A look at these popular, colorful, and satirical prints

Today the only macaroni we are likely to think about is that cheesy delight: macaroni and cheese. But the name of this delicious comfort food has a surprising association with fashion and cultural history of the 18th century. Recall that famous tune Yankee Doodle Dandy. Ever wonder why he stuck a feather in his hat and called it macaroni? Me too. I thought that the term that entered into popular parlance around the time of the American Revolution, was used describe sartorially adventurous men and women, but the associations go way beyond the world of fashion and satire, touching the areas of politics, social commentary, behavior, sexuality, food, gender, race, travel, and culture. As I started researching and cataloging our wonderful collection of satirical prints depicting “macaronis,” it became clear that I would need some help coming up with a definition for this complicated figure. Luckily, here at Colonial Williamsburg we have a fantastic team of experts on a variety of subjects, including this one. Michael McCarty, Colonial Williamsburg’s Journeyman Tailor, who’s been conducting extensive and important research that separates fact from fiction about the “macaroni,” described the origin of the phenomenon as such:

“About two decades before our war for independence, an exclusive group of well-travelled young Englishman, self-named the “Macaroni Club,” began meeting at the even more exclusive Almack’s club in London. London newspapers of the time mention the club members dining on the newly imported pasta. Their choice of moniker might have been somewhat self-deprecating; “macaroni” sounds like “maccharone,” Italian for blockhead or fool!”

The name stuck and exploded in popularity to describe a laughable, often strange, or comical character. The term and visual associations were perfect for the exploding print satirical trade in London in the late-1760s and 1770s. Those prints are how we are most familiar with exaggerations of the dress, mannerisms, hairstyles, and behaviors of the macaroni, but they have distorted our modern view how eighteenth-century men and women might have actually dressed. The nature of satire is to take something real (usually threatening or unusual) and exaggerate it out of proportion. In that way, these prints leave out just as much as they actually tell us about what macaronis actually wore and how they behaved.

