This blog post is intended for mature audiences and contains terms and phrases that may be inappropriate for a younger audience. The language is used only in its original context and does not reflect Colonial Williamsburg's mission or values.

What risks would you take to find your family? How far would you go to help someone else find theirs?

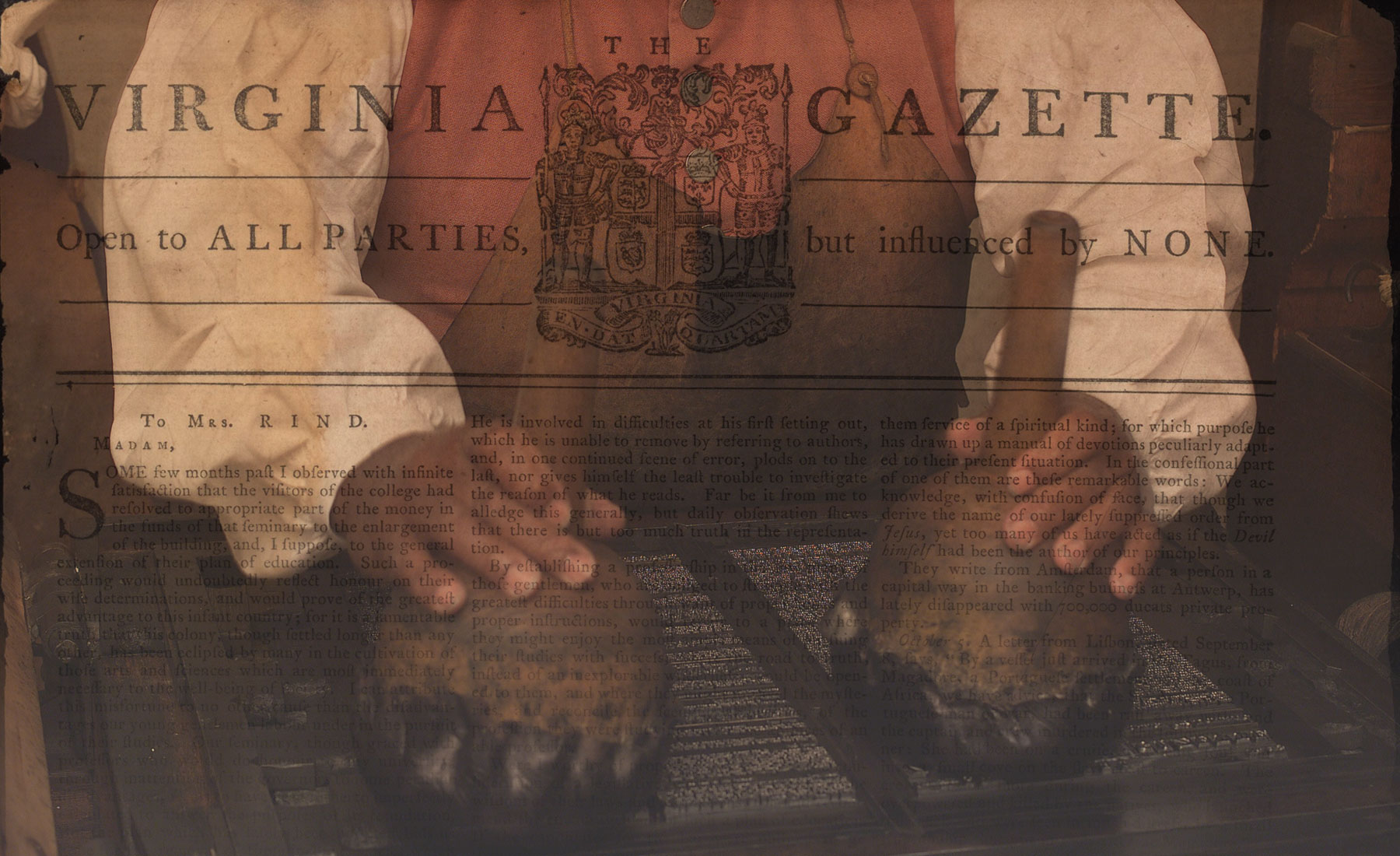

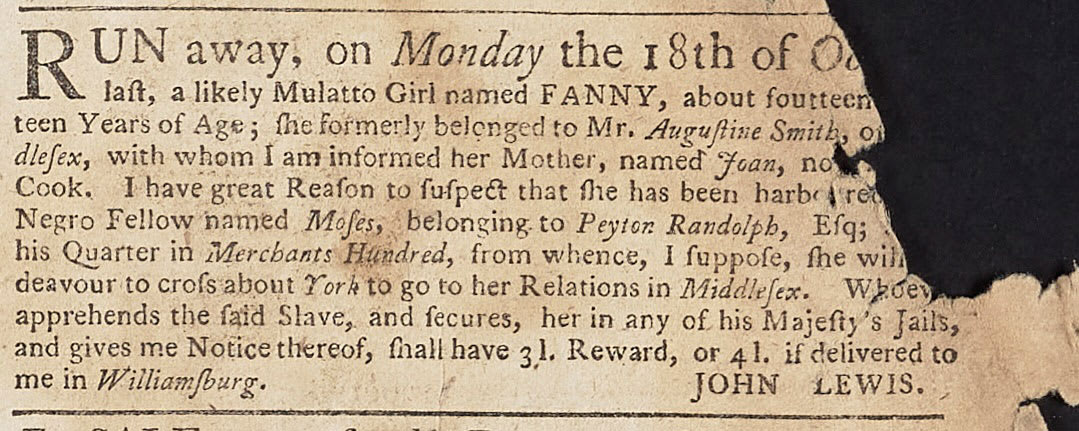

An advertisement in the January 27, 1774 issue of the Virginia Gazette describes the dramatic story of an enslaved woman named Fanny seeking her family:

RUN away, on Monday the 18th of October last, a likely Mulatto Girl named FANNY, about fourteen or fifteen Years of Age; she formerly belonged to Mr. Augustine Smith, of Middlesex, with whom I am informed her Mother, named Joan, now lives as Cook. I have great Reason to suspect that she has been harboured by a Negro Fellow named Moses, belonging to Peyton Randolph, Esq; about his Quarter in Merchants Hundred from whence, I suppose, she will endeavour to cross about York to go to her Relations in Middlesex. Whoever apprehends the said Slave, and secures her in any of his Majesty's Jails and gives me Notice thereof, shall have 3 l. Reward, or 4 l. if delivered to me in Williamsburg.

JOHN LEWIS.

In early 1774, a Williamsburg enslaver named John Lewis was seeking the return of an enslaved girl named Fanny. Lewis claimed that Fanny had escaped enslavement to search for her family, including her mother Joan. He further alleged that an enslaved man named Moses, who belonged to Peyton Randolph, was sheltering Fanny in his home. We know only a fragment of the full story of Fanny and Moses. Yet this advertisement hints at how enslaved communities in early Virginia cooperated and communicated to resist family separation.

Who Was Fanny?

