Raleigh Tavern

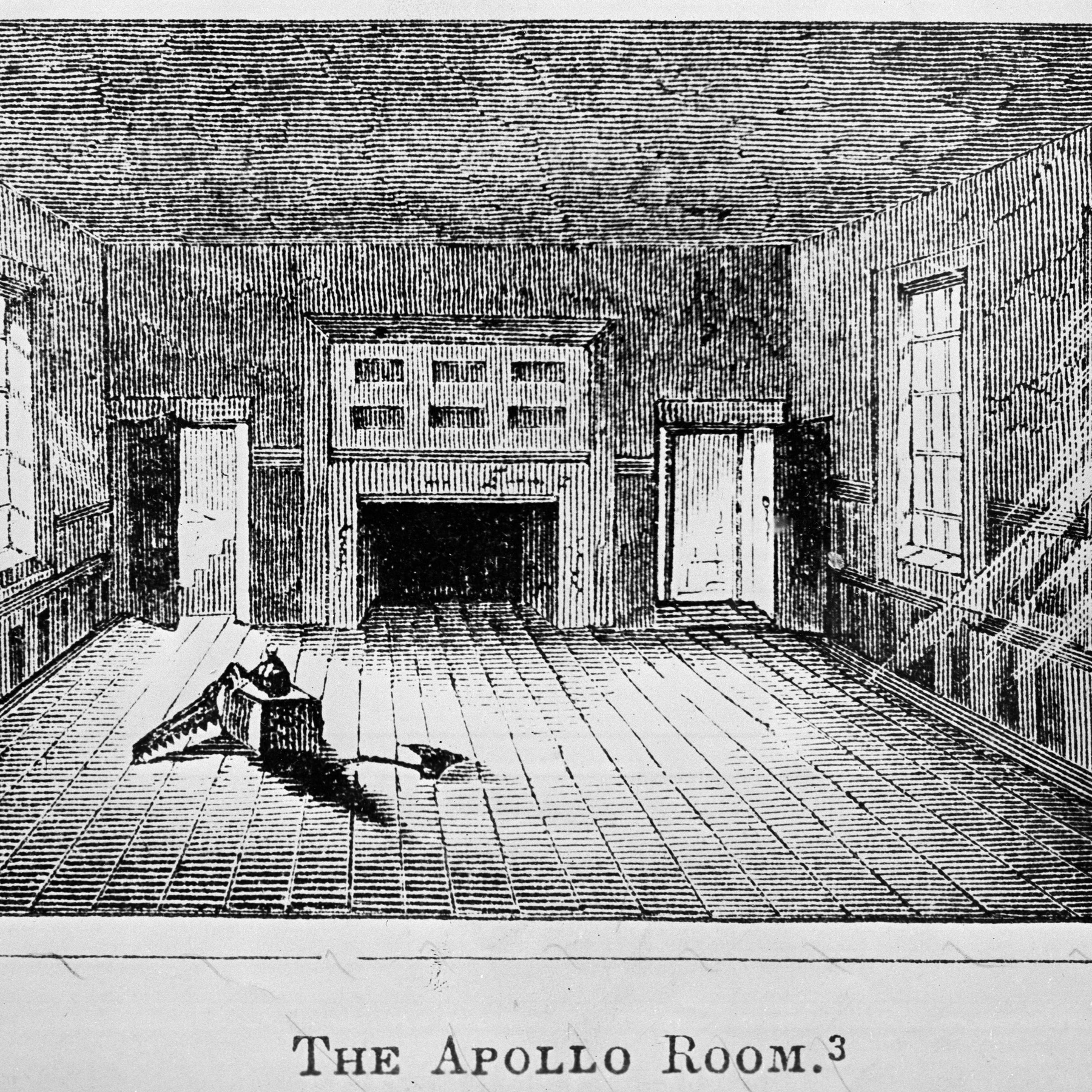

The Raleigh Tavern was the stage for much of Virginia’s revolutionary drama. Some of the American Revolution’s most fateful conversations happened in the building’s Apollo Room. As you tour this site, you will learn about the extraordinary events that took place here, as well as about the rhythms of life inside an 18th-century tavern. Established around 1717, the Raleigh Tavern was a mainstay of Williamsburg’s Duke of Gloucester Street.