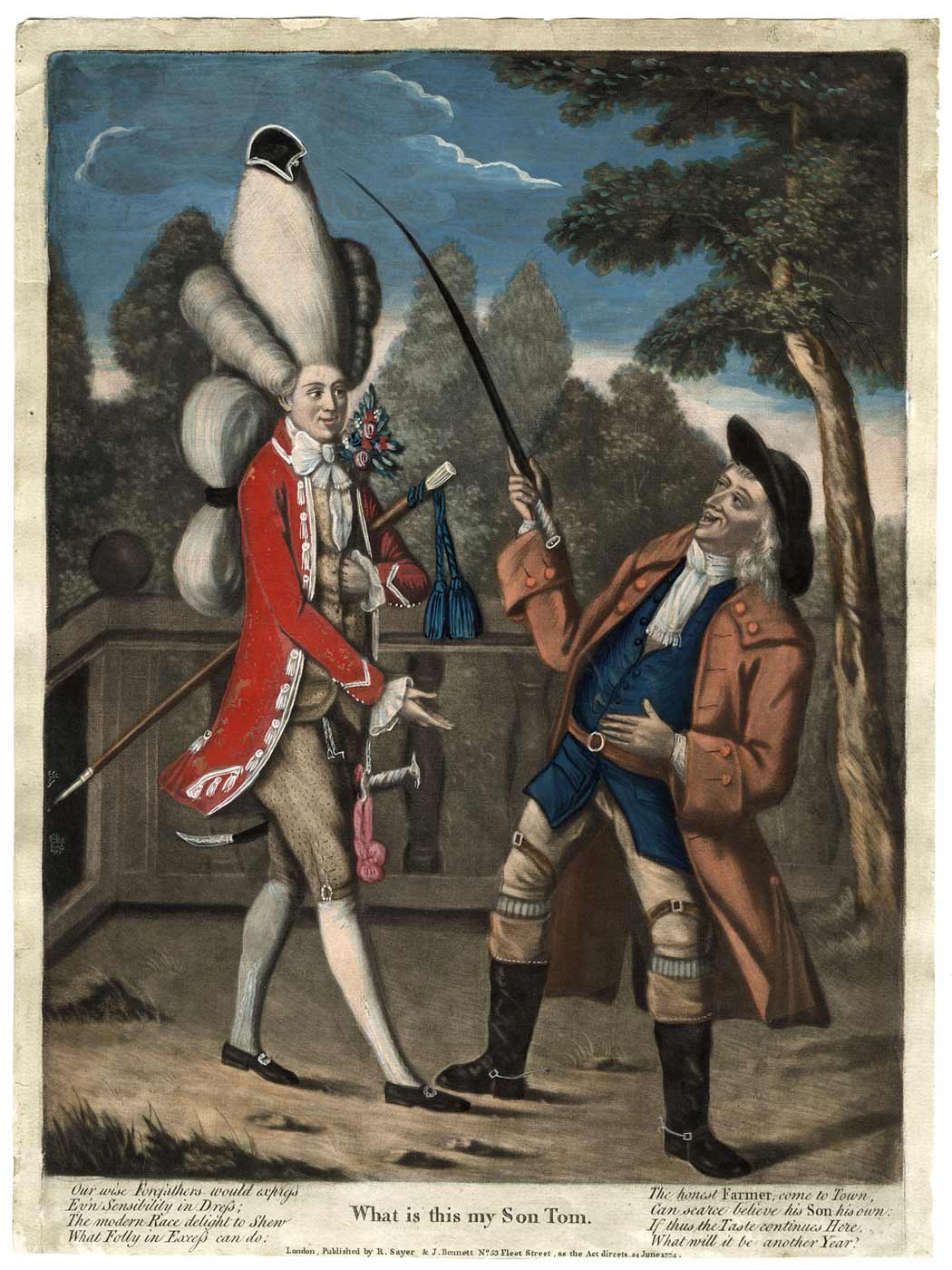

That is why if you’re familiar at all with the macaroni it is likely through the form of a print such as What is this my Son Tom. On its face, the text along the bottom of the print pokes fun (literally) at the generational differences in fashion between this father dressed for the country though he’s visiting the city (which would have looked odd as well) and his decked-out son:

Our wise fathers would expres(s)

Ev’n Sensibility in Dress;

The modern Race delight to Shew

What Folly in Excess can do:

The honest Farmer, come to town,

Can scarce believe his Son his own.

If thus the Taste continues Here.

What will it be another Year?

I asked Michael to help me better understand what is going on in What is this my Son Tom, which depicts the young man dressed in clothing that would have been understood as visual shorthand for “macaroni.” But as Michael pointed out, there were no hard and fast rules for this. In this particular example, he wears (from top to bottom): a tiny hat atop his hair dressed in a towering “toupée” on top and a “club” behind; a large nosegay or corsage; a coat with a shorter skirt; a cane with tassels; an ornate silver-hilted sword with elaborate sword-knot; and silver knee and shoe buckles. According to Michael, 18th-century viewers would have found this entire ensemble ridiculous and nonsensical — and not just the insane toupée. For example, contemporary audiences would have associated the type of coat he is wearing riding, hunting, or sporting which would have looked strange on a city-dweller like this young man. A bit like the trend for wearing high-fashion athleisure everywhere, perhaps? They also would have found his carrying both a cuttoe or hunting sword and cane outrageous as well. Either one on their own used in the wrong context would have looked odd. There are also some, ahem, anatomical associations inferred by the swords that appear in many of these depictions, but we won’t go into that. Though the print doesn’t call him a “macaroni” outright, the printmaker is pointing out the foolish nature of the latest trends in fashion.

