Finding The Child’s First Book

If you’ve spent much time around small children, you know that they can be rough on their books. Torn pages, rumpled covers, and lost copies are familiar problems for parents. For that reason, among others, most of the books that schoolchildren used in centuries past have not survived into the present.

At the Williamsburg Bray School, where hundreds of free and enslaved Black children received an Anglican education between 1760 and 1774, students learned from several books depending on their reading ability. The first book that these students encountered as they learned to read was The Child’s First Book. Small, inexpensive, and often tattered by small hands, almost all copies of the book were discarded over the years. Until very recently, historians were unable to locate a copy.

After the Bray School building was rediscovered in late 2020, Colonial Williamsburg worked to learn more about the school and the children taught there. Knowing the importance of The Child’s First Book to the literacy education of the Bray School students, Colonial Williamsburg’s Curator of Maps and Prints Katie McKinney spearheaded a search. Through perseverance and a little bit of luck, a copy was located in late 2023 in an archive in Halle, Germany. The rediscovery of The Child’s First Book will help Colonial Williamsburg more vividly tell the fascinating story of Black education in the eighteenth century.

What Did Students Learn at The Bray School?

Sewing, reading, and religion were core to the Williamsburg Bray School’s curriculum.

Stitched Together

London printers John and William Oliver produced thousands of copies of The Child’s First Book for the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), an Anglican missionary organization founded by Thomas Bray. The SPCK subsidized the book’s sale to its members. This allowed the Associates of Dr. Bray, a philanthropic group also founded by Thomas Bray which established the Bray Schools, to purchase the books cheaply and distribute more than a thousand copies to North American schools and ministers.1

The Associates of Dr. Bray sent more copies of The Child’s First Book to Williamsburg than any other book. They sent fifty copies in 1760, when the school began, forty the next year, and fifty more in 1763.2 Representing the first step of a student’s reading journey, the book would have been familiar to every Bray School student. Not every student stayed in the school long enough to read more advanced texts, like the Bible or the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. The school’s administrators complained in 1762 that some enslavers withdrew students “before they received any real Benefit” of religious instruction, once they had become old enough to perform useful labor.3 For these students, The Child’s First Book may have been one of the only books they encountered at the school.

Rediscovery

For years, historians could only guess at the contents of The Child’s First Book.4 It was as important as it was elusive. “The title of the book was pretty generic,” said McKinney. Was it a primer? Was it even a book? Other candidates included a single sheet with an alphabet called “Child’s First Book,” which was designed to be pasted to a board. McKinney notes, “We needed to find some other identifying information.”

Eventually McKinney found a new clue. The minutes of an SPCK committee meeting referred to ordering 5,000 copies of The Child’s First Book from printer John Oliver.5 Searching for John Oliver’s name allowed McKinney, working with Laura Wasowicz at the American Antiquarian Society, to discover that one copy remained in the Library of the Francke Foundation (Bibliothek der Franckeschen Stiftungen) in Halle, Germany. The creator of the Francke Foundation was August Hermann Francke, a German Lutheran philanthropist whose work, like his contemporary Thomas Bray, focused on religious education. The librarians of the Francke Foundation graciously scanned the book for Colonial Williamsburg.

