What did freedom mean to John Harris? As the enslaved attendant for Peyton Randolph, Harris was a personal witness to the early stages of the American Revolution in Virginia. Randolph was one of the continent’s most prominent revolutionaries, presiding over the Virginia House of Burgesses, the Continental Congress, and the Virginia Convention. He was at the center of revolutionary politics and so, as a result, was John Harris. Accompanying Randolph almost everywhere he went, Harris likely overheard many dangerous conversations between the revolutionaries.1 As he listened and learned in rooms and hallways that few other enslaved people entered, Harris probably developed a more intimate understanding of the American Revolution than we ever could today.

Harris had accompanied Peyton Randolph to Philadelphia for the Second Continental Congress. After Randolph died in October 1775 in Philadelphia, Harris returned to Virginia with Randolph’s widow Elizabeth.2 They arrived in Williamsburg just as many enslaved people were escaping slavery in response to Governor Dunmore’s offer of freedom to enslaved people who would join him in fighting the rebels. But Harris remained, for the moment. Randolph’s will gave “my man Johnny” to his nephew Edmund Randolph.3 Edmund was a young man on the rise, soon to be chosen as the mayor of Williamsburg and the Attorney General of Virginia.4

Two years later, Harris emancipated himself. Unlike many other fugitives from slavery in revolutionary Virginia, Harris did not seek freedom with nearby British forces. Instead, Harris fled slavery when Britain’s armies were massed in the northern colonies. In December 1777, Edmund Randolph placed an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette seeking his return:

Williamsburg, Dec. 10, 1777.

I will give a reward of five dollars, besides what the law allows, to any person who will apprehend Johnny, otherwise called John Harris, a mulatto man slave who formerly waited upon my uncle, the late Peyton Randolph, Esq; and secure him, so that I may get him again. He took with him, when he went away, a green broadcloth coat, and a new crimson waistcoat and breeches, a light coloured Bath coating great coat, a London brown Bath coating close bodied coat, a pair of old crimson cloth breeches, and some changes of clothes. He is about five feet seven or eight inches high, wears straight hair, cut in his neck, is much addicted to drinking, has gray eyes, can read and write tolerably well, and may probably endeavour to pass for a freeman. The above reward of five dollars will be given if he is taken in Virginia, but five pounds, besides what the law allows, will be paid to any person who apprehends him out of Virginia, and conveys him to me.

Edmund Randolph

Less than two hundred words long, this advertisement doesn’t tell us nearly as much as we would like to know about Harris. But when read carefully, it offers some fascinating clues, perhaps more than its author meant, about how Harris might have experienced this revolutionary era.