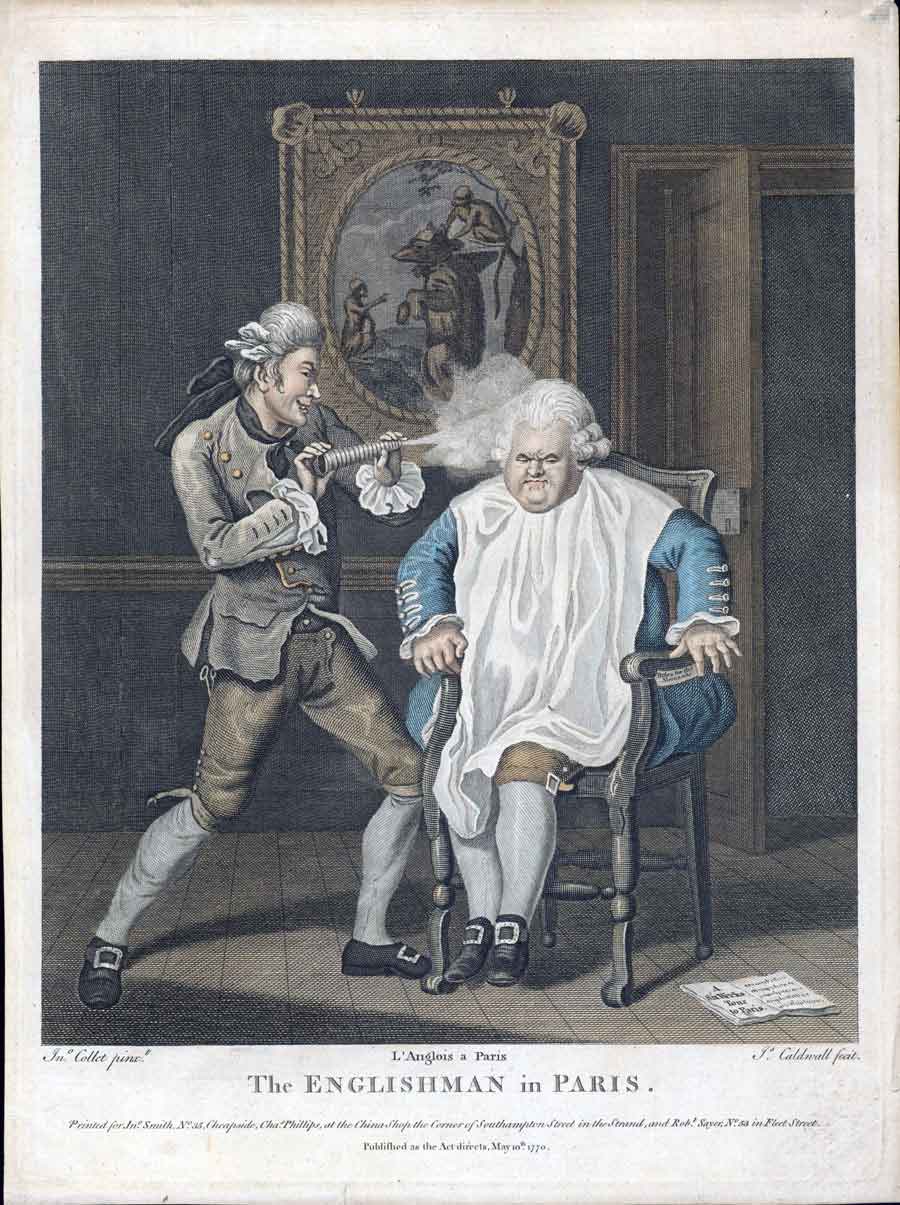

Though the mythology of the macaroni is complicated and obscure, the figure took on a life of its own in the world of prints because they represented something unfamiliar, hard to define, and worst of all, represented foreign influences. English nationalism was on the rise in the late 1760s after their victory in the Seven Years War (called the French and Indian War) resulting in a pride towards all things English and elevated anxiety about the intrusion of Continental, especially French, influences. At the same time, young aristocrats travelled abroad on the Grand Tour, introducing them to foreign customs, dress, hairstyles, cuisine, and manners which was perceived as a threat to English culture and ultimately, the very identity of their country. The macaroni was an urbane character who represented all these things making them ripe for ridicule and they appeared on the scene at exactly the moment that one of England’s greatest artforms was on the rise: the satirical print.

