An in-Depth Look at Re-Creating an Embroidered Waistcoat for Thomas Jefferson

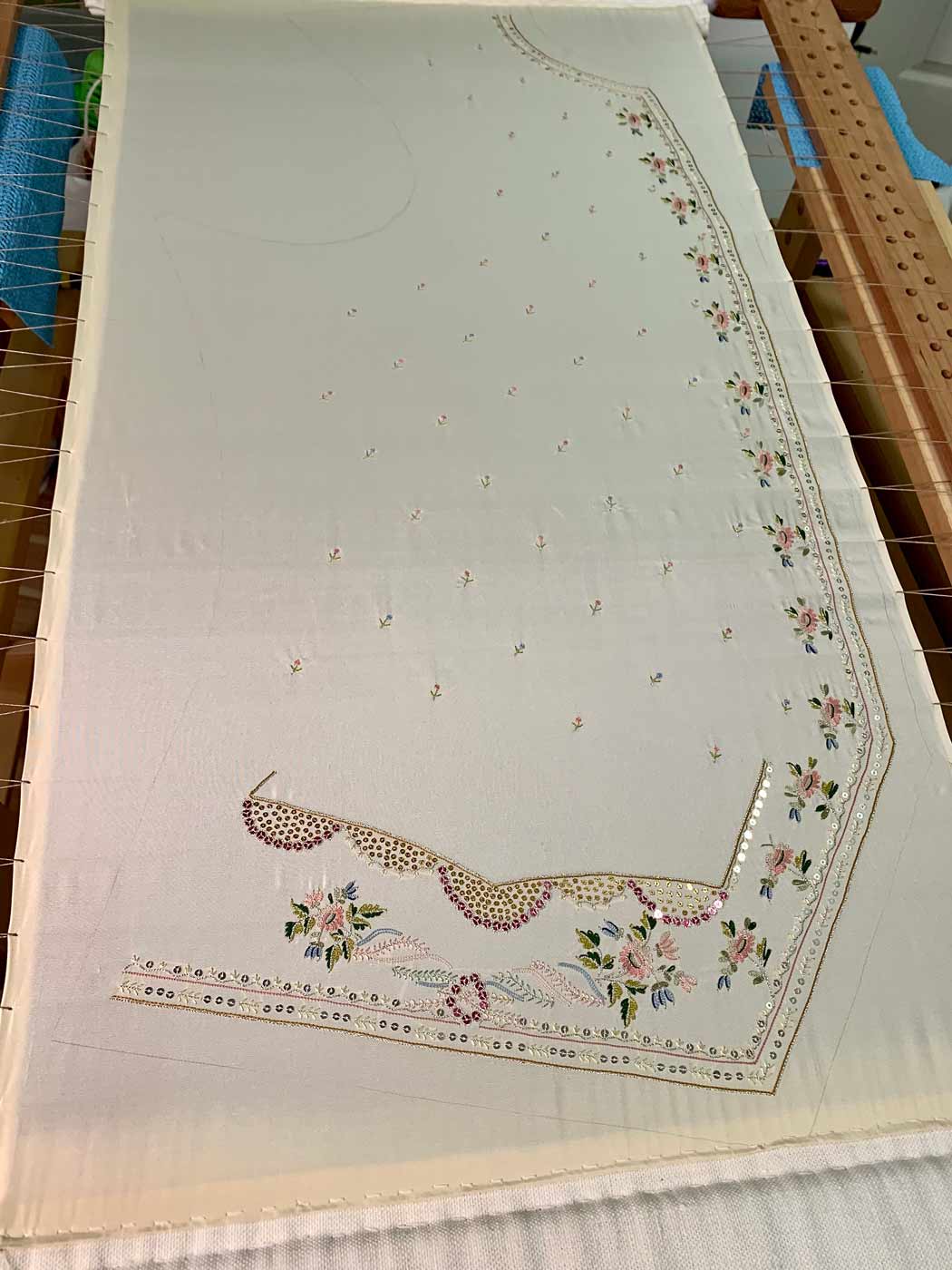

When the Costume Design Center needed to make a new suit for Kurt Smith, who portrays Thomas Jefferson, it included an embroidered waistcoat inspired by one in the collection of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello. It is believed to be one of several embroidered waistcoats that Jefferson acquired while serving as Minister to France (1785–1789).

