Work on the restoration of 18th-century Williamsburg was barely underway and Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin had a problem. Local residents were criticizing interior colors and furniture selections because they were all being decided upon by “Northerners.” Some even dubbed the start of the restoration work as a “Yankee invasion.”

Many aspects of the archaeological investigations, reconstructions, and restorations involved significant change for area residents. Businesses, churches, municipal buildings, and family homes had to be relocated or torn down. Parts of the town’s 19th and early 20th-century architectural and landscape features disappeared to the consternation of some residents. Many felt the town they knew and loved would be lost.

Goodwin knew that taking “sufficient care… to secure the southern point of view” would help to inspire public confidence in the project. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller also expressed the conviction “that this interior decoration, including such matters as paint, paper, furnishing and hangings etc. should be done so as to give a distinct southern atmosphere.”

While an all-male Advisory Committee of Architects periodically visited Williamsburg to critique the progress of architectural restoration work in the 1930s, a group of female counterparts also played a role in guiding the decision-making process, particularly regarding interior décor and furnishings.

This was the Ladies Advisory Committee. Overseen by interior decoration consultant Susan Higginson Nash, the only woman working in the architects’ office, the committee consisted of women from Williamsburg, Richmond, and surrounding counties, many of whom lived in historic houses themselves.

In an oral history Nash recalled her thinking. “I realized when I started working on the Raleigh that I was, after all, from the North, and there was a certain amount of – well, not exactly antagonism, but lack of enthusiasm. Why should a Northern woman come down to do furnishings and painting that any Southern woman could do just as well?”

Nash approached George and Mary Haldane Coleman of Williamsburg with the idea of involving a group of local women to underscore the architectural team’s desire to listen to and seek input from local Virginians. The Colemans served as liaisons between Nash and local women, making initial overtures and paving the way for formal introductions.

Nash submitted a final list of Ladies Advisory Committee members on October 2, 1930. It was divided into several subcommittees, each with its own chair: the Williamsburg Ladies, chaired by Mary Haldane Coleman; Ladies from Neighboring Plantations, chaired by Mrs. Otway Byrd; the Richmond Ladies, chaired by Mrs. E.M. Crutchfield, with the governor’s wife, Grace Pollard, serving as honorary chair; and the Richmond Junior League, chaired by Elizabeth Cocke.

The first Ladies Advisory Committee meeting, held on October 22, 1930 at the Williamsburg office of Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, the architectural firm guiding the restoration, provided the women with an overview of projects in process. They examined models of the Capitol foundations and proposed Capitol reconstruction and then commenced a tour of several building sites, including the Wren Building, the Ludwell-Paradise House, and the Raleigh Tavern.

The women discussed paint colors, light fixtures, and other elements at the sites and as a group expressed overall approval with the accuracy of the work. They then adjourned for tea at the Lady Travis House restaurant and further discussion.

The second meeting on November 25 was larger, as it included a contingent of women from Richmond and surrounding plantations. They met at the Raleigh Tavern and began by examining the arrangement of furnishings in the different rooms. Marion Carter Oliver of Shirley Plantation noted a disproportionate pineapple over the mantel in the Minerva Room (now known as the Daphne Room) and suggested using a pineapple in the drawing room of Shirley Plantation as a model. Mr. Perry agreed.

As they continued through the building several ladies expressed interest in getting sample paint colors or in copying elements of the furnishings. Their appreciation of the research work which had preceded restoration of the buildings grew as they toured the James Geddy House (then known as the Neal House), the Coke-Garrett House (at that time the Van Garrett House), the Wren Building, and the Governor’s Palace excavations. They even stopped inside the Williamsburg High School to examine archaeological artifacts uncovered during the Palace excavations.

By April 1931, the Ladies Advisory Committee’s admiration of the restoration project had grown to the point that Mary Haldane Coleman submitted a letter of gratitude to John D. Rockefeller Jr. on behalf of the entire group. She complimented “the limitless care and the flawless taste your architects are perfecting at Williamsburg, in design, in gardening and in interior decoration.”

Mrs. Coleman concluded by acknowledging the accomplishments of the Williamsburg Restoration, noting “it has done such immense and reverent research in establishing the actual topography of the old town; it has procured for Williamsburg so many treasures, that we have ceased to look on the work as simply a restoration. It has become a model of manners and methods.”

Bearing the signatures of all of the members of the Ladies Advisory Committee, the letter offered assurance that the goal set out with the formation of the committee had been reached. The local community had embraced the project, understood its far-reaching impact, and was eager to cooperate.

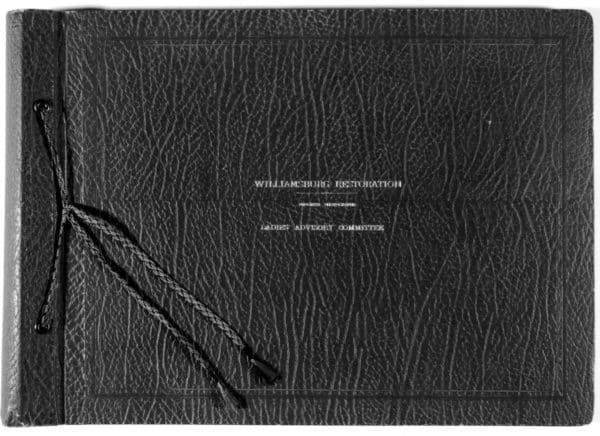

As a gesture of thanks to the committee, the Williamsburg Holding Corporation presented each member with an album of restoration progress photographs at the November 2, 1932 meeting. One of these albums now resides in the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library. It features photographs of the different buildings the group toured and discussed, from the Raleigh Tavern and Capitol to the Governor’s Palace and Market Square Tavern.

Mrs. Crutchfield of the Richmond Ladies Committee called the presentation of the albums “the key-note of the day… I know that more than one of us, seeing for the first time those noble buildings and realizing what they meant to Virginia, could not speak for tears.”

As the first stage of the restoration work wrapped up, Perry, Shaw & Hepburn reoriented their business focus to Boston and the Ladies Advisory Committee, in the words of architect Singleton P. Moorehead, died a “natural death.”

The women disbanded after gathering for a few more teas and lively discussions at the Travis House restaurant. However, the committee’s influence continued to be felt, as the women spread the word about the authenticity of the research and reconstruction work happening in Williamsburg to friends and family. Their trust led many to visit the exhibition buildings as they opened and to become the first of many generations of guests to delight in all that Colonial Williamsburg has to offer.

Marianne Martin is a Visual Resources Librarian at the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library at Colonial Williamsburg. She works behind the scenes to care for the historical images housed in the library and assists both Colonial Williamsburg staff and outside researchers with locating visual materials to support their projects. The opportunity to learn more about the people, places, and events featured in the large collection of historical photos leads to fascinating detective work and new discoveries each day. When she first visited Colonial Williamsburg on an eighth grade class trip, little did she know that she would one day have the privilege to work at the museum!

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.