What did the Founders mean by “Freedom of the Press”?

The founding generation’s understanding of a free press has a long history, partly inherited from English law. But that doesn’t mean that England always had a free press.

Starting in the year 1534 England, wrote into its laws what would become known as the Licensing Laws. These laws demanded that all presses in England be licensed. Rev. Joseph Glover of Massachusetts brought the first press into British North America in the year 1639. Rev. Glover traveled to England to buy a press and hire a printer named Stephen Daye. Unfortunately, Joseph Glover died on the voyage back to the colonies. The printer that he hired, Stephen Daye, secured the press and was granted the right by the elders of Massachusetts to run it. The American printing industry was born.

In the year of 1644, the first real push against the Licensing Laws came from John Milton in his pamphlet Areopagitica; a speech of Mr. John Milton for the liberty of unlicenc'd printing, to the Parliament of England. In 1694, the Licensing Laws were repealed—but not without restriction. The Seditious Libel Law came into play. This law stated that it was a crime to publish anything disrespectful of the King, state, church or their officers. In 1734, a printer named John Peter Zenger of New York, challenged that law when he was brought up on charges of sedition in 1734, arguing that the seditious material he had published was truthful. Zenger won his case.

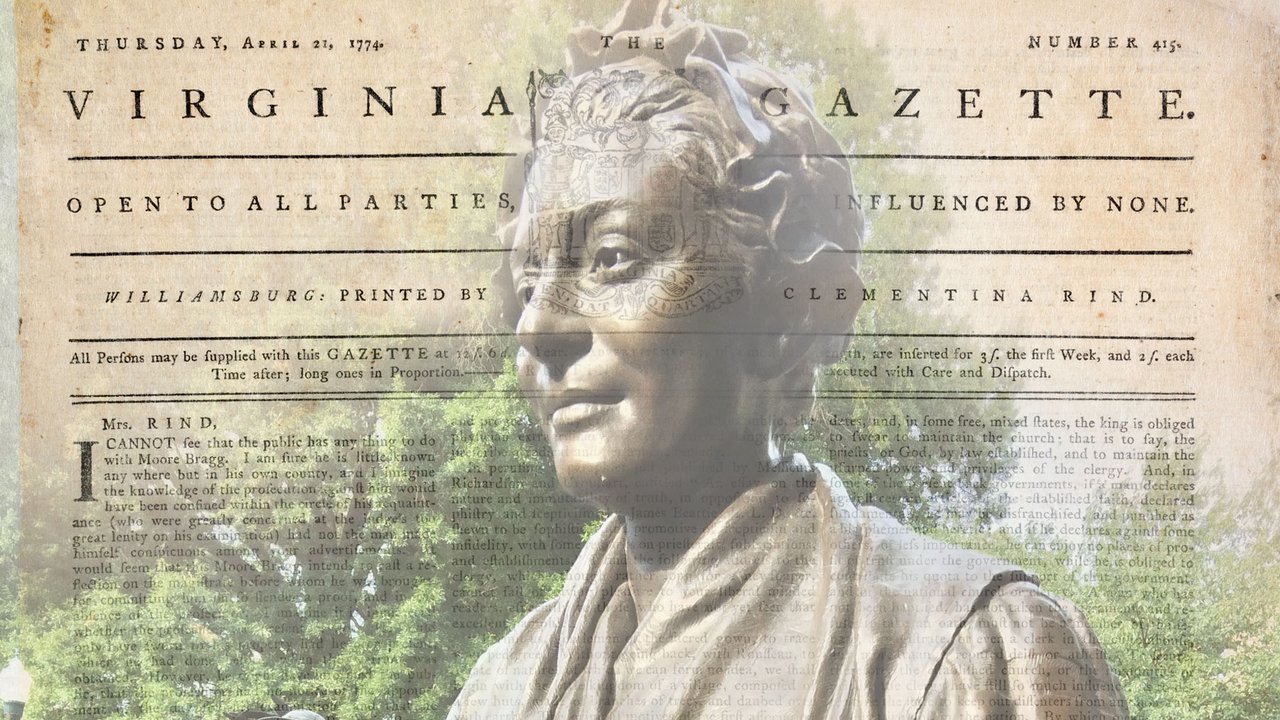

Visit the printing office, or look for Nation Builder Clementina Rind to learn more about how the freedom of the press thrived in 18th-century Williamsburg

