What Did Students Learn at the Williamsburg Bray School?

At its original location, the Williamsburg Bray School stood near the campus of the College of William & Mary. Between 1760 and 1774, the school’s students walked to school every day except Sunday. They arrived at six o’clock in the morning in the warmer months and seven o’clock in winter.1 As they shuffled in, they might have seen and overheard William & Mary students discussing their studies in topics like ancient languages, mathematics, and moral philosophy.2

Bray School students received a much narrower formal education. Ann Wager, the school’s only teacher, taught reading, religion, and (to the girls) needlework.3 The school instructed students in the “Principles of the Christian Religion according to the Doctrine of the Church of England.” As part of this religious education, students would encounter the “Parts of the Holy Scriptures” that taught them “to be faithful & obedient to their Masters” and “diligent in their Business.” The Bray School sought to mold Black children into obedient, productive workers.4

But many of the students who attended the Bray School had other ideas. They took the skills and knowledge they learned at the school and applied them to their lives in ways that the school’s supporters did not intend. While the Bray School’s curriculum attempted to strengthen slavery and racial hierarchy, some students taught white enslavers their own lessons.

Anglican Instruction

Established by an Anglican missionary organization called the Associates of Dr. Bray, the Williamsburg Bray School attempted to introduce Black children to the Anglican Church. The Anglican Church (or Church of England) was the officially established religion in colonial Virginia. William Yates and Robert Carter Nicholas, two of the school’s early administrators, directed Wager to teach the students to pray at night and before meals, as well as how to “behave in a proper Manner” in church, “kneeling or standing” as directed.5

Anglicans believed that reading certain texts, especially their church’s Book of Common Prayer, was essential to their religious practice.6 For that reason, Anglican missionary organizations like the Associates of Dr. Bray regarded literacy instruction as the first step toward religious conversion. They purchased and sent hundreds of books to the Williamsburg Bray School between 1760 and 1771.7

What Books Did Bray Students Learn From?

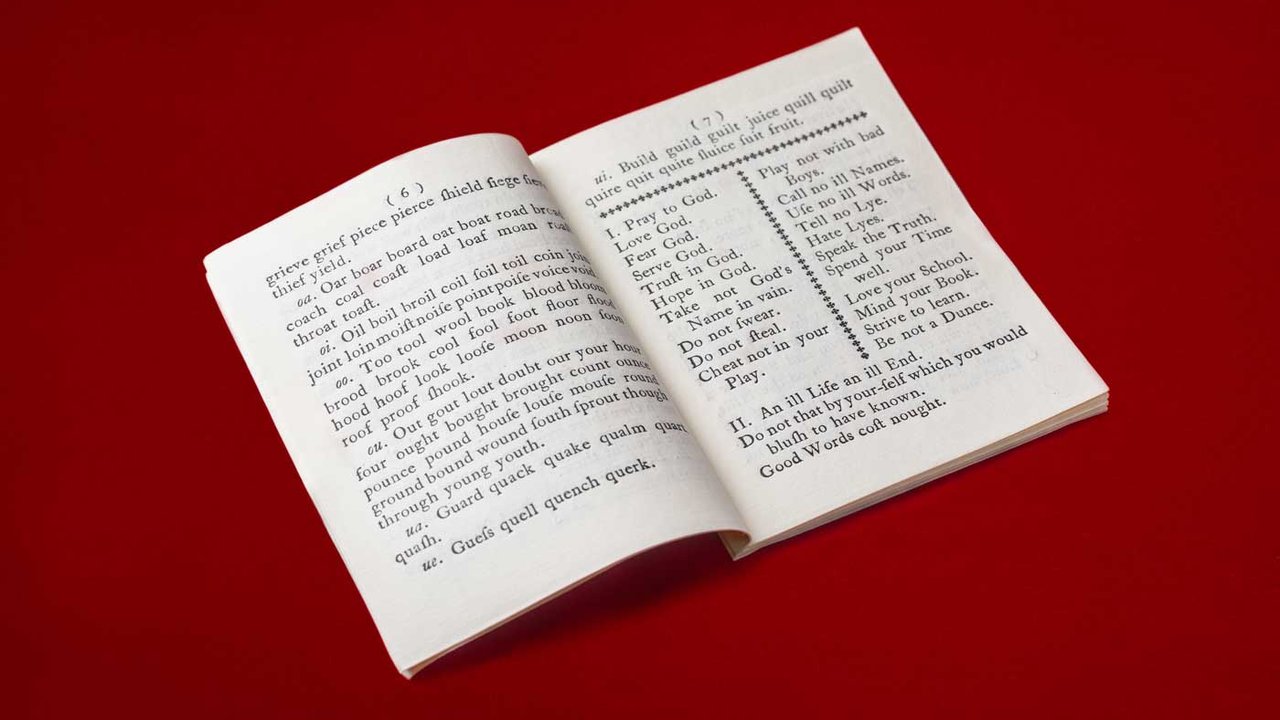

The first book that students encountered was called, appropriately, Child’s First Book. It was a “primer,” meaning that its purpose was to help children learn to recognize and say aloud the name of a letter when they saw its shape. The book began with syllables, then introduced longer words, allowing students to eventually work their way up to four-syllable words. After students completed the primer, next was a “speller,” which taught reading and pronunciation by breaking words from prayers and religious texts into syllables and syllable combinations which students would read out loud. Henry Dixon’s The English Instructor served this purpose for the Williamsburg Bray School.8