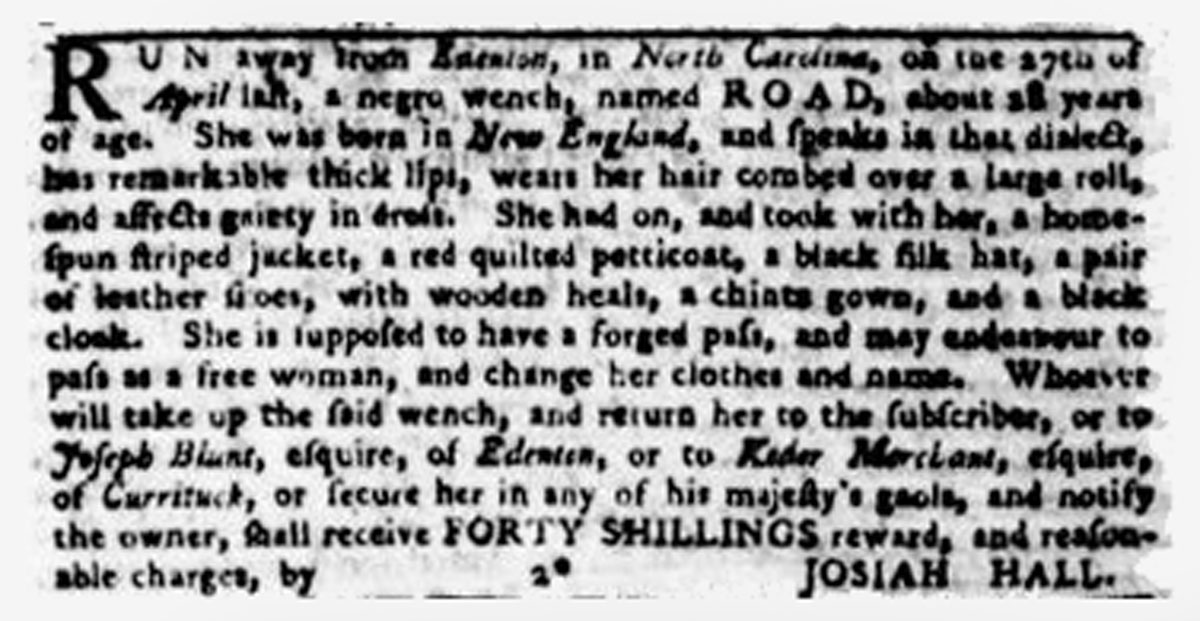

Learn more: The Virginia Gazette can offer one of our best guides to understanding the lives of enslaved people in eighteenth-century Virginia.

Waiting Man

John Harris, a mulatto man slave who formerly waited upon my uncle, the late Peyton Randolph, Esq.

In the late eighteenth century, members of Virginia’s gentry often relied on personal attendants. There were several terms for this role, including “waiting man,” but many enslavers simply referred to their attendant as “my man.” As Peyton Randolph’s attendant, Harris’s responsibilities might have included caring for his enslaver’s clothes, dressing him, and assisting with service in the dining room.5 Records indicate that Harris also did errands around town for Randolph, including at the printing office and the Governor’s Palace.6 Afforded greater freedom of movement than most enslaved people, Harris had the opportunity to learn about how to navigate white society. His journey to Philadelphia might have also taught him about intercolonial travel. This knowledge would have been useful for a fugitive from slavery.

Clothing

He took with him, when he went away, a green broadcloth coat, and a new crimson waistcoat and breeches, a light coloured Bath coating great coat, a London brown Bath coating close bodied coat, a pair of old crimson cloth breeches, and some changes of clothes.

Advertisements seeking self-emancipated enslaved people usually identified them by clothing. While many enslaved people wore simple, unadorned clothing, waiting men for wealthy families like Harris dressed in elaborate uniforms known as livery, which displayed their enslaver’s wealth and power. These outfits featured bright, contrasting colors, often based on the colors in the enslaver’s family coat of arms.7 Edmund Randolph’s advertisement for Harris suggests that he escaped wearing a three-piece livery uniform, consisting of crimson breeches, a crimson waistcoat, and a green overcoat. It is possible that during his escape Harris wore his livery when he wanted to be seen as an enslaved attendant running errands and used the “changes of clothes” mentioned in the advertisement when he judged it safer to pass as a free man. 8

Alcohol

He is about five feet seven or eight inches high, wears straight hair, cut in his neck, is much addicted to drinking…

Virginia enslavers attempted to control drinking among enslaved people. While they sporadically served alcohol to enslaved people during seasonal holidays, they usually prohibited unsupervised drinking at other times. Enslavers feared that habitual drunkenness could lead enslaved people to resistance, theft, and lower productivity.9 Describing Harris as “much addicted to drinking,” Randolph’s advertisement suggests that Harris may have begun to challenge Randolph’s authority prior to his escape by secretly consuming alcohol.

Waiting men like Harris sometimes faced accusations of illicit drinking.10 This may have been because their role allowed them to move around town, which made acquiring liquor much easier. Or it may be that waiting men were simply closer at hand, and easier to find fault with, than other enslaved people. While the historical record contains many accusations about enslaved peoples’ drinking, we lack accounts that would help us to understand what alcohol meant to enslaved people like Harris. What looked like a dangerous addiction to Randolph might have simply been a way for Harris to cope with the daily brutality and terror of enslavement.11 Drinking could have also been a way to assert independence and challenge Randolph’s control of his life.12 Or, very possibly, Randolph might have been exaggerating.

