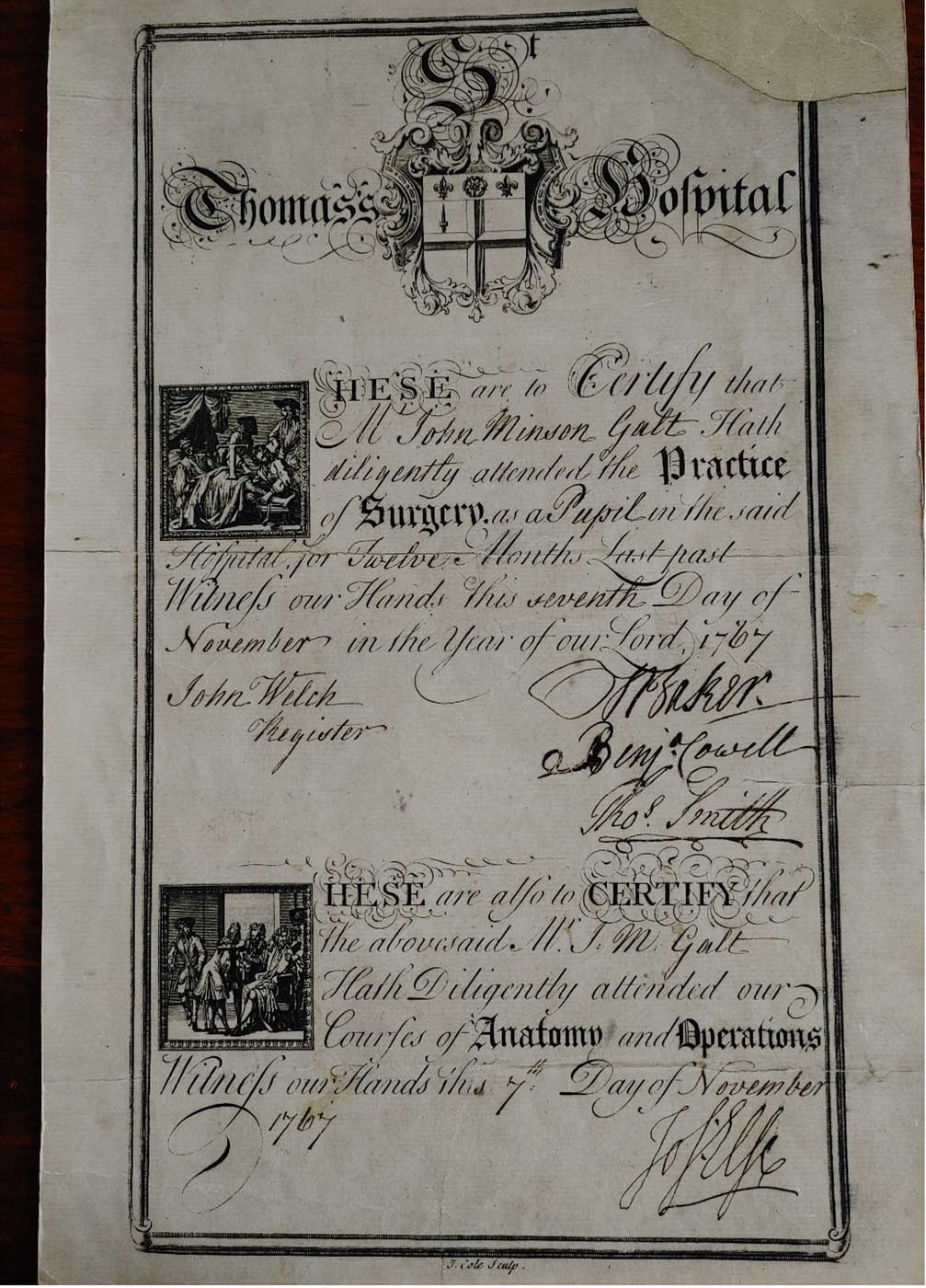

In the 18th century, it was not possible to obtain a degree in pharmacy or surgery. The traditional method for studying these disciplines was through an apprenticeship, and some students pursued additional training in London hospitals. Based on surviving records, it appears that John Galt apprenticed with Dr. William Pasteur in Williamsburg. We know that Galt also traveled to London because his certificate for 12 months of study at Saint Thomas’s Hospital has survived. Pasteur also studied at St. Thomas’s and may have influenced Galt attend there as well.

Saint Thomas’s Hospital was already a historic institution by the 18th century. Its early origins can be traced to a 12-century Augustinian infirmary. There were several other hospitals in London that Pasteur or Galt could have chosen. Saint Bartholomew’s was founded 1123 and today is the oldest hospital in London. Guy’s Hospital opened in 1721 for the treatment of lunatics and patients deemed incurable. The Middlesex Hospital medical school opened in 1746 and added beds for maternity patients the following year, which was an innovative idea at the time.

Studying at London hospitals was expensive. In addition to travel expenses, lodging, and food, there was also tuition and related expenses. In 1775, James Ware noted in his diary that he paid 49 pounds, 10 shillings, and 6 pence to study for a year at St. Thomas’s and Guy’s. “For his tuition he paid £25, 4s to St Thomas’ Hospital, and in addition eight guineas to Mr Else for anatomy and instruction in the dissecting-room, £1, 2s to the surgeryman, one guinea for a share of muscular subject to dissect, 2s, 6d for the cleaning of the anatomy theatre and one guinea to Mr. Whitfield, secretary of the medical school, who was also the apothecary. He also paid fees to Guy’s — two guineas to Dr. Saunders and ten guineas for midwifery.”

The medical school at Saint Thomas’s was organized in the early 18th century and featured an operating theater. Unfortunately, the latter has not survived. The traditional style of an operating room was like a theater but without seats. A series of semicircular elevated tiers provided standing room only and students looked down into a central viewing area to observe a surgeon demonstrate his skill. Patients were either strapped or held in place on a table while the procedure was quickly performed without anesthesia or sterilization.

Saint Thomas’s also had facilities for teaching anatomy and performing dissections. Period resources for teaching anatomy included articulated skeletons, and wet and dry specimens. A variety of anatomy textbooks feature illustrations of artistically drawn skeletons highlighting bones and muscles as well as the nervous and circulatory systems.

Dry specimens such as a preserved limb were used to teach muscle structure. A variety of colored waxes were injected into the blood vessels of the specimens to highlight the circulatory system. Extant texts list the formulas for creating the colored wax.

There was also an avid interest in teaching pathology by preserving a variety of specimens in a solution and storing them in clear glass jars. What has not survived are the propriety formulas for creating the solutions. One clue can be found in the definition of the word alcohol in an 18th-century medical dictionary. It states that the highly distilled product was used to preserve specimens. The product called alcohol was not defined by proof, but by the distillation method.

In addition to teaching students, the hospital provided care for the sick poor as well as those with venereal disease. In the early 18th century the hospital had 19 wards with