Lewis’s advertisement indicates that Fanny was “about fourteen or fifteen Years of Age” in late 1773, meaning that she was born sometime around 1758 to 1759.1 Fanny had once been enslaved by Augustine Smith in Middlesex County, Virginia, north of the York River. At some point, Smith sold Fanny, separating her from “her Relations,” including her mother, Joan. Family separation was a deeply painful, but very common, experience for enslaved people.2 Sometimes younger children remained on the same property as their mothers, but older children like Fanny faced separation from their family whenever an enslaver needed extra funds. 3

On October 18, 1773, Fanny liberated herself from slavery. Perhaps hoping that she would return on her own, Lewis did not immediately place an advertisement seeking her out. But after three months, Lewis announced that he had “great Reason to suspect” that an enslaved man named Moses was harboring Fanny in his quarters on a plantation south of Williamsburg. Lewis’s advertisement offers no clues about how Lewis came to this conclusion. He might have been relying on a trustworthy informant. He could have also been following a rumor and a hunch. But based on this belief, he concluded that she was likely to cross the York River to reach Middlesex County. By anticipating her movements, he could set readers on notice. Anyone hoping to earn the reward money Lewis offered would watch for Black teenage girls crossing the York River.

Lewis’s efforts to claim Fanny were not immediately successful. This advertisement reappeared in Virginia Gazette issues published in February and March. After that, six months after Fanny’s escape, Lewis discontinued the advertisement. This might have been because he captured Fanny. Or maybe the trail had gone cold. Did she find the family she had lost?

Who Was Moses?

