Have you ever felt that you were being followed?

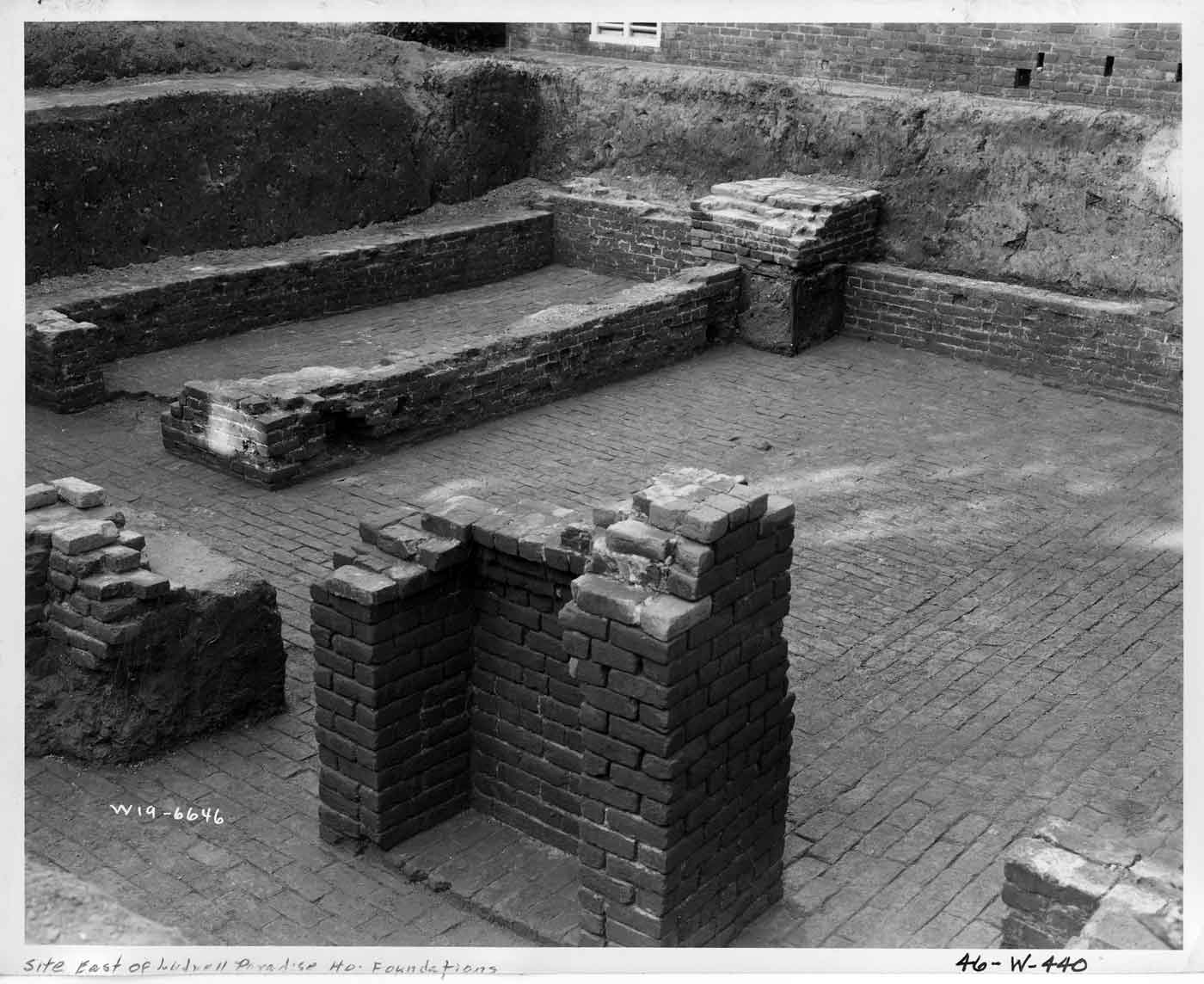

Born into slavery around 1815, Edmond Parsons would have been 200 years old the summer we met — he as the former resident of a 19th-century house on Duke of Gloucester Street, and I as an archaeologist uncovering its chimney. For the next five years, wherever the crew excavated, Edmond Parsons seemed to have a connection. He was enslaved for nearly 50 years on the Robert Carter property, the site of our 2018 archaeological field school (pictured above). When we turned our attention to the First Baptist Church site in 2020? You guessed it: Edmond Parsons was among the church’s nineteenth-century deacons.