Literacy

. . . can read and write tolerably well, and may probably endeavour to pass for a freeman.

Edmund Randolph’s advertisement indicates that Harris was literate. This was somewhat uncommon. In the 1770s, about one of every twenty “runaway” advertisements in the Virginia Gazette noted that an escaped enslaved person was literate.13 If Harris planned to “pass for a freeman,” as Randolph predicted, literacy would have been useful. It could have allowed Harris to forge freedom papers and find skilled work.

Escape

The above reward of five dollars will be given if he is taken in Virginia, but five pounds, besides what the law allows, will be paid to any person who apprehends him out of Virginia, and conveys him to me.

Virginia law rewarded anyone who captured self-emancipated people. Many enslavers, including Randolph in this case, offered additional incentives. Those seeking such rewards could challenge an unaccompanied Black traveler to prove that they were either free or authorized to be away from their enslaver. If they were unable to prove this, they would either be returned to their enslaver or jailed.14 Fugitives from slavery faced a dangerous choice. Knowing that encounters with white people could be dangerous, some took refuge in nearby woods and swamps, often returning after a brief period of truancy.15 Others risked recapture and attempted to reach distant cities where they could pass as free. Because governments across the continent protected slavery at this time, it was nearly impossible for self-emancipated people to seize full, legal freedom through escape.

We don’t know Harris’s intended destination. Edmund Randolph believed that Harris might “pass for a freeman” and offered a substantial reward for anyone returning Harris from “out of Virginia.” This doesn’t prove that Harris left Virginia, but it does suggest that Randolph recognized that Harris possessed the intelligence and experience to journey long distances in pursuit of his freedom.

Unlike other “runaway” advertisements for escaped waiting men, Randolph’s notice does not indicate that Harris escaped with a horse. This would have limited his options. Did he intend to travel by water? He might have attempted to reach a city to blend in with its free Black population. Perhaps he hoped to return to Philadelphia. If that was his intention, he faced a hard road. The winter of 1777 to 1778 is remembered for the pain it inflicted on George Washington’s ill-equipped Continental Army, which arrived at Valley Forge about a week after Edmund Randolph’s advertisement appeared in the Virginia Gazette. If Harris went north in search of freedom, he might have endured similar hardship on his way.

Absences

Reading Edmund Randolph’s advertisement for John Harris tells us about his physical appearance, his clothing, his literacy, and parts of his background. But it also raises many questions. Why did Harris flee when he did? Where did he go? Was his escape successful? There is no evidence to suggest that Harris ever returned to the Randolph family. Like other self-emancipated people, it is possible that he was captured and sold back into slavery. It is also possible that he reached freedom. There is no trace of Harris in the historical record after 1777.

While the end of Harris’s story is uncertain, its trajectory was extraordinary. A silent witness to the early stages of the American Revolution, he soon found that the freedom his enslavers sought was not for him. As the revolution unfolded around him, he fled into the unknown and never returned.

WATCH THE VIDEO

Learn More

Sources

- Enslaved waiting men sometimes had access to private and government spaces where important political and legal matters were discussed. In 1749, for example, an enslaved South Carolina man named Agrippa explained to a group of other enslaved people that he “knew how to go before Gentlemen” because he “had waited before on his Master in the Council Chamber, and was used to it.” Quoted in Bertram Wyatt-Brown, “The Mask of Obedience: Male Slave Psychology in the Old South,” in J. William Harris, ed., Society and Culture in the Slave South (New York: Routledge, 1992), 144. See also discussion of this episode in Philip D. Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake and Lowcountry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1998), 460; Douglas Walter Bristol, Jr., Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 15.

- Elizabeth Randolph’s return to Williamsburg is noted in the Williamsburg section of Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), Nov. 9, 1775, p. 3, link.

