursh would be one such student hostage in his youth.

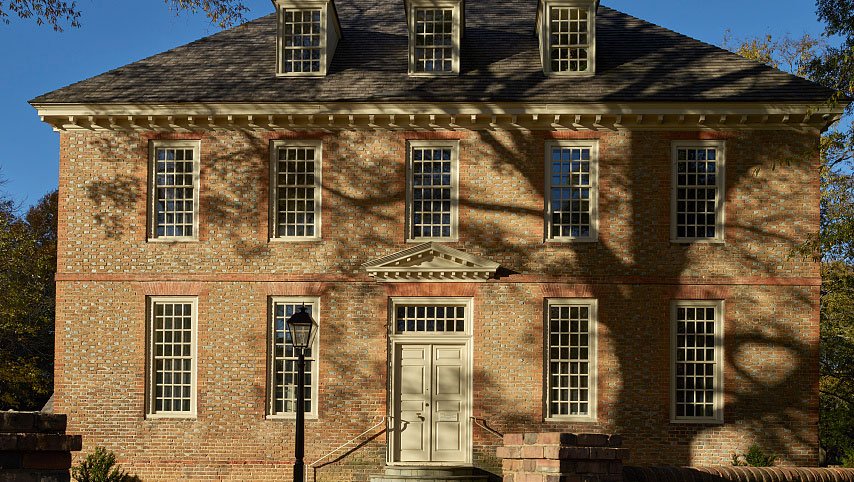

Image of the Brafferton School

Studying at the Brafferton

By the time Mursh was sent to Williamsburg, the practice of sending young boys to be educated at William and Mary had been consistently taking place for decades. The Brafferton Indian School was constructed on campus by 1723, and it was where Mursh would have lived and been instructed. While at the Brafferton School, Mursh would have also attended Bruton Parish Church, further cementing his Christian education. As he lived in Williamsburg, Mursh would have also been taught the English language and European norms, with the hopes he would someday act as a go-between for the colonists with Native Americans.3

By the time Mursh attended the Brafferton School, the Pamunkey had been consistently sending more boys for education at the Brafferton School than other tribes. What students like Mursh thought as they began their education is unknown. Mursh, nonetheless, came to Williamsburg during a time of rapid change. As he arrived at the Brafferton in 1769, the ongoing colonial crisis filled the air with revolutionary ideals. It’s certainly likely Mursh would have been exposed to such ideas, and he may have become involved in discussions surrounding colonial autonomy, the rights of colonists, and the place of government. Mursh’s education lasted until at least 1774, and it’s unknown exactly how his time in revolutionary Williamsburg influenced him. What we do know, however, is he would soon join the Patriot cause.4

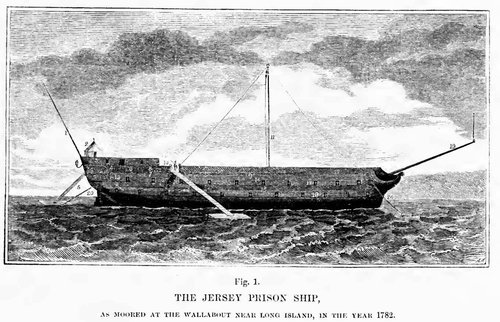

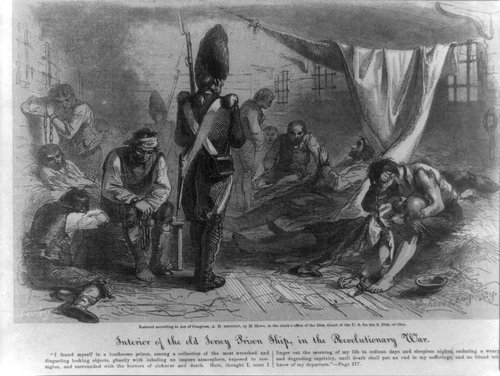

The Old Jersey Prison Ship

A Native Revolutionary

In 1776, Mursh joined the American cause against Britain. He enlisted in the 15th Virginia Regiment. Unlike many soldiers, Mursh served for nearly the entirety of the war. Mursh was first sent to Middlebrook, New Jersey.5 While in the region, Mursh participated in some of the Revolutionary War’s most famous battles. On September 11, 1777, he took part in the Battle of Brandywine, the second longest battle of the war. The next month, Mursh fought in the Battle of Germantown. By the end of the year, Mursh was wintering in Valley Forge in Washington’s army, an infamously difficult time for the American forces, as they suffered from lack of resources and bitter cold. When fighting resumed the next year, Mursh took part in the Battle of Monmouth on June 28, 1778.6