Tavernkeepers

Those who managed the Raleigh included Henry Bowcock, Henry Wetherburn, Alexander Finnie, William Trebell, Anthony Hay, and James Southall. They grew the Raleigh into a large, respectable business. Southall, who was a leading local Patriot, helped to promote the tavern as a space for revolutionary agitation.4

Tavern keepers’ wives played an important role in the business. In addition to running their own household, they likely supervised the servants and enslaved people who worked in the tavern’s kitchen and bedchambers. After Henry Bowcock died in 1730, his widow Mary Bowcock briefly operated the tavern on her own account.5

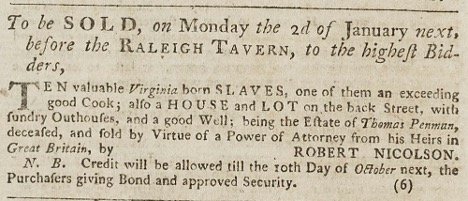

The porch and steps of the Raleigh Tavern were often used for auctions in early Williamsburg. In this 1774 Virginia Gazette advertisement, tailor Robert Nicolson arranged for an auction of ten enslaved people “before the Raleigh Tavern.” Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), November 24, 1774, page 2. Click the image to see it in context.

Enslaved People at the Raleigh Tavern

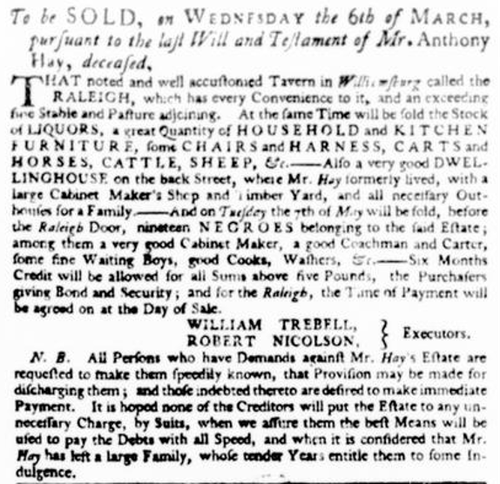

An advertisement in a 1771 issue of the Virginia Gazette describes how 19 enslaved people belonging to the estate of Anthony Hay would be “sold, before the Raleigh Door.” Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Jan. 17, 1771, p. 3.

Though enslaved people were not allowed to be served at the Raleigh Tavern, their skilled labor kept it running. They mucked the stables, tended the garden, hauled supplies, cleaned rooms, washed linens, played music, and cooked, baked, and served food. In 1783, a German visitor to Williamsburg named Johann David Schoepf recalled visiting a tavern, probably the Raleigh, and meeting “Black cooks, butlers, [and] chamber-maids” who “made their bows with much dignity and modesty.” Working at the center of Williamsburg’s social scene, the Raleigh’s enslaved people encountered a diverse range of people. According to Schoepf, after the Revolutionary War’s conclusion, the enslaved tavern workers “still spoke with enthusiasm” about the “politeness and gallantry of the French officers” whom they had hosted.6

While enslaved people lived and worked at the Raleigh Tavern throughout its existence, surviving historical records tell us the most about those people who were enslaved by Anthony Hay. In 1769, Hay’s household at the Raleigh sent three enslaved boys named Jerry, Joseph, and Dick to be educated at the Bray School. When Hay died in 1770, an inventory of his property listed twenty enslaved people: Lucy, Peggy, Ben, Lucy, Jimmy, Jenny, Caesar, Gaby, Rachel, Rippon, Jerry, Wiltshire, Sarah, Mary, Will, Tom, Kate, Betty, Nancy, and Edmund. The executors of Hay’s estate organized a sale “before the Raleigh Door” of nineteen enslaved people. The estate sold only one enslaved person, a coachman and carter named Will, to the Raleigh’s new owner James Southall.7 The others were sold to new enslavers.

.