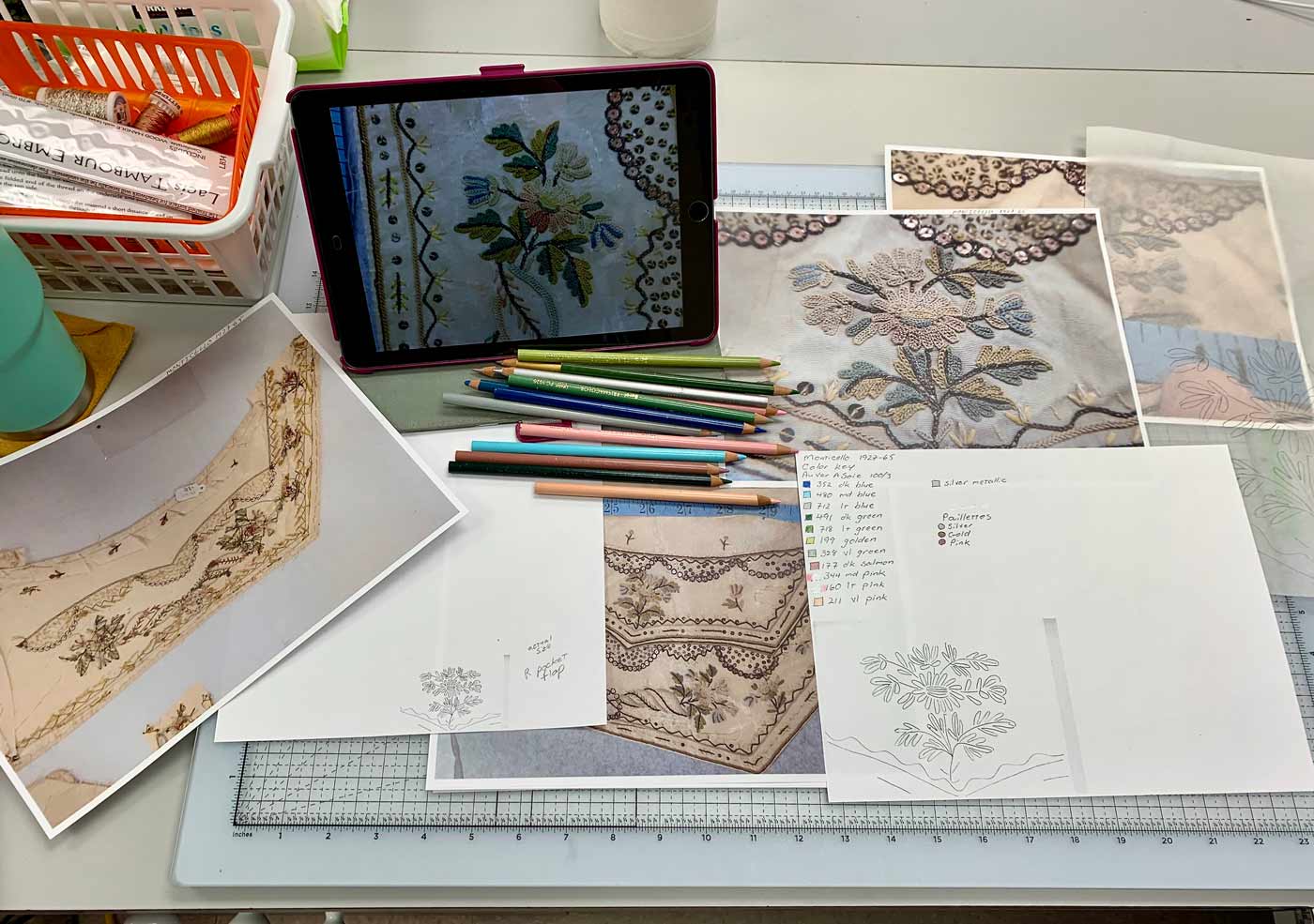

Brenda Rosseau, the Costume Design Center manager, Kurt Smith, who portrays Thomas Jefferson for Colonial Williamsburg, and I visited Monticello to view the original waistcoat and determine how best to proceed with the project. Unfortunately, none of the waistcoats in Monticello’s possession are complete as they were possibly cut up for souvenirs sometime after Jefferson’s death. Fortunately, enough fragments of various waistcoats have been preserved by Monticello which we were able to study to select a design for our reproduction waistcoat. Of the surviving fragments from four different waistcoats, we chose the one with the most and largest remaining pieces.

Numerous pictures and measurements were taken and, using thread swatches, colors chosen for the embroidery threads. One huge advantage of having this garment in pieces is the fact that the back of the work can be seen and studied. This helped determine how it was embroidered and, because the colors are not faded on the back of the work, made color matching much more successful.

Using printed photos of the original waistcoat, the embroidery motifs were traced and scaled to size on the photo copier.