Reading Lessons

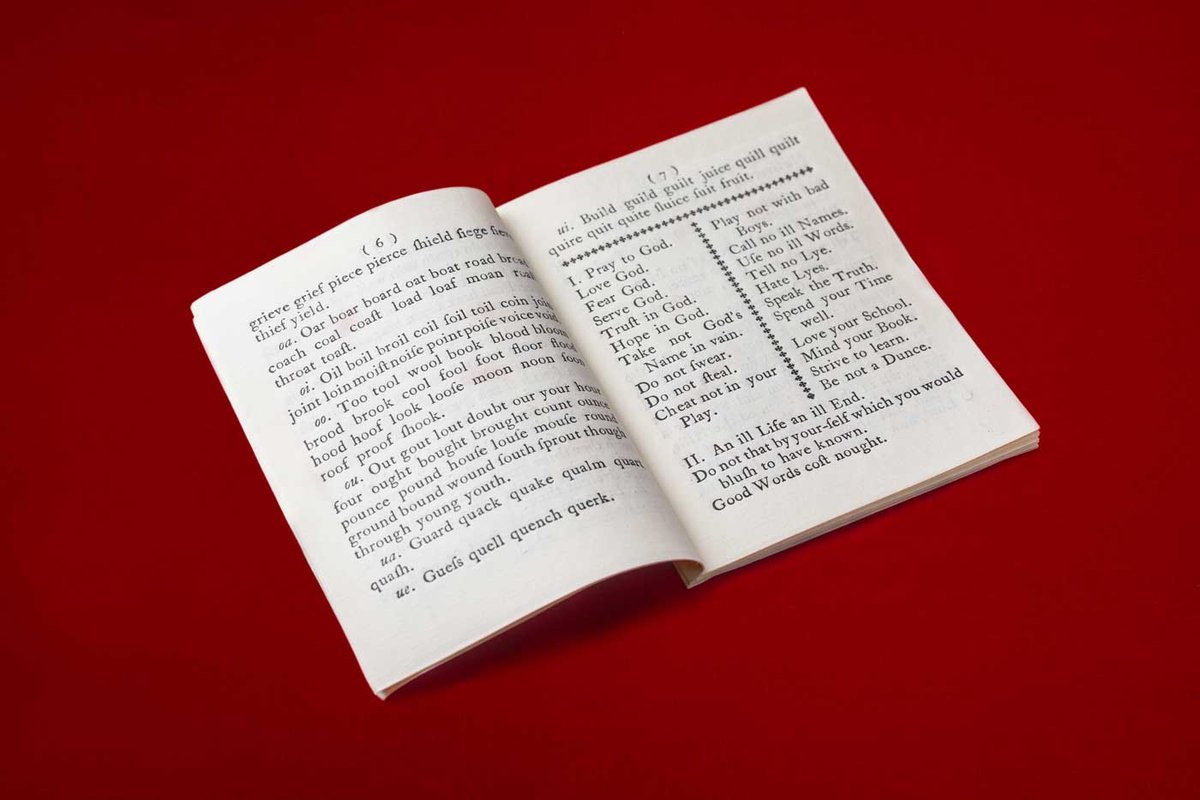

Once Colonial Williamsburg received the scanned version of The Child’s First Book, a few things were apparent. As expected, it was a small, inexpensive primer used for early reading instruction. Slightly smaller in dimensions than a standard postcard, it was only 32 pages. Being so small, it was not bound but sewn together at its edge.

The Child’s First Book contains no preface or instructions. The first page of the book introduces the alphabet in lower and uppercase printed letters. It begins with a series of exercises that would introduce readers to the alphabet. Early readers would have used the book for oral literacy lessons, where the teacher asked students to spell letters aloud, and then pronounce them. They would start with short meaningless syllables and build up to bigger units like words and sentences. Bray School students would have spent much of their day working through these exercises. The book culminates with reading lessons based on short religious passages and prayers.6

Blocks of type being prepared for the reproduction of Child’s First Book at the print shop.

Interpretation

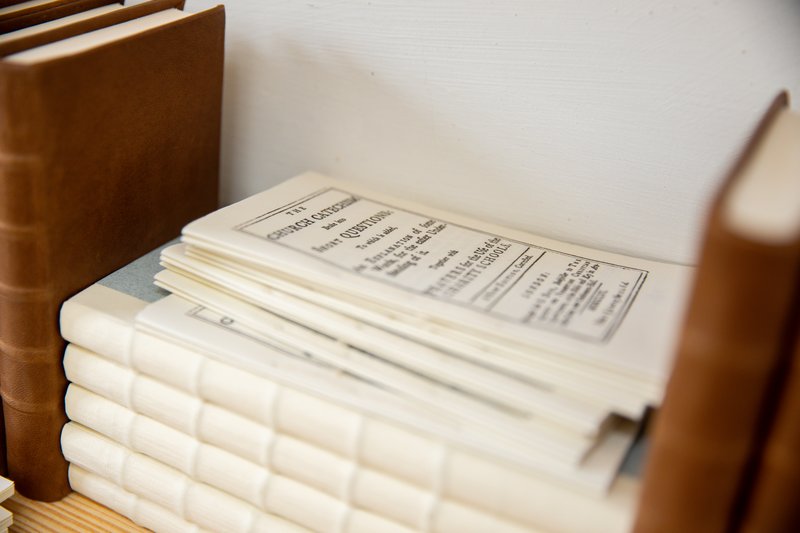

After the rediscovery of The Child’s First Book, Colonial Williamsburg’s Printer began producing replicas for interpretation at the Bray School site. They typeset two sixteen-page forms (Journeyman Supervisor Peter Stinely found the many hyphenations “verrrry annoying”), folded them, and stitched them. They will help visitors better understand what it was like to be a student at Bray School.

While the other books on the Bray curriculum were important, this one was particularly meaningful, according to McKinney, since for the students, “it was key to unlocking the skill of reading.” Its small size is also a reminder, according to McKinney, of “how young the children who attended the school were.”

Colonial Williamsburg has been doing research on early Williamsburg for a century. It’s not every day that we reconnect with a missing part of the past. The Child’s First Book gives us one exciting piece of a much larger puzzle in the story of Black life in revolutionary Williamsburg.

Sources

- The subsidy is noted in “An Account of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge” in Frederick Cornwallis, A Sermon Preached in the Parish-Church of Christ-Church, London, on Thursday April the 29th, 1762 (London: J. and W. Oliver, 1762), 75. “Catalog of Books for Home and Foreign Libraries, 1753-1817,” Manuscripts of the Associates of Dr. Bray, Bodleian Library (Oxford, Eng.), accessed through British Online Archives.

- John C. Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery: The American Correspondence of the Associates of Dr. Bray, 1717-1777 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985), 144–46.

- Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery, 186.

- E. Jennifer Monaghan, Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America: Literacy Instruction and Acquisition in a Cultural Context (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005), 259.

- “Catalog of Books for Home and Foreign Libraries, 1753-1817.”

- Ross W. Beales and Monaghan, “Literacy and Schoolbooks,” in The Colonial Book in the Atlantic World, A History of the Book in America, Vol. 1, eds. Hugh Amory and David D. Hall (Cambridge University Press, 2000), 383.