In 1683, a Virginia printer named William Nuthead moved to Jamestown and attempted to become her first printer. The Royal Governor Sir Thomas Culpeper and his council took offense to this and wrote to the King for guidance. King Charles II responded, specifically prohibiting printing in Virginia. This allowed Maryland to have an operating printing office before Virginia. Nuthead moved and set up his shop in St. Mary’s City. Virginia had to wait 47 more years before it saw its first real printer. In 1730 William Parks, from Maryland, moved to Williamsburg to set up his printing office. In June 1732, Parks was granted the first commission as “Printer to the Colony of Virginia” and by the 1760s, Virginia had two operating printing offices.

Things started to heat up in the colonies’ presses throughout the 1760s and 1770s. Printers like John Hunter Holt challenged the seditious libel law repeatedly, and dissented from government decisions. In September of 1775, Holt used language referring to the British navy as pirates. Dunmore wrote a letter telling Holt to be fair in his reporting—or else. The very next issue on September 27, Holt poked fun of Dunmore and his family. For Dunmore that was the last straw. He sent out a party of marines to seize Holt. Holt hid and the marines seized his press, types, paper, and two workers. The governor thought that he would use the equipment on board his ship to print his own newspaper and bring balance back to the press.1

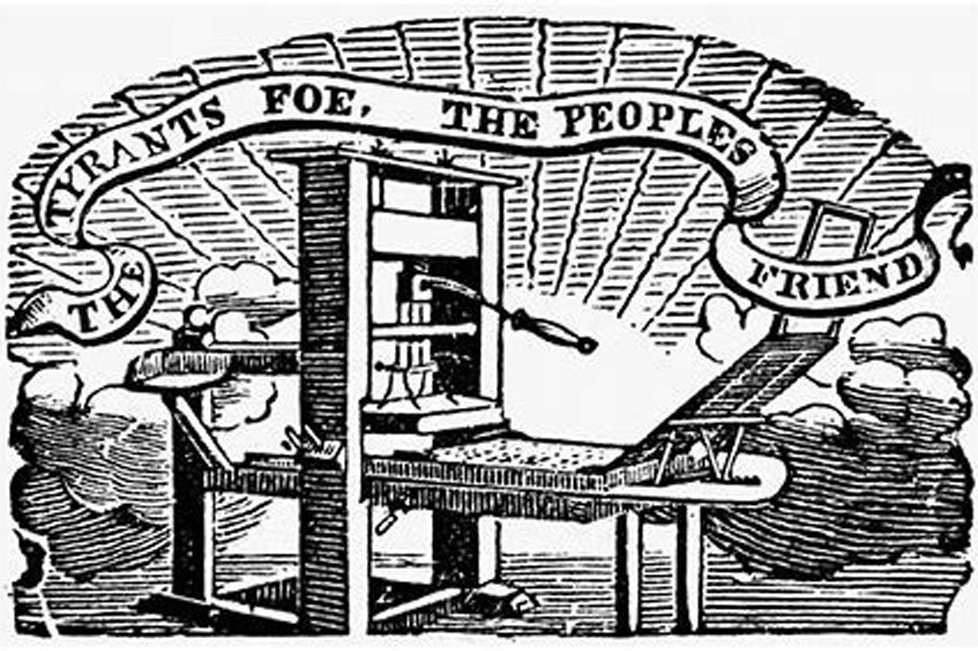

Printer

In an age before TV, radio, and the internet, the printed word was the primary means of long-distance mass communication. Watch and learn as printers set type and use reproduction printing presses to manufacture colonial newspapers, political notices, pamphlets, and books.

Clementina Rind’s Revolutionary Press

Not long after her husband’s funeral, Clementina Rind sat down at his desk, now hers, to write. During the thirteen months following William’s death, she deftly navigated these challenging circumstances.

Sources

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie), Oct. 17, 1775.