Visitors

The Raleigh Tavern was a one-stop shop for visitors to Williamsburg. It provided guests with lodging, food, drink, entertainment, and a stable for their horses. Those staying overnight at the Raleigh Tavern slept in one of its dozens of beds, or on the floor, usually alongside other lodgers.8 Visitors had plenty of ways to entertain themselves. They could play cards, billiards, bowling games, chess, and more.9

And, of course, they could drink alcohol, including wine, rum, porter, ale, and punch.10 The punch served by Henry Wetherburn at the Raleigh was well-loved. It was, at least, valuable enough to William Randolph of Tuckahoe that he once conveyed a two-hundred-acre tract of land to Peter Jefferson (father of Thomas Jefferson) in exchange for “Wetherburn's biggest bowl of arrack punch.”11

Entertainments

The Raleigh Tavern often served as a public space for celebrations and commemorations. In 1771, for example, Governor Dunmore gave a ball at the Palace to celebrate King George III’s accession to the throne. For those not invited to the Palace, Dunmore directed that the Raleigh Tavern be “opened for the Entertainment of such as might incline to spend the Evening there.” The Virginia Gazette reported that “Plenty of Liquor was given to the Populace.”12

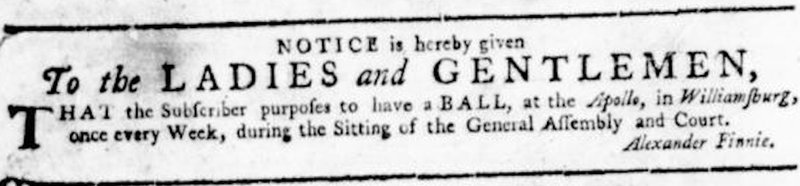

In 1752 Alexander Finnie, who then kept the Raleigh Tavern, advertised plans to hold a “Ball, at the Apollo” room once a week “during the Sitting of the General Assembly and Court.” Virginia Gazette (Hunter), Feb. 27, 1752, p. 4.

During the busy weeks when the courts and legislature were in session, the Raleigh Tavern hosted regular balls. During one such social season, a twenty-year-old Thomas Jefferson wrote to a friend feeling “melancholy” the morning after a ball at the Raleigh. As “merry” as he had been “dancing with Belinda in the Apollo,” he now felt “wretched” for having embarrassed himself in conversation: “a few broken sentences, uttered in great disorder, and interrupted with pauses of uncommon length, were the too visible marks of my strange confusion.” Since balls were important occasions for members of the Virginia gentry to display their social refinement, young Jefferson’s mortification is understandable.

The Raleigh Tavern also hosted many private club meetings. George Washington, among others, attended “Club” at the Raleigh.13 William & Mary students met in secret societies at the Raleigh, including a group called the F. H. C., or “Flat Hat Club.”14 In 1776, a group of William & Mary students founded the fraternity Phi Beta Kappa, making it the oldest academic honor society in the United States. The society’s records indicate that they thereafter planned anniversary meetings at the Raleigh Tavern, indicating that the society was likely founded there.15

Bayonets at a Birthday Party

When you picture an “elegant” celebration in eighteenth-century Williamsburg, you might imagine fine clothing, hearty food and drink, and entertainment of music and dancing. But what about cannons?

Explore how Williamsburg first celebrated George Washington’s birthday.

Afterlife

As Virginia’s capital moved to Richmond in 1780, the Raleigh Tavern remained an important part of Williamsburg’s social life. One visitor in 1796 described the Raleigh Tavern as almost a college bar, a place where “the students gave their balls—or met to play billiards.”16 Even as it became less important to Virginia’s politics, it was long remembered as a revolutionary landmark. When the Marquis de Lafayette returned to Williamsburg during his 1824 tour of the United States, he dined at the Raleigh Tavern with many of Virginia’s leading citizens.17

In 1848, the journalist and historian Benson Lossing visited the Raleigh Tavern just as its interior was being remodeled. As he watched carpenters tearing down the old Apollo Room, he later wrote that he felt that he was witnessing an act of “desecration,” since the Raleigh Tavern was to Virginia “what Faneuil Hall is to Massachusetts,” a place where radical ideas first began to coalesce into revolutionary action.18 The Raleigh Tavern burned down in December 1859.19