Moses was an enslaved man in the household headed by the wealthy and powerful enslaver Peyton Randolph. He worked as a carter, hauling goods, food, and garbage for the Randolph family. When Randolph died in 1775, white appraisers estimated that Moses was worth sixty pounds. This relatively high valuation suggests that Moses was physically capable and young enough to work.4

We do not know exactly what role, if any, Moses played in Fanny’s escape from slavery. As a carter, he had more freedom of movement than most other enslaved people.5 He could have passed messages between Fanny and her family. He might have secretly transported Fanny, hidden her, or offered her travel advice. Any of these were perilous acts. If he was discovered, Moses would be severely punished. But perhaps, like his Biblical namesake, Moses hoped to lead his people to freedom.

There is another tantalizing biographical detail about Moses. The records of Bruton Parish Church indicate that a boy named Moses, “A Basterd Son of Elizabeth Maloney By the Speakers [Peyton Randolph’s] Moses,” was born around 1767.6 A few years later, the parish register recorded the birth of a girl named Jane, the “Daughter of Elizabeth Maloney a bastard Child by the Speakers Moses.”7 Based on her surname, Elizabeth Maloney was likely a white woman, probably of Irish heritage.8

If that is correct, these baptismal records document an ongoing sexual relationship between a white woman and an enslaved man of African descent. This was dangerous in colonial Virginia. A 1691 law promised brutal consequences for interracial sex. If an “English woman . . . shall have a bastard child by any negro or mulatto,” she faced a hefty fine and her child would be forced to serve the church until they were thirty.9 There is no evidence that government authorities enforced this law against Elizabeth or her children Jane and Moses. They might have escaped the law’s notice. But perhaps Moses’s precarious family life led him to sympathize with Fanny’s dreams of reunion.

Questions

Lewis’s advertisement in the Virginia Gazette records a mix of fact and speculation. He was likely correct about certain details, like the date Fanny fled. But in other parts, like Fanny’s route of escape, he was making an informed guess. Lewis combined some unknown information with his understanding of Fanny’s family and his knowledge of eastern Virginia geography to create a plausible scenario.

But Fanny might have misdirected Lewis. Or his information might have been mistaken. In addition to these uncertainties are many more about what happened next. Did Fanny remain free? Did Joan ever see her daughter again? Did Moses face punishment or greater scrutiny? How did Peyton Randolph, at the peak of his political career, react to the printed accusation that Moses was assisting Fanny’s escape?

The story of Fanny and Moses is frustratingly incomplete. But even so, it offers us a rare window onto a largely unknown world of cooperation and liberation. We know that enslaved people assisted one another in fleeing slavery and finding family. Yet we also know that anyone engaging in this work would have sensibly hidden their role from the glare of white observers. Surviving historical documents, usually written by white men, therefore rarely document this hidden world. Sometimes, to find these untold stories of bravery and resistance, we must look underground, to the silences that lie beneath the historical record.

Watch the Video

Learn More

Sources

- Lewis likely did not know Fanny’s exact birthday, or even her birth year. She might not have known her precise age either. Born decades after Fanny, the abolitionist Frederick Douglass remembered in his autobiography that he had “no accurate knowledge of my age,” since “most masters . . . keep their slaves thus ignorant. I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday.” Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself (Boston: 1845), 1, link.

- Brenda E. Stevenson, Life in Black and White: Family and Community in the Slave South (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 161; Allan Kulikoff, Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680–1800 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1986),358–64; John J. Zaborney, Slaves for Hire: Renting Enslaved Laborers in Antebellum Virginia (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2012), 11–12.

- Kulikoff, Tobacco and Slaves, 359; Philip D. Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake and Lowcountry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1998), 514.

- The median valuation of enslaved people in Randolph’s estate inventory was 30 pounds. The average was about 48 pounds. “Peyton Randolph Historical Report, Block 28 Building 6 Lot 207 & 237,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library.

- Graham Hood, The Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg: A Cultural Study (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1991), 252–53; Philip D. Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake and Lowcountry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1998), 56–57.

- “Bruton & Middleton Parish Register 1662-1797,” Bruton Parish Historic Records, page 52.

- “Bruton & Middleton Parish Register 1662-1797,” Bruton Parish Historic Records, page 55.

- Sharon Block, Colonial Complexions: Race and Bodies in Eighteenth-Century America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 99.

- William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619 (New York: R. & W. & G. Bartow, 1823), 3:87, link.