The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg are home to a breathtaking range of folk and decorative art. Uncover the history behind beautiful objects in masterfully curated exhibitions in our blog series “Amazing Stories. Beautifully Told.”

Today we’re taking a closer look at a painting going on view October 22 in the Blagojevich Gallery. It’s part of the exhibition, “I made this….”: The Work of Black American Artists and Artisans, that was made possible through the generosity of The Americana Foundation.

What is it?

This Portrait of Susanna Cardwell McCausland (Mrs. James McCausland) and Child is one of three paintings attributed to artist Joshua Johnson in Colonial Williamsburg’s collections. Johnson is considered one of the earliest professional free Black painters in America. In this endearing portrait of a mother and child painted around 1805, Johnson used subdued colors to portray the pair together on a period sofa complete with brass tacks.

What’s the story?

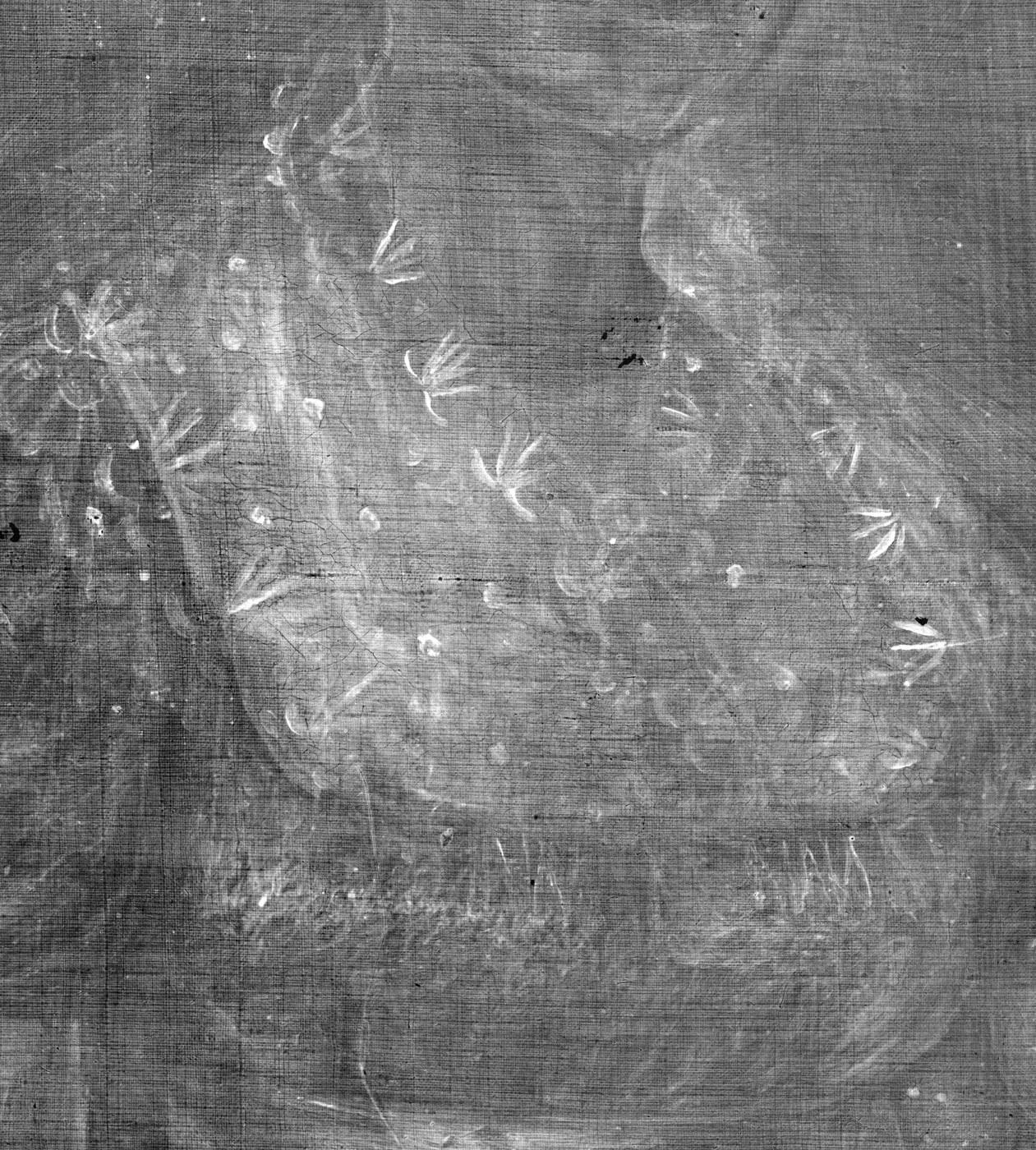

Preparing the artist’s works for exhibition provided an opportunity to examine Johnson’s paintings in the conservation lab and reveal the little-known materials and painting techniques of this artist. Our most exciting discovery was Johnson’s use of drawing with a pencil-like tool to place elements of the composition on the canvas. In this detail of the child’s face (Figure 1), you can see evidence of the artist’s skilled drawing ability. Using a most unusual approach, he drew elements of the composition both below and on top of the paint layers, revealed with infrared photography. In another detail (Figure 2), you can see that the artist, using paint, shifted the baby’s nose slightly lower than in the initial sketch.

Further close examination of the painting also showed a slight variation in the pink skin tones of Susanna. X-ray imaging of the complex paint application on the side of her face where it meets the cap and above her dark dress line revealed that the artist made notable changes in these areas. While Johnson slightly shifted the cap edge (Figure 3) away from her eye, changes to the areas above her dress neckline were more major. The x-rays showed that an initial simple, white material extending from the dress edge was altered by the artist into the more elaborate, transparent kerchief that we see today (Figure 4). These changes would have required the artist to add pink paint in these areas followed by the detailed paint of the changes. The second application of pink in changed areas appears to be more vibrant than the slightly more subdued areas without artist’s changes. However, further examination revealed consistent pigment mixtures in the earliest painted areas as well as those he later changed. While slight fading of red pigments may cause the variation in skin tones, it is also possible a past lining has contributed to this changed appearance.

Why it matters?

With so little known about this important artist, taking a closer look at how he painted provides insight into his working methods. We know he used the basic pigments of lead white, charcoal black, vermillion, and red lakes for this composition, which tells us what was available to him at that time. We have also learned that Johnson sketched the initial composition on a gray ground, then developed the sitters’ features and clothing with paint, continuously refining details, including the unusual technique of drawing again on top of the paint surface as the composition evolved. These clues provide us with a glimpse into how he problem-solved to skillfully turn a two-dimensional blank canvas into a three-dimensional space filled with his sitters that can still touch our lives today. In the future, we’ll take a close look at Joshua Johnson’s Portrait of Ellin North Moale (Mrs. John Moale) (1740-1825) and Her Granddaughter, Ellin North Moale (1794-1803), an earlier work by the artist.

See for yourself

For more information on this portrait painting as well as tens of thousands of objects in our collections online, visit: Portrait of Susanna Cardwell McCausland (Mrs. James McCausland) and Child – Results – Search Objects – The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (history.org). We also invite you to see this remarkable object in person at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg and discover more amazing stories, beautifully told.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.