Reconstructing the Raleigh

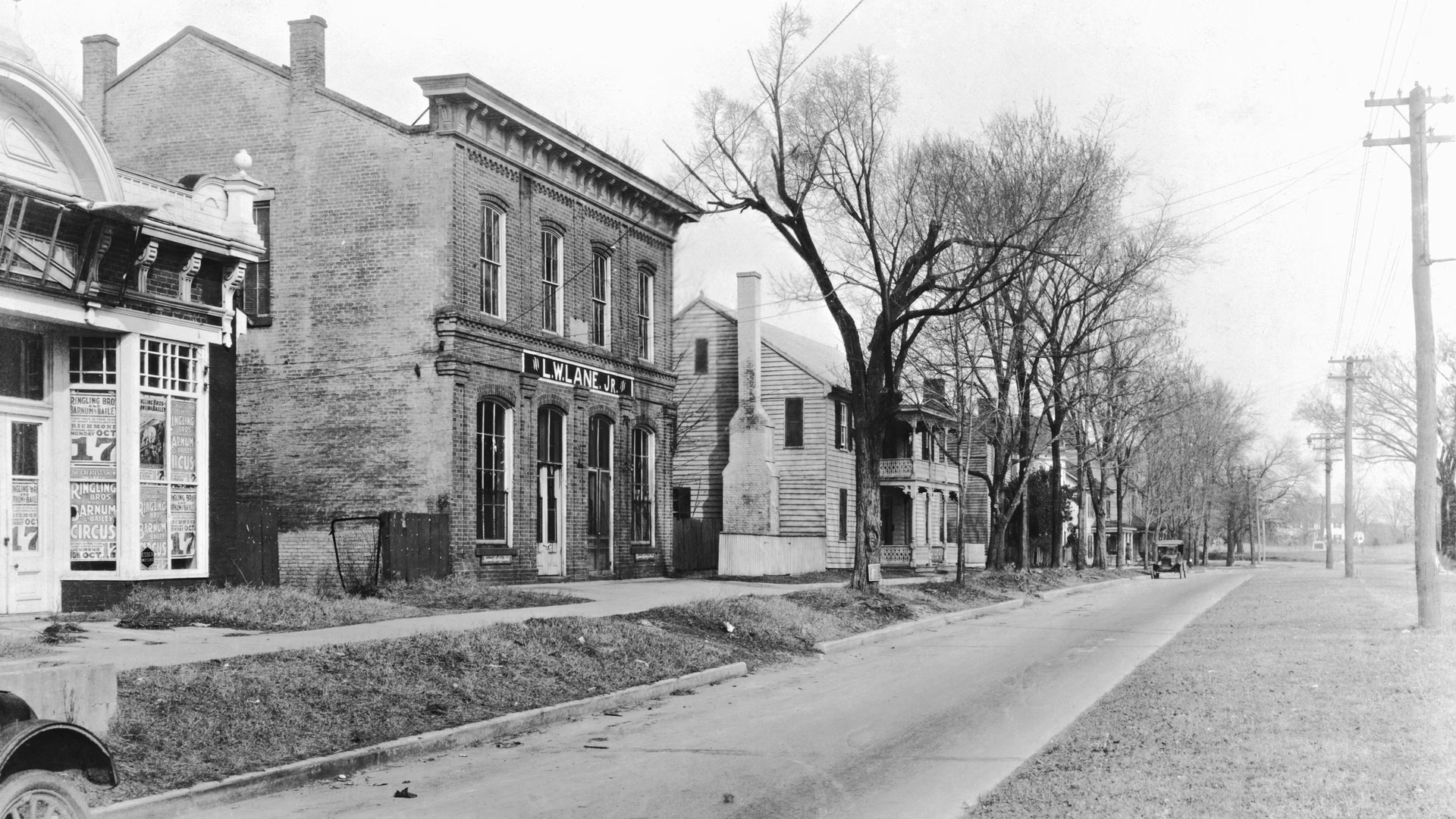

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Colonial Williamsburg purchased the land, excavated it, and reconstructed the building. When work started in 1927, the site of the Raleigh Tavern was occupied by two modern stores.