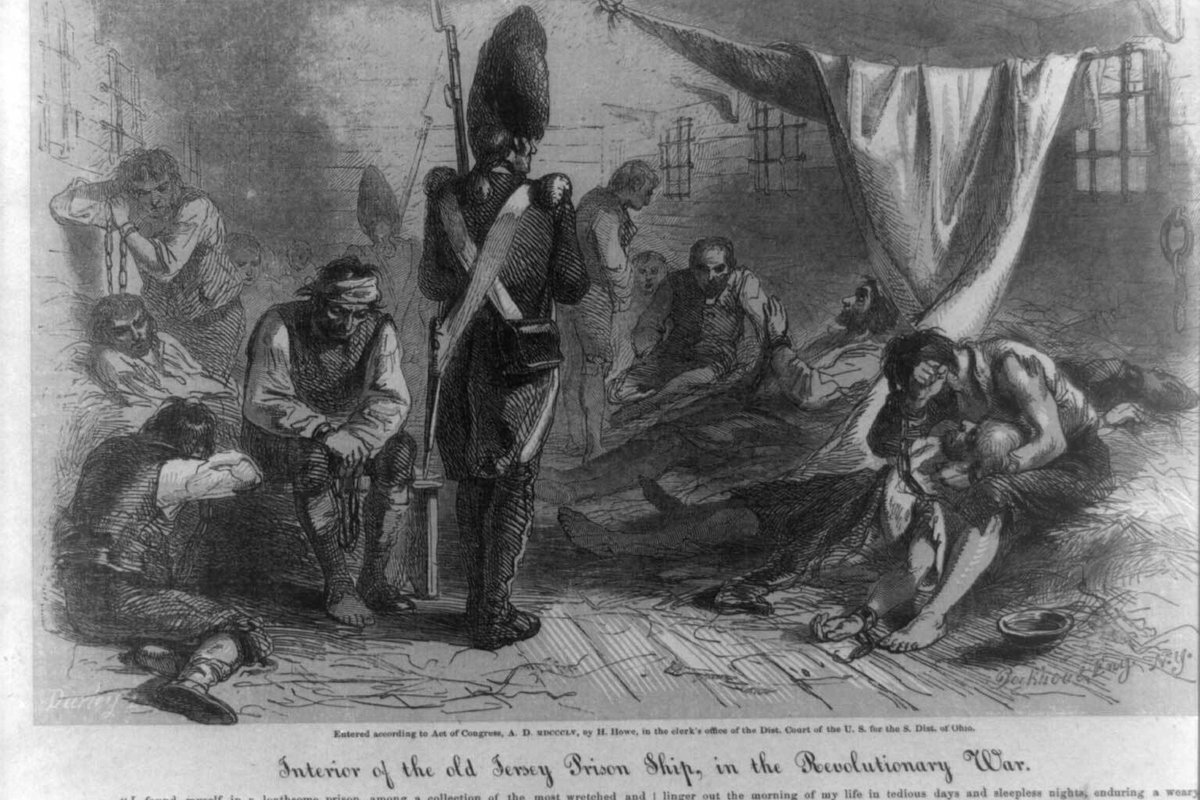

By 1779, Mursh went south to assist Americans defending Charleston against a British siege. When the city eventually fell, Mursh and almost 5,500 soldiers became prisoners of war. He spent the next fourteen months aboard prison barges in the Charleston harbor. Conditions on these ships were notoriously dire. By the time Mursh was forced aboard one, many Americans had heard the horror stories of British prison ships in other areas. Overcrowding, little food, barely any medical care, and scores of dead were just some of the things Mursh would have certainly encountered. Many prisoners of war were so scared of these conditions they defected to the British rather than face them.7