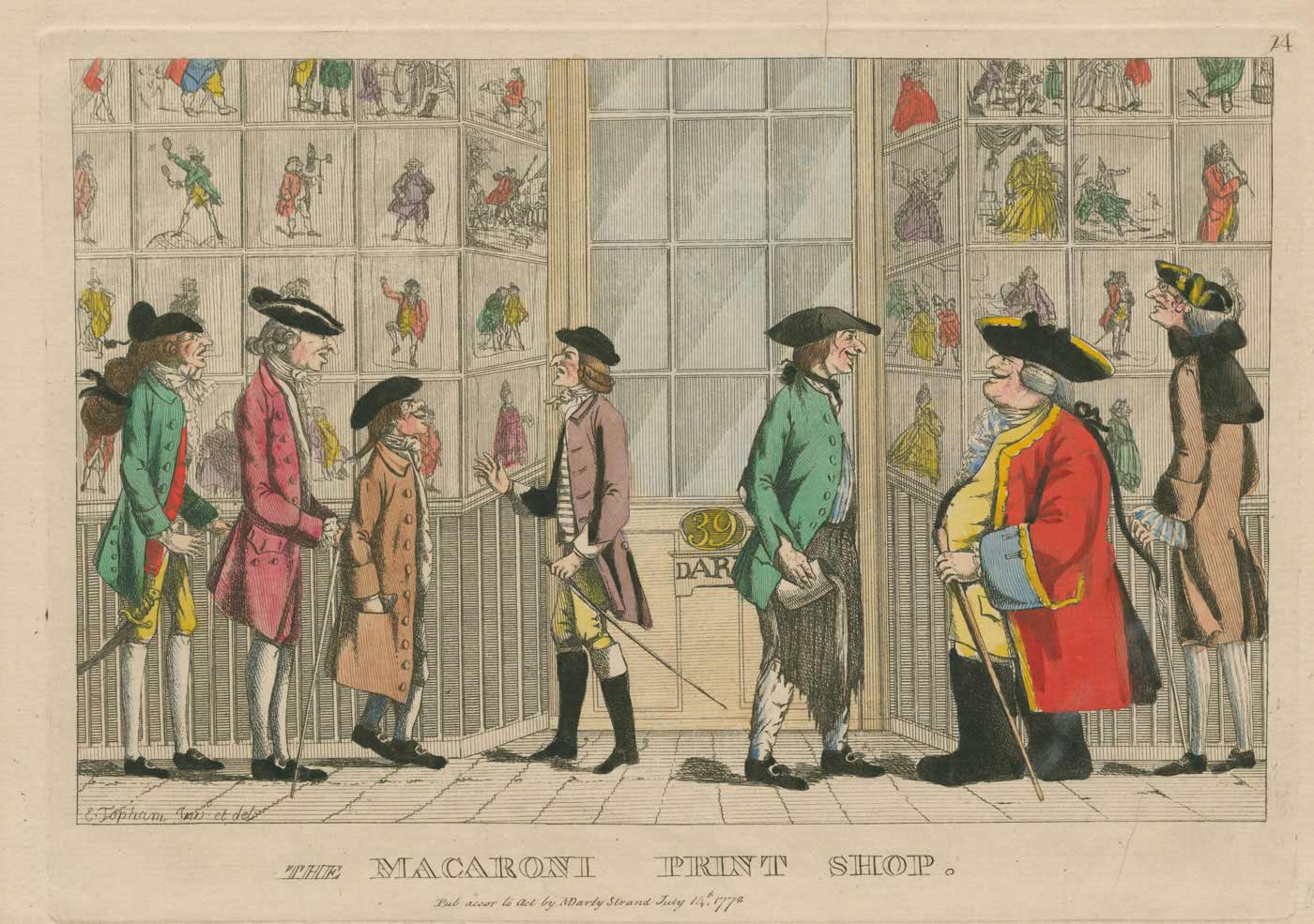

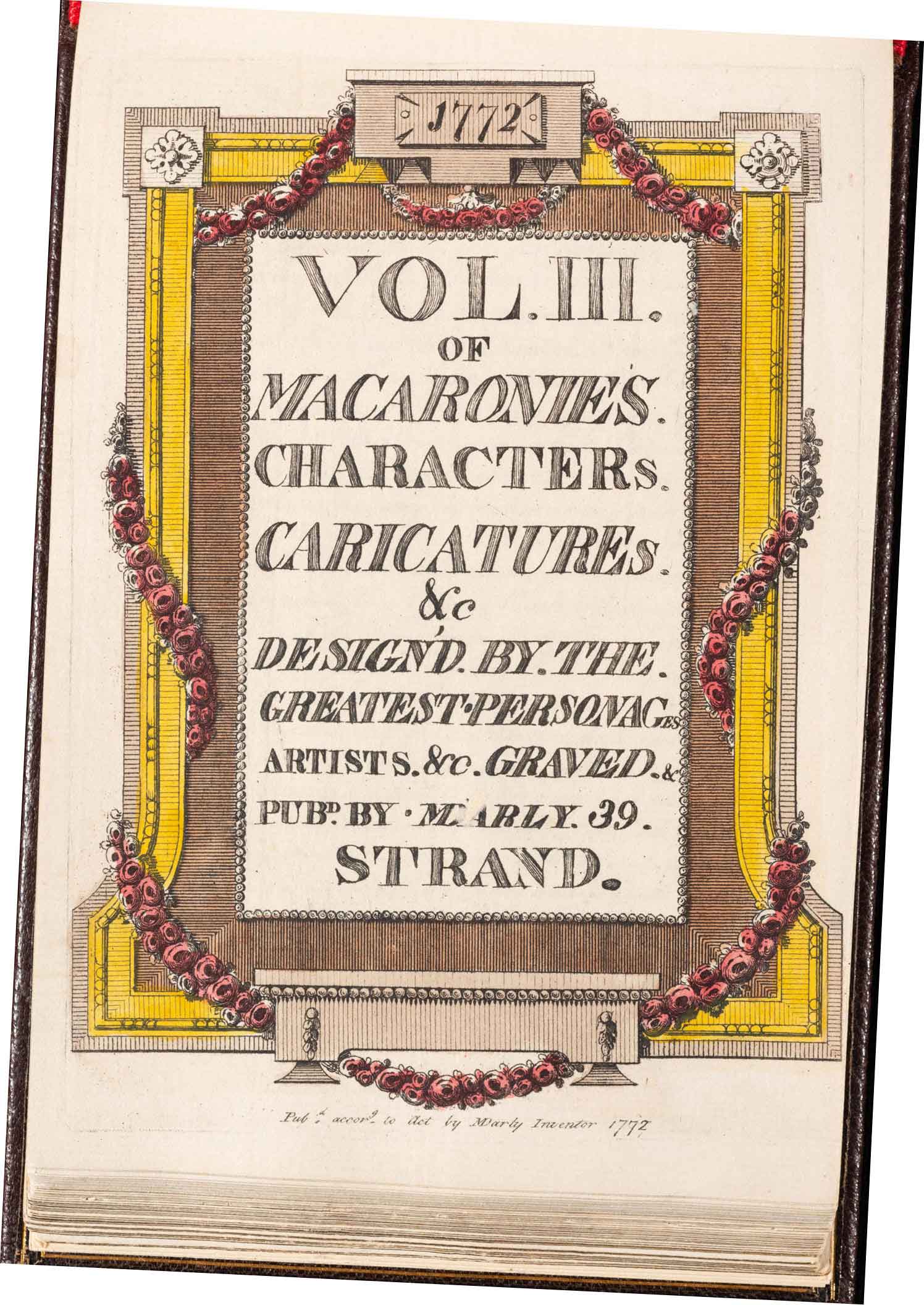

These comedic prints known in the period as “drolls” poked fun at a variety of topics including: politics, famous individuals, fashion, class, taste, gender, race, and current events. The print industry was on the rise in the 1760s and took off in the 1770s, becoming an important commodity and export for England. It was also a powerful tool for social commentary. Two of the most prolific publishers of “drolls” were Matthew (Matthais) and Mary Darly, a husband-and-wife team who capitalized on the popularity of satirical prints, particularly the caricature, which was the practice of making a likeness with exaggerated mannerisms or features to create a comic effect. This form was brought back by aristocratic Britons who visited Italy on the Grand Tour. The Darlys catered to this audience by publishing a prolific assortment of caricature prints during the 1770s. Many of the Darly’s prints characterized the subjects in the stereotypical fashion and manners of the “macaroni” and subsequently, regardless of subject or reality, the Darly’s prints were known as “macaroni prints.”