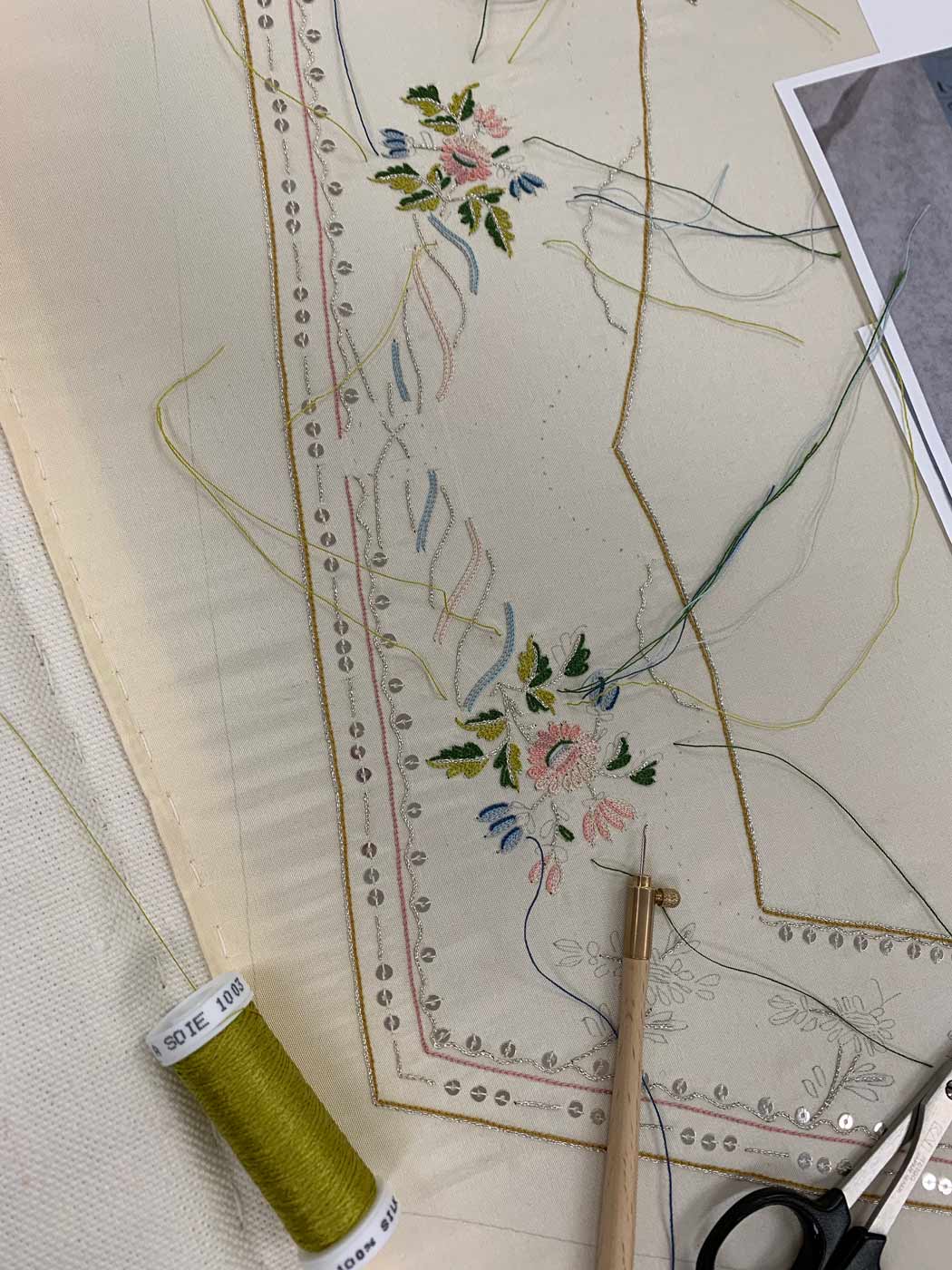

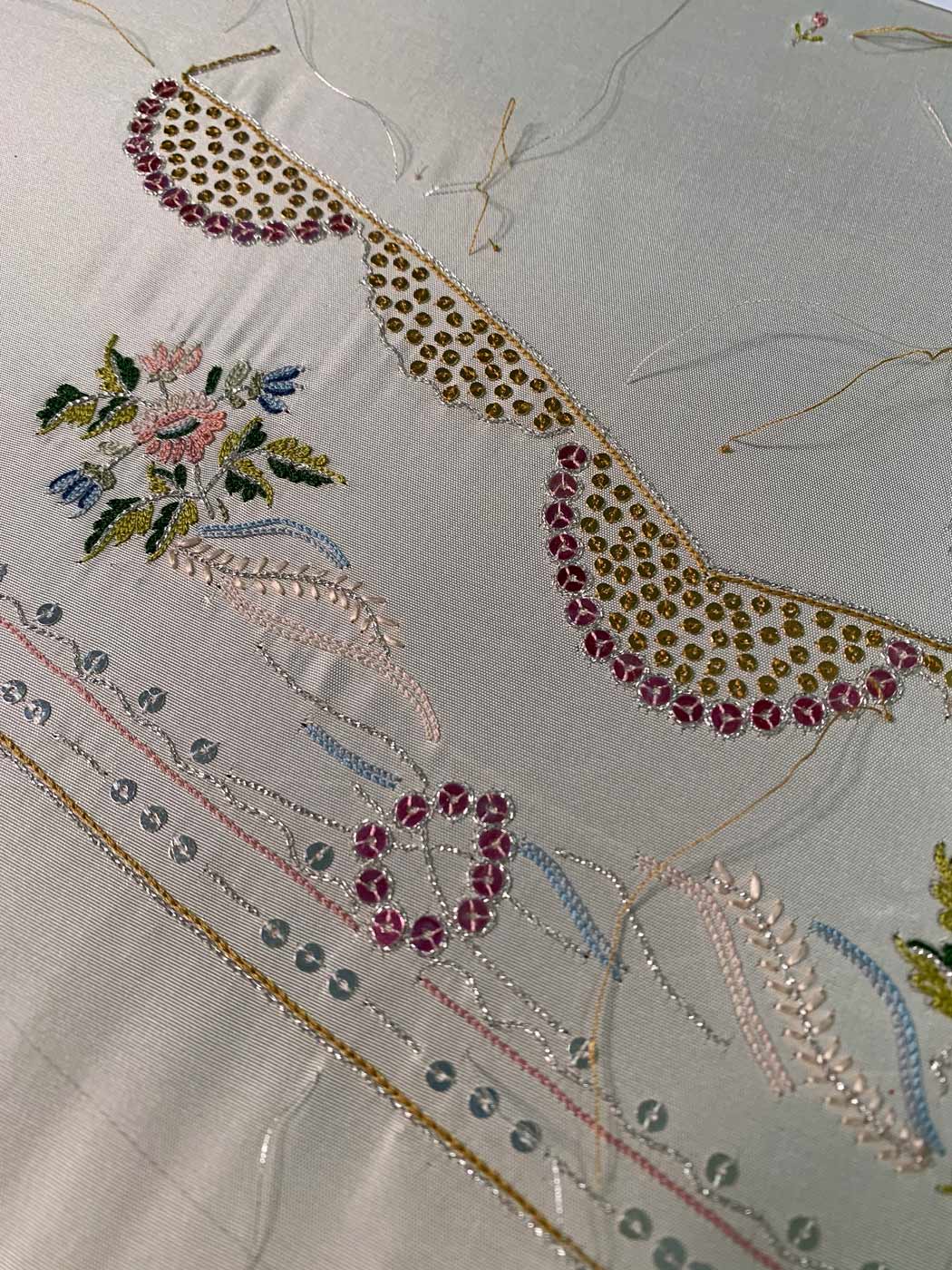

Once the design elements were traced, I embroidered a sample to get a feel for how the design would work in the chosen thread types. The embroidery is primarily tambour work. Tambour embroidery was extremely popular in the 18th century. It looks identical to chain stitch, but is done with a tiny, sharp crochet-type hook. This hook makes the work go much faster than needle stitching, which may have contributed to its popularity in the period.