Then, Parsons began tinkering with my Internet searches. First-person accounts — glimpses into his life — spilled out onto pages of court testimony, and in an interview before Congress. Of course, this makes the research sound easier than it was. Edmond Parsons was hidden from me for a long time. A lucky break revealed his name, and the details of his amazing story have emerged slowly. Each new discovery feels like a gift from Parsons to me — and now to you.

The Saunders, one of Williamsburg’s oldest and wealthiest families, enslaved Edmond Parsons. Robert Saunders, Sr. practiced law. Robert Saunders, Jr., who inherited Edmond upon his father’s death in 1835, taught mathematics at the College of William and Mary, and held positions as the College’s president, a Virginia State Senator, mayor of Williamsburg, and the director of the “Eastern Lunatic Asylum.” Within this high-profile household, Edmond Parsons served as the butler.

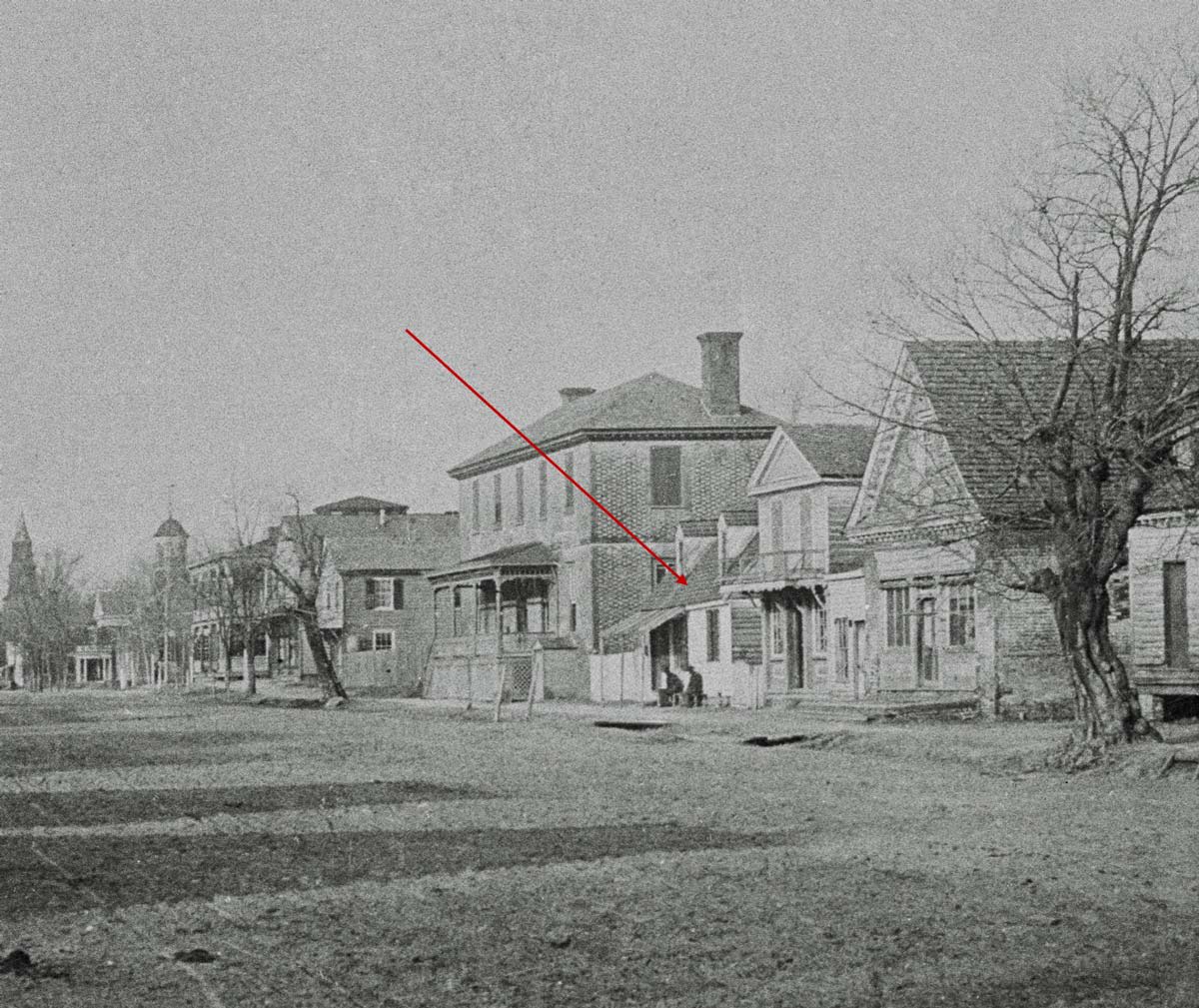

In 1837, six years after Nat Turner’s Rebellion, and during one of the most repressive periods in American slavery, Edmond Parsons received written permission to travel to Norfolk to marry Margaret (Peggy) Moss. Twenty years Edmond’s senior, Peggy had been freed in 1836 by the will of her former enslaver, Thomas Griffin. That same will left Peggy with $500, which she invested in the purchase of a frame house on Duke of Gloucester Street, between the Ludwell-Paradise House and the Prentis Store.