- In fact, the will gave Edmund Randolph with Harris only “after the Death of my wife.” However, given that Edmund’s advertisement seeking Harris was dated only two years later, it is likely that Elizabeth provided Harris to Edmund earlier. “Will of Peyton Randolph,” in “Peyton Randolph House Historical Report, Block 28 Building 6 Lot 207 & 237,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library.

- John J. Reardon, Edmund Randolph: A Biography (New York: Macmillan, 1975), 36.

- Susan A. Kern, The Jeffersons at Shadwell (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 101.

- In 1765, “Johnny” is recorded picking up “1 stick best Dutch sealing wax” for Randolph. See November 1765 entry in Virginia Gazette Daybooks, 1750–1766, Tracy W. McGregor Library Accession #467, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va., link. Governor Botetourt’s butler William Marshman tipped Harris and described him as the “Speaker’s Man” in 1769. “Enslaving Virginia,” 638.

- Kern, Jeffersons at Shadwell, 97, 101; Bristol, Knights of the Razor, 15, 22; Linda Baumgarten, “Clothes for the People: Slave Clothing in Early Virginia,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library, p. 7.

- An enslaver named Thomas Gaskins wrote in an advertisement seeking David, his “cunning” waiting man, that he believed that he will “swap his Clothes as may suit him.” Thomas Gaskins advertisement for David, Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Nov. 19 1772, p. 4, link.

- Advertisements in the Virginia Gazette often suggested that enslaved people drank without their approval. For example, an advertisement seeking an escaped “mulatto servant man, named John Newton,” which notes that he “shaves and dresses well, but is much addicted to liquor.” See Virginia Gazette (Purdie), July 19, 1776, p. 4, link. See also advertisement for Ben Harwood, whom Robert Skipwith described as “very much addicted to drunkenness.” See Virginia Gazette (Purdie), July 10, 1778, p. 3, link. In 1709, enslaver William Byrd wrote in his diary, “I reproved George for being drunk yesterday.” Louis B. Wright and Marion Tinling, eds., The Secret Diary of William Byrd of Westover, 1709-1712 (Richmond: Dietz Press, 1941), 56. Sarah Elizabeth King Pariseau, “Powerful Spirits: Social Drinking in Eighteenth-Century Virginia,” (M.A. Thesis, College of William & Mary, 2006), ch. 1.

- The diary of a Virginia enslaver and plantation owner named Landon Carter, for example, describes a lengthy struggle against the drinking of his attendant Nassau. In 1768, Carter placed an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette seeking a replacement for “My man Nassau” who had “fallen into a most abandoned state of drunkenness.” Virginia Gazette (Rind), March 3, 1768, p. 3, link. On Carter and Nassau, see Rhys Isaac, Landon Carter’s Uneasy Kingdom: Revolution and Rebellion on a Virginia Plantation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), ch. 13. On alcohol and waiting men, see Bristol, Knights of the Razor, 21–22.

- Bristol speculates that for waiting men like Nassau or Harris, drinking alcohol may have been a way to escape the tension caused “by the disparity between having to be adroit and confident and then having to display the self-effacement demanded by their masters.” Bristol, Knights of the Razor, 22.

- Pariseau, “Powerful Spirits,” 27–31.

- Among waiting men and other skilled enslaved people, about one in ten “runaway” advertisements mentioned literacy. Antonio T. Bly, “‘Pretends he can read’: Runaways and Literacy in Colonial America, 1730—1776,” Early American Studies 6, no. 2 (Fall 2008): 267, 279–80; Bristol, Knights of the Razor, 21. Advertisements for enslaved waiting men noting their literacy include the following: James Mercer’s advertisement for Christmas in Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), March 19, 1772, p. 3, link; William Roane's advertisement for Joe in Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Aug. 17, 1769, p. 3, link; Thomas Gaskins advertisement for David, Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Nov. 26 1772, p. 4, link.

- William Waller Hening, ed., Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, From the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619 (Richmond: Franklin Press, 1819), 6:362–66, link.

- Marcus P. Nevius, City of Refuge: Slavery and Petit Marronage in the Great Dismal Swamp, 1763–1856 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2020), ch. 1, 20-37; Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998), 120 –21.