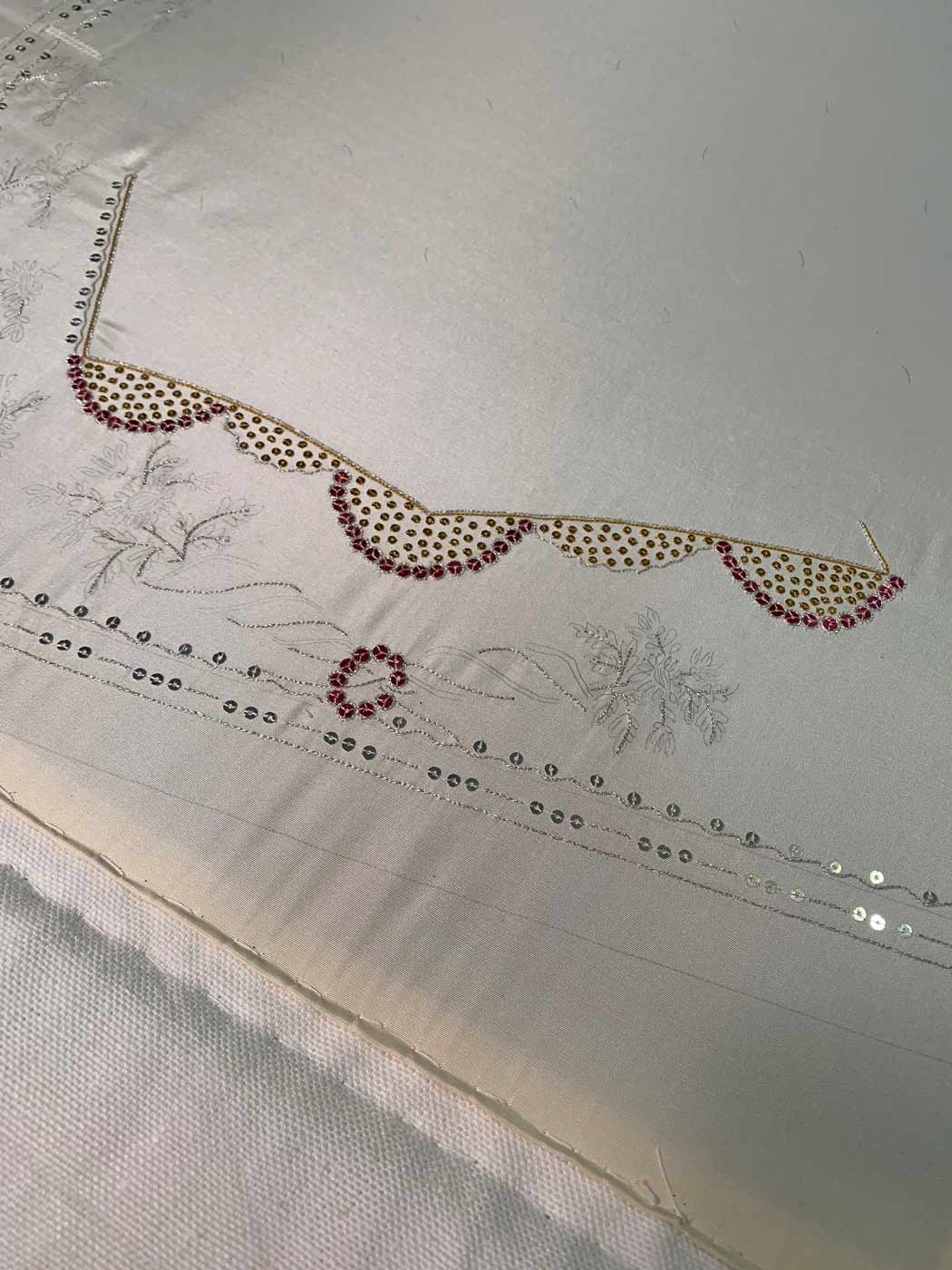

After the elements of the embroidery design were scaled to fit the reproduction waistcoat, they were drawn onto a tracing paper version of the embroidery pattern. By using tracing paper, the design pattern could be traced onto the silk fabric for one side of the waistcoat and then flipped to use on the other side, thus eliminating the need to create two separate emboridery patterns.