Some enslavers ended students’ education when they became old enough to perform useful labor. Robert Carter Nicholas complained in 1765 that several enslavers sent children to the school only “to keep them out of Mischief” or to make them “more handy & useful.” They withdrew students just as they began to read, but “before they had received any real Benefit” of religious instruction. Those students who remained would learn to read more complicated religious texts, such as the Book of Psalms (or “psalter”), the New Testament, the Book of Common Prayer, and the Bible. Ranging in age from 3 to 10 years old, Bray School students had a mix of reading ability and would have been working from different books.9

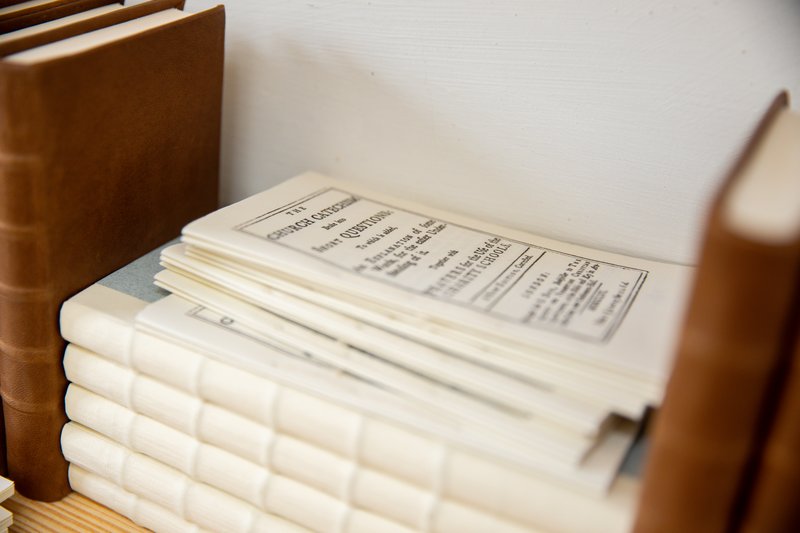

Child’s First Book

Recently located by Colonial Williamsburg, Child’s First Book was the most basic instructional text used at the Bray School. Through continued instruction, students were expected to progress to more advanced religious texts, especially the Anglican Book of Common Prayer and the Bible.

Needlework

At the Bray School, Wager was expected to teach girls needlework. The school’s administrators likely hoped that teaching this useful skill would help convince enslavers to send female students. The Associates of Dr. Bray believed that it was preferable to employ a “Mistress” rather than a “Master” of the school, so that she could “teach the girls to sew[,] knit &c.” The school’s administrators included among its regulations that the teacher “shall teach her female scholars knitting, sewing and such other things as may be useful to their owners.”10 Girls attending the Williamsburg Bray School likely learned needlework by completing marking samplers, which required them to sew letters and figures. This work may have reinforced their efforts to acquire literacy.

Formal and Informal Education

The school’s supporters sometimes expressed the idea that education would make enslaved people more compliant and valuable. Reverend John Waring, secretary of the Associates of Dr. Bray, wrote that enslaved people who were “good Christians” were more likely to “make honest faithful & industrious Slaves than those who have no fear of God.” The school’s regulations instructed Wager to “discourage Idleness & suppress the Beginnings of Vice” among the students. Additionally, the school’s administrators explained, teaching needlework to female students would make them more “useful to their Owners.”11

But not all white Virginians agreed. Yates and Nicholas complained in 1762 that some enslavers refused to send children to the school because they feared that it would be “dangerous” to “enlarge the Understandings of the Negroes,” since it would make them “more impatient of their Slavery” and “more likely to rebel.” These enslavers, they wrote, believed that the “most sensible [perceptive] of our Slaves” were the most “wicked & ungovernable.”12