Their most famous work was their encyclopedic Caricatures which were published in six volumes between 1771 and 1773 (Colonial Williamsburg owns volumes 1-3). According to the British Museum, most prints signed “MDarly” were by Mary Darly, but it also appears to be a cipher for both their work. Most of the caricatures represent actual men and women in London life and they were based on drawings by the Darlys, fellow artists, aristocrats, or amateur artists and those submitted to them by amateur artists lambasting their friends, artists, and characters. Due to strict libel laws, the names of the individuals were obscured, making identifying the caricatures a kind of game. These likenesses would have been recognizable to a small subset of London society who were in on the joke. What’s lost today about many of these prints is that just because someone is fashioned as a “macaroni” does not mean that they dressed or acted like that in reality, rather they became the butt of the joke when they were cast in the trappings of a recognizable humorous character. They were kind of the memes of the 18th century.

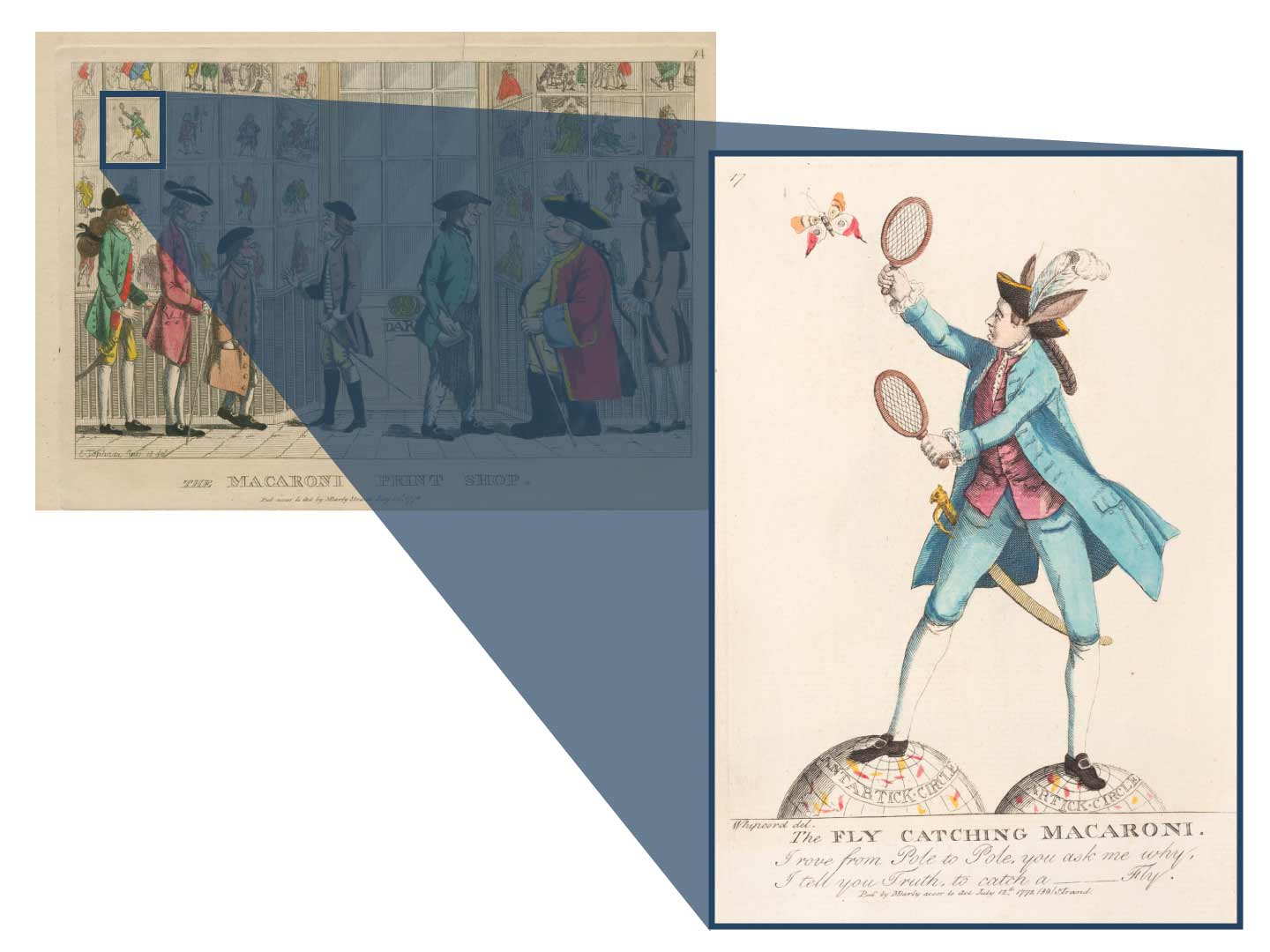

The prints, which appear in the windows of the Darly’s print shop at 39 Strand in London, depicted in the print The Macaroni Print Shop are an example of the Darly’s ingenious marketing skills. The windows are filled with representations of the actual prints that appeared in the Caricatures series and the figures lined up to view them are the very types of comical characters represented in the prints. For example, The Fly-Catching Macaroni caricatures the British naturalist Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820) who served as president for the Royal Society for 41 years and took part in several well-known expeditions, including Captain James Cook’s first great voyage from 1768 to 1771 that traveled to Brazil, Tahiti, and Australia. Back in London, Banks was a driving force for collecting and propagating seeds at the Royal Botanic Gardens. A celebrity du jour in 1772, Banks is depicted here hopping from “pole to pole” while holding two nets with which to catch a butterfly. He wears the requisite sword and is ridiculed by the addition of a large ostrich plume (typically a female fashion, seen in certain military units, but not in civilian men’s hats) and asses ears protruding from his hat. Why was he cast as a macaroni, hopping from pole to pole while catching butterflies? The print pokes fun at Banks’ world travels and the absurdity of traveling the globe in search of small insects. The print, which signed “Whipcord del.” (meaning drawn by Whipcord), which could be a nom-de-plume for the artist who originally drew the caricature of Banks.