Reproducing Sir Walter Raleigh

In 2017, a lead bust of Sir Walter Raleigh was removed from the pediment above the front door of the Raleigh Tavern and conservators addressed the sculpture's corrosion and structural damage issues.

Raleigh Tavern Today

Over the years, the Raleigh Tavern has been thoroughly updated to reflect emerging research. Today it is a centerpiece of Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area. Millions of people have come to the Raleigh Tavern to learn not only about the revolutionary events that took place within its walls, but also the stories of ordinary people eating, drinking, sleeping, and socializing in a colonial tavern.

Raleigh Tavern Webcam

View from the King’s Arms Tavern looking north toward the Raleigh Tavern on Duke of Gloucester Street in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area.

Sources

- John Pendleton Kennedy, ed., Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1766-1769 (Richmond: 1906), xxix–xlii, link.

- Robert L. Scribner, ed., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, vol. 1: Forming Thunderclouds and the First Convention, 1763–1774 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1973), 90–92.

- John Pendleton Kennedy, ed., Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia 1773–1776 including the records of the Committee of correspondence (Richmond: E. Waddey Co., 1905), 132, link; Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), May 26, 1774, p. 3, link.

- Patricia Ann Gibbs, “Taverns in Tidewater Virginia, 1700-1774,” (Ph.D. diss., College of William & Mary, 1968), 197.

- Mark R. Wenger, “The Construction of Raleigh Tavern: A Brief Report on its Eighteenth-Century Development,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library (1990); Gibbs, “Taverns in Tidewater Virginia,” 45, 142–43.

- Johann David Schoepf, Travels in the Confederation [1783–1784], trans. Alfred J. Morrison (Philadelphia: William J. Campbell, 1911), 81.

- “Enslaving Virginia,” Colonial Williamsburg research report (1998), 626–33.

- Anthony Hay’s 1771 estate inventory listed “32 bedsteads, 25 beds, 1 bason stand, 1 matt, 3 mattrasses, 35 counterpanes, 40 pairs sheets, 37 pillow cases, 122 china plates and 37 table cloths and 26 napkins,” which indicates the number of beds available at the Raleigh Tavern at that time. See “A Study of Taverns of Virginia in the Eighteenth-Century with Special Emphasis on Taverns of Williamsburg,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library (1990), 13.

- “A Study of Taverns of Virginia in the Eighteenth-Century with Special Emphasis on Taverns of Williamsburg,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library (1990), 23.

- Gibbs, “Taverns in Tidewater Virginia,” 79.

- Mary E. McWilliams, “Raleigh Tavern Historical Report, Block 17 Building 6A Lot 54,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library (1941).

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Oct. 31, 1771, p. 2, link.

- “Cash Accounts, April 1767,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-07-02-0337; “Cash Accounts, May 1769,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-08-02-0139; “[May 1770],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-02-02-0005-0012; “Cash Accounts, May 1771,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-08-02-0313; “[March 1772],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-03-02-0002-0006.

- “The Flat Hat Club,” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 25 (Jan. 1917): 162; Jane Carson, James Innes and his brothers of the F.H.C. (Williamsburg: 1965); “Thomas Jefferson to Thomas McAuley, 14 June 1819,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-14-02-0392.

- “Original Records of the Phi Beta Kappa Society,” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 4 (April 1896): 220, 223, 240.

- [George Tucker], The Valley of Shenandoah: Or, Memoirs of the Graysons (New York: C. Wiley, 1825), 2:223, link.

- Robert D. Ward, An Account of General La Fayette's Visit to Virginia, in the Years 1824–25 (Richmond: West, Johnston & Co, 1881), 43, link.

- Benson J. Lossing, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1860), 2:278, link.

- Some locals accused the tavern’s last proprietor, Robert Blassingame, of burning the tavern to collect insurance money. [A Warwicker], “Reminiscences,” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 15 (July 1906): 51–54.