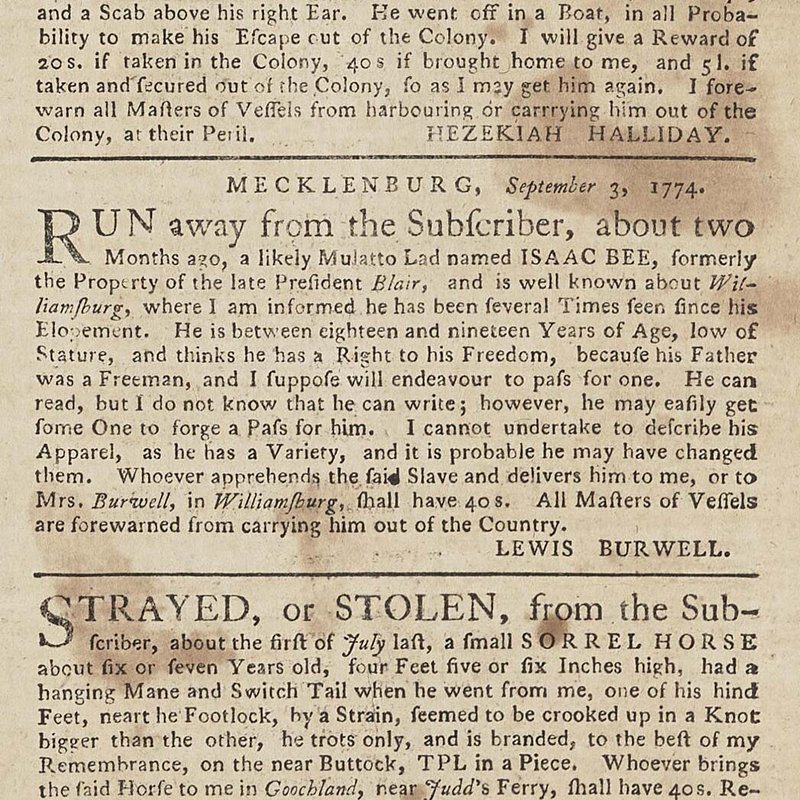

Indeed, some Bray School students did challenge slavery. When a student named Isaac Bee ran away from his enslaver Lewis Burwell, the advertisement seeking him noted that “He can read, but I do not know that he can write; however, he may easily get some One to forge a Pass for him.” It is possible that Bee or other students built on their reading lessons to teach themselves to write.13 Education could be a powerful skill in helping enslaved people navigate toward freedom.

In addition to learning to read Anglican texts, students also continued to learn from their communities and families. Yates and Nicholas wrote, “I fear that most of the good Principles” taught to students were erased “when they get Home, by the bad Examples set them there.”14 The lessons that students took from the Bray School were often at odds with the informal education that they encountered outside the classroom. The Bray School taught students to obey, but their own communities did not necessarily reinforce this.

While the Bray School students received an education, it wasn’t always the education that the school’s supporters intended. The Associates of Dr. Bray funded the school with the aim of introducing students to Anglican Christianity. But the school also equipped students with knowledge and tools that could be used to challenge their enslavement.

Sources

- John C. Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery: The American Correspondence of the Associates of Dr. Bray, 1717-1777 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985), 190.

- According to Colonial Williamsburg’s Shirley and Richard Roberts Architectural Historian Jennifer Wilkoski, “Where the building first stood, the campus of William & Mary is visible from one side of the house, and out the front windows is the Wray carpentry site. We have two original window sashes that they could have been looking out of, seeing these two very different worlds: the world of William & Mary on one side, and the industrial world of the carpentry yard on the other side.” On subjects taught at William & Mary, see Mary Goodwin, “The College of William and Mary,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library (1967), 33, 44–45, 49.

- “[Enclosure: Regulations], 30 September 1762,” in Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery, 189–92.

- Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery, 191.

- Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery, 191.

- E. Jennifer Monaghan, Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America: Literacy Instruction and Acquisition in a Cultural Context (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005), 16, 143.

- For records of two book shipments, see Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery, 146, 158.

- Monaghan, Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America, 13; Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery, 146, 158.

- Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery, 146, 158, 186; Monaghan, Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America, 13.

- Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery, 144–46.

- Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery, 267, 191.

- Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery, 186.

- In the eighteenth century, according to scholar E. Jennifer Monaghan, reading and writing were taught separately, with writing usually not being taught to enslaved people. E. Jennifer Monaghan, “Reading for the Enslaved, Writing for the Free: Reflections on Liberty and Literacy,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 108 (1998): 309-41. However, as historian Antonio Bly has shown, most literate self-emancipated enslaved people in Virginia were described in “runaway” advertisements as being able to both read and write. While writing was most likely not taught at the Williamsburg Bray School, some enslaved people may have drawn on their reading ability to learn to write. Antonio T. Bly, “‘Pretends he can read’: Runaways and Literacy in Colonial America, 1730—1776,” Early American Studies 6, no. 2 (Fall 2008): 276–77, 282–83.

- Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery, 241. See also Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery, 186.