Edmond continued to labor, and likely to live, on the Saunders property, but he invested time, labor, and money in the repair and upkeep of Peggy’s house. Over a period of 20 years, “by the united exertions of himself and his wife . . . they put their home in a very comfortable order.” But if Edmond regarded this as their joint property, the 1860 Federal Census tells a different story. That document lists Margaret Parsons (age estimated at 90) as the free Black owner of this house, living with Julia Minson, who the census identifies as a 16-year-old mulatto seamstress. There is no mention of Edmond Parsons in Williamsburg.

But Edmond was there. In 1862, as the Civil War closed in on Williamsburg, Robert Saunders evacuated the town with his family, leaving Parsons behind to guard the house and library. On May 5, a neighbor reported that Union soldiers had broken into the Saunders’ house and were making off with the books. She provides an eye-witness account of Edmond’s presence: “I asked Edmond Parsons (Mr. Saunders’s butler) to help me save his Master’s books, but he declined, was afraid to meddle-all bosh, a good for nothing, ungrateful wretch.” [i]

The Emancipation Proclamation altered Parsons’ worldview. His manner of introduction reflected this shifting self-perception: “I have been a slave from my childhood up to the time I was set free by the emancipation proclamation.” At 50 years old, Edmond Parsons was starting again, confident in the power of legislation to make him a free man. But personal loss would soon discourage that confidence.

Peggy Parsons died in January 1865. In the days that followed, Edmond was unceremoniously evicted from their house. He recounts the event in a later interview: “I had a house where I had been living for 20 years. A lawyer there went and got the provost marshal to send a guard and put me out of my house. They broke my things up, and pitched them out, and stole part of them.” Peggy’s half-sister, Monimia Minson (possibly Julia Minson’s mother), was the instigator. Challenging the legality of Edmond and Peggy’s 1837 marriage, she claimed rightful ownership of her sister’s property. Newly emancipated and recently widowed, Edmond now found himself homeless.

His fragmentary story picks back up a year after Peggy’s death. In January 1866, Parsons travelled to Washington, D.C. to attend a freedman’s rights convention, joined by Alexander Dunlop, a free blacksmith from Williamsburg, Thomas Bain (a dentist), Richard Hill, Madison Newby (a farmer), Rev. William Thornton, and Dr. Daniel Norton (a physician). These men represented Black communities in Norfolk, Hampton, Yorktown, and Williamsburg, and Edmond Parsons’ inclusion suggests that he was highly esteemed by his peers.

Before returning to Williamsburg, this Washington travelling party secured individual invitations to testify before the Joint Congressional Committee on Reconstruction. These were rare invitations. The Committee conducted a mere 137 in-person interviews to assess the existing political and social climate in former Confederate States (Robert E. Lee was interviewed two weeks after Edmond Parsons). Only seven Black citizens — Parsons and his travelling companions — offered their testimonies. Edmond was one of four men who had endured slavery.

Senator Jacob M. Howard of Michigan interviewed Edmond Parsons on February 3, 1866. The transcript reveals Parsons’ answers to questions about his background, treatment during and after the Civil War, and future plans. He spoke of education as a commodity that the Black community was “anxious for” and “felt grateful for,” and used his interview to report the “bad treatment [he] received” when evicted from his house.

Back in Virginia, Edmond Parsons registered to vote in 1867. His name appears in the Poll Book for James City County’s “First Magisterial District: Colored Voters” as the 147th in an alphabetical listing of the county’s first 225 Black voters.