Interior of the Old Jersey Prison Ship

Mursh and other soldiers were freed in 1781 as part of a prisoner exchange on Jamestown Island. He immediately reenlisted and joined the army’s preparations to march on Yorktown. He was present for the surrender of General Charles Cornwallis in October. His military service, however, didn’t end there. After Yorktown, Mursh accompanied forces as they made their way south once more. He fought occasional skirmishes with British-allied Choctaws, Upper Creeks, British Regulars, and Loyalists, as American forces attempted to retake Charleston and Savannah. In 1782, with both cities retaken, Mursh’s enlistment came to an end. He was discharged from service.8

Why did Mursh serve on the American side of the war? It’s difficult to know. His time as a student at the Brafferton, especially during the latter stages of the Revolution, could have influenced his opinions of Virginians. The Pamunkey people’s relatively close ties to Virginians, which included protections for their land and sovereignty, could have meant he was raised in an environment with more favorable views towards colonists than other Native peoples. It is also possible Mursh, like many others, simply made the difficult decision to join the side they thought would serve their interests. Whatever his reason, Mursh’s post-war life shows a man who increasingly embraced some aspects of Anglo-American culture, while still holding onto aspects of his Pamunkey and Indigenous identity.

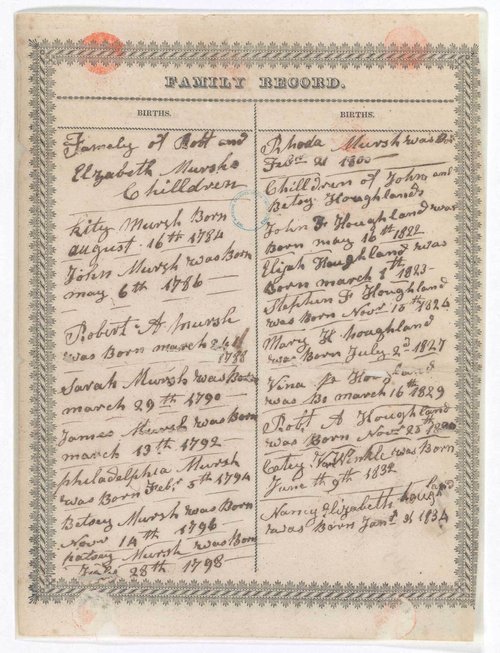

Robert Mursh’s Family Record, Revolutionary War Pension & Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives

Post-War Life

After the war, Mursh returned to the Pamunkey people. In 1783, he married Elizabeth, a fellow Pamunkey person, according to their tribe’s traditions. Their decision to do so, even after Mursh had received a Christian education, illustrates a commitment to Pamunkey culture. At the same time, however, Mursh became increasingly involved in the burgeoning Baptist movement among Tidewater Native people. By the 1790s, the Baptist faith would become particularly popular among the region’s indigenous people.9

Robert and Elizabeth became active members of the Lower College Baptist Church. Established in 1791, the church likely became a major part of their lives. In 1797, the two were remarried according to Christian traditions. The exact reason for the second marriage is unknown, but Mursh became a Baptist preacher the next year. To be recognized as a preacher, he may have needed to conform his marriage to Christian norms.10

After almost a decade at the church, however, Mursh moved his family to the Catawba nation, within South Carolina. Mursh may have been invited there by fellow Brafferton alumnus and veteran John Nettles, who lived in the region and worked as a Baptist missionary. In 1800, the Murshes settled into the Lancaster District of the Catawba nation, and soon after welcomed their ninth child.11

Robert Mursh Pension Letter, Revolutionary War Pension & Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives

By 1806, Mursh had become an official Baptist missionary in the Catawba nation, working alongside Nettles and John Rooker. Rooker had been among the Catawba since 1793, when the Charleston Baptist Association sent him to begin missionary work. The three men established the new Hopewell Baptist Church. Sometime between 1806 and 1807, Mursh moved his family to the York District, and became members of the Flint Hill Baptist Church, where he continued to work closely with Nettles and Rooker as an assistant preacher.12