Although Banks has been identified by scholars, the identities of other individuals remain lost to time, but would have been identifiable to at least a small group of individuals within London society. The figure in the The Noviciate of a Macaroni is unidentified, but he represents the young men who would have enjoyed entertainments such as dancing, theater, musical performances at pleasure gardens, like Ranelegh Gardens in Chelsea which at the time was just outside of London. The word Noviciate, refers to the period of training that a prospective member of a religious order undergoes before taking vows, suggesting that these pleasure gardens were training grounds for “macaronis.”

While these prints sought to mock the macaroni, they are deceptive and do not reflect the actual dress, attitudes, and features of the actual “macaroni.” The caricatures, which started out as an exclusive joke, appealed to a larger subset of culture because everyone found humor in the macaroni — a figure that, in the case of print culture, represented among other things, pride in dress, foreign influence, novelty, affectation, ignorance of class barriers, and pretension. The prints make it clear that there was not one type of macaroni, but it was a comedic lens through which eighteenth-century Britons could view a multitude of individuals.

For more, just search “Macaroni” in our online collections and enjoy these colorful prints.

The author would like to thank Michael McCarty, Neal Hurst, Mark Hutter, Margaret Pritchard, Sarah Lockwood, Erin Lopater, and Jason Copes.

Katie McKinney, Margaret Beck Pritchard Assistant Curator of Maps and Prints, has worked for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation for four years. She holds a master’s degree from the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture at the University of Delaware and a BA in art history and history from James Madison University. A native of Williamsburg, she fell in love with the Historic Area and history at the age of nine in Colonial Williamsburg's Junior Interpreter program and has never looked back.

How might one dress as an 18th-century macaroni today? Well, it certainly wouldn’t look as exaggerated as these caricatures. Revolutionary in Residence Zack Pinsent learned more about this style at the tailor shop during his February visit. Watch this conversation below.

With help from our expert trades people, Zack will be sporting a macaroni-inspired look as he hosts the Palace Green Carpet at the Garden Party. Get your tickets now to join Mr. Pinsent and Mr. Jefferson on October 2 to celebrate everything flowers and fashion.