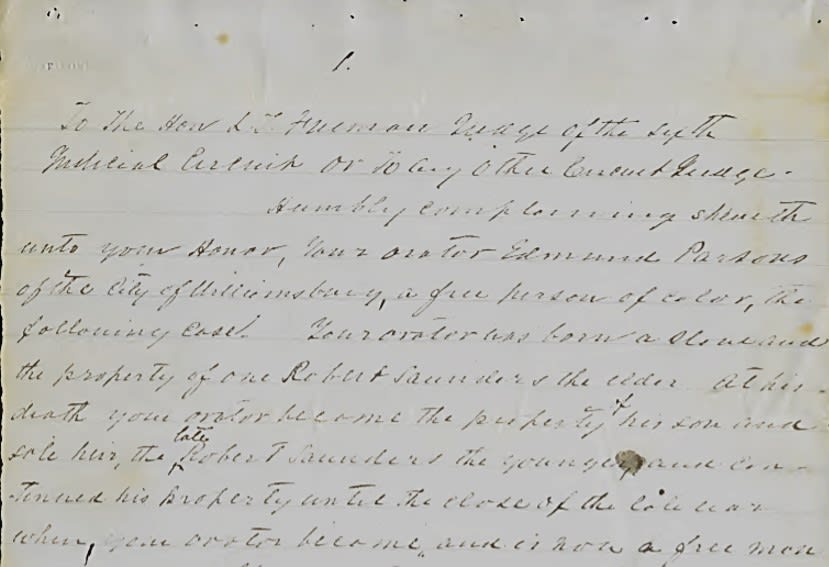

In 1870, Parsons exercised another new right when he brought the case of Edmond Parsons versus Monimia Minson before a circuit judge in Chancery Court. In eight pages of testimony, Parsons argued eloquently and persuasively for ownership of the house that he shared with Peggy, making these points: Enslaved at the time that their house was purchased, he was prevented from owning property. Peggy had been their purchasing agent and, while only her name appeared on the deed, thirty years of marriage should entitle him to inherit Peggy’s property. He responded to Monimia Minson’s challenge to the legality of that union by citing the 1866 Cohabitation Law which afforded enslaved people cohabitating as husband and wife before emancipation the same rights and privileges as those who were married by law.

Despite sound argumentation, Edmond did not win the case. In 1874 he revived it, this time asking only for compensation for expenditures made toward the repair and improvement of the premises. By this time, Monimia Minson was dead, and there is no evidence that the case was ever settled.

Parsons’ situation recalls the testimony of another witness interviewed by the Joint Committee on Reconstruction—a white Baptist preacher from Fredericksburg:

“. . . the testimony of the negroes will not be worth a snap of your finger. . . . A negro can come and give his testimony, and it passes for what it is worth with the courts. . . . There are the judges, the lawyers, and the jury against the negro, and perhaps every one of them is sniggering and laughing while the negro is giving his testimony.”

Was this Edmond Parsons’ experience? We know he lost the house. The 1880 Census shows Julia Minson as its owner and, in a codicil to her will dated 1882, the house was among the assets she distributed.

I often wonder what happened to Edmond Parsons. About a year ago, I discovered this in the Minutes Book for the First Baptist Church:

“Sept 8th 1895. Dea[con] Edward Parsons.

The above Bro[ther] was a faithful servant of Christ from his connection to the leh [lay] which was before the last War to the day of his death.”

The description is accurate, but the name is not. If this is Edmond Parsons, he lived to be 80 years old. Did he outlive the friends who knew his name and his story? Not everyone born into slavery spoke their truth before a Congressional Committee. Not everyone embraced the post-emancipation world with such tenacity and unflagging optimism.

Edmond Parsons’ story fascinates me. I am drawn to its messiness and its complications. It continues to teach me. I have spent unnecessary time trying to identify “good guys” and “bad guys,” and have ultimately concluded that the characters in this story — Edmond, Peggy, Monimia, and Julia — were all doing the best they could to make a new start and eke out a better life. There was not a lot to go around.

Naively, I have always thought of emancipation as an event. Whether received on January 1, 1863 with the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation or on June 19, 1865 when word finally reached thousands ensalved in Galveston, Texas, emancipation, surely, was transformative. Or was it? Edmond Parsons has spent the last several years showing me emancipation’s complicated reality, and the variety of ways in which those who were freed remained in bondage. Even now.

For all that Edmond Parsons has revealed to me, I still have questions: Where did he live after losing his house? How did he use his 30 years of freedom? Where is he buried? I look for new pieces of his story everywhere I go. Recently, Edmond has been pointing me in the direction of a woman named Zizi Parsons. Described as a free person of color and a “baker of cakes,” Zizi owned land and a house (known today as the Richard Crump house) on Francis Street. In 1837 she left that property to Peggy Parsons. Was it intended for Edmond?

I trust that I have not heard the last from Edmond Parsons. Our paths have been too entangled these last five years to unravel now.

Meredith Poole has been a Staff Archaeologist at Colonial Williamsburg for 35 years. Her career started with the 1985 excavation at Shields Tavern and has continued through more recent projects at Charlton’s Coffeehouse, the Public Armoury, and the Market House. Meredith has shared her enthusiasm for archaeology in a variety of forms: managing the Reconstruction Blog, leading archaeological walking tours along Duke of Gloucester Street, overseeing the Kids Dig on Duke of Gloucester Street, and is presently leading the First Baptist Church excavation.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.