The Mursh family seemingly assimilated into Catawba culture quite nicely. By the 1810s and 1820s, the extended Mursh family included children and grandchildren scattered across the nation. Genealogical records show many members of Mursh’s family married into the Catawba, and their descendants can still be found among the tribe today.13

Conclusion

How did the Mursh family think of themselves? As Indigenous? As American? As both? Neither? Mursh seems to have embraced Anglo-American culture over time. A white neighbor of his described Mursh as having “adopted in full the dress and habits of the white man” when he had last seen him in 1827. The Mursh household, however, shows a mix of Indigenous and non-Native cultures. Archeological evidence from their home has shown the household’s women may have been involved in traditional pottery manufacturing, selling their products at local markets. The household also included a mix of manufactured items and iron forged kitchenware and agricultural equipment.14

We know much about Mursh’s life, but little about how he made his choices. We can see a Pamunkey Native American who clearly embraced, and even fought for, American values. But we also know he chose to live among Native peoples, indicating he likely still held some connections to the communities around him. From a Pamunkey child to Brafferton student, from a soldier to a preacher, Mursh lived a life like few others. His life shows us that Native identity in early America was complex and ever changing, as people made different choices for themselves, their families, and community.

Sources

- Buck Woodard, “Students of the Brafferton Indian School,” in Building the Brafferton: The Founding, Funding, and Legacy of America’s Indian School, Danielle Moretti-Langholtz and Buck Woodard, eds. (Williamsburg, Va: Muscarelle Museum of Art, 2019), 130.

- Julia M. Gossard and Holly N. S. White, eds., Engaging Children in Vast Early America (Routledge, 2024), 108; Woodard, “Students of the Brafferton Indian School,” 130.

- Martin D. Gallivan, The Powhatan Landscape: An Archaeological History of the Algonquian Chesapeake (University Press of Florida, 2016).

- Hatfield, “Spanish Colonization Literature, Powhatan Geographies, and English Perceptions of Tsenacommacah/Virginia,” 250; Ethan A. Schmidt, “Cockacoeske, Weroansqua of the Pamunkeys, and Indian Resistance in Seventeenth-Century Virginia,” American Indian Quarterly 36, No. 3 (Summer 2012): 309–10; James Axtell, The Invasion Within: The Contest of Cultures in Colonial North America (Oxford University Press, 1985), Ch. 8; R. A. Brock, The Official Letters of Alexander Spotswood, Lieutenant-Governor of the Colony of Virginia, 1710-1722, vol. 1, (Virginia Historical Society, 1882), 134, 121, 108

- Woodard, “Students of the Brafferton Indian School,” 131; Robert Mursh (Pamunkey), M804 Roll 1797 W.8416, Revolutionary War Pension Petition, 1818, National Archives, Washington, D.C..

- Woodard, “Students of the Brafferton Indian School,” 131; Robert Mursh (Pamunkey), M804 Roll 1797 W.8416, Revolutionary War Pension Petition, 1818, National Archives, Washington, D.C..

- Woodard, “Students of the Brafferton Indian School,” 131; Philip Ranlet, “In the Hands of the British: The Treatment of American POWs during the War of Independence,” The Historian 62 (no. 4, Summer 2000): 731-758.

- Woodard, “Students of the Brafferton Indian School,” 131–32.

- Woodard, “Students of the Brafferton Indian School,” 132.

- Woodard, “Students of the Brafferton Indian School,” 132.

- Woodard, “Students of the Brafferton Indian School,” 133.

- Woodard, “Students of the Brafferton Indian School,” 133.

- Woodard, “Students of the Brafferton Indian School,”133; Ian Watson, Catawba Indian Genealogy (State University of New York at Geneseo, 1995), 70–93.

- Woodard, “Students of the Brafferton Indian School,” 133; Steve Davis and Brett Riggs, “Archaeology in the Old Catawba Nation (The Catawba Project) (Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2004): 15-37.