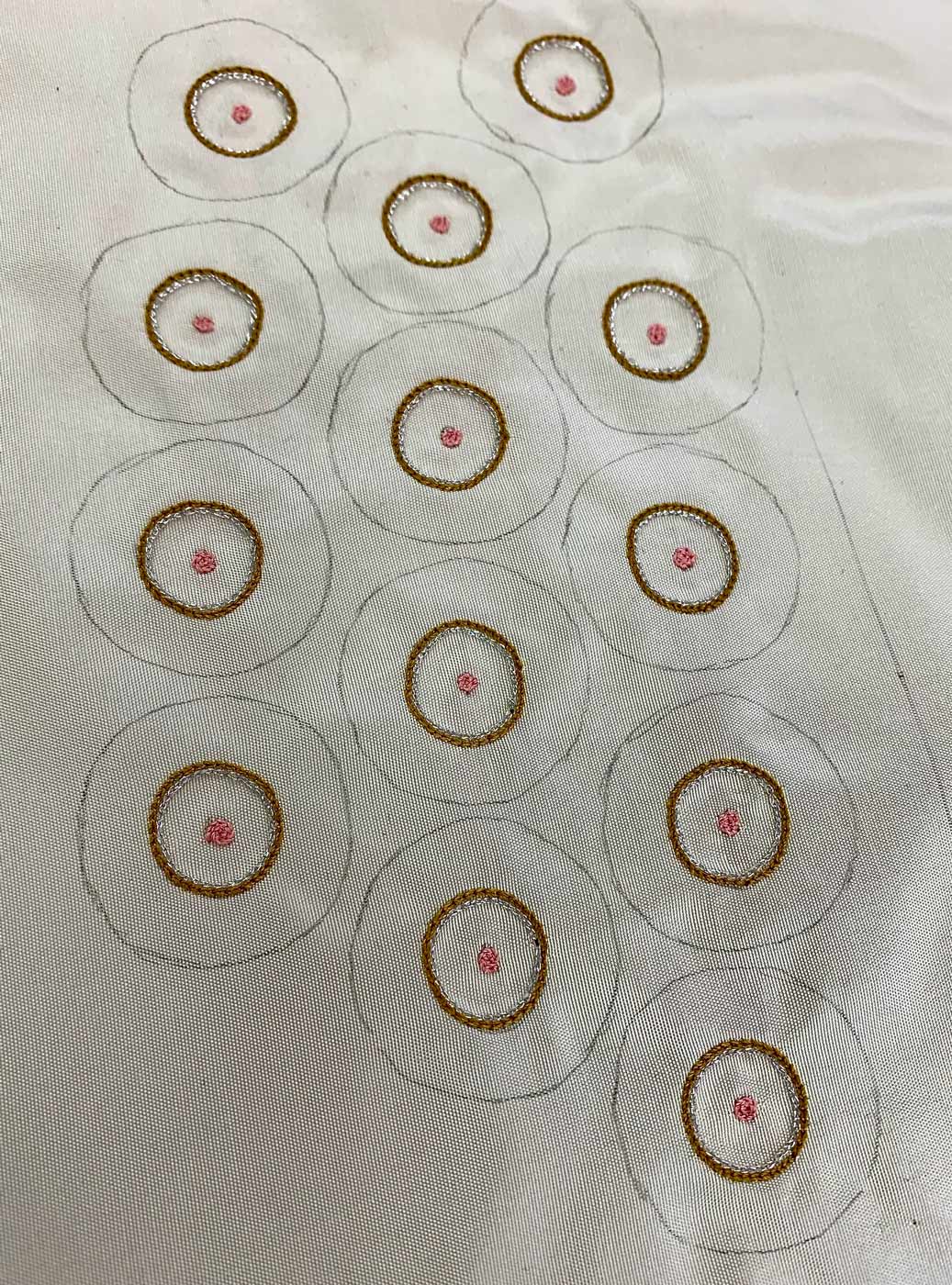

One of the challenges of creating this waistcoat was sourcing the paillettes, or spangles. There are only a few suppliers remaining, and the variety is limited. Paillettes are made by coiling a piece of gold or silver wire, clipping the wire coil into rings, and then pounding the rings flat to make the donut-shaped paillettes. The small seam in the rings reveals that the original paillettes on the waistcoat were made this way, rather than being punched from a sheet of metal.

Our selected waistcoat has three paillette sizes and colors. The gold and silver paillettes are readily available, but not the pink. We know that there were various ways to achieve the colored metals in the 18th century, but most are not cost effective or take longer than we had to create them. After testing a couple of options for coloring silver paillettes, we chose to paint them with a mixture of pink alcohol ink and clear nail polish. This gives a good effect and is fairly resistant to modern dry cleaning practices.

Using a light table, the embroidery design is traced onto the silk fabric with a pencil. The front panels are then stretched onto an embroidery frame. With tambour embroidery, the fabric must be kept very tight or it is impossible to work.

Next comes many, many hours of embroidery! Because I am not nearly as adept at tambour work as my 18th-century counterparts, it took about 225 hours.

During the embroidery process the thread ends are left on the front of the work. This prevents them from becoming entangled on the back during embroidery. Due to the size of the frame, it is much easier to flip it over as few times as possible. The ends were pulled to the back and woven in once the embroidery was complete.

This reproduction was the continuation of an earlier (1990s) Colonial Williamsburg project which brought most of Thomas Jefferson’s surviving wardrobe back to Virginia from collections nationwide. Surviving identified items (generally intact) were surveyed, recorded, meticulously reproduced, and finally returned to their various repositories. The study and reconstruction of this fragmented waistcoat provides a window into Jefferson’s wardrobe and world, as well as into the techniques and skill of the maker.

This project was made possible thanks to a generous donation to help costume our Nation Builder interpreters.

Melissa Mead is the former Accessories Team Leader at the Costume Design Center, having recently retired from Colonial Williamsburg after 17 years of service. Melissa has sewn and crafted for as long as she can remember and one of her favorite pastimes is tatting lace. We wish Melissa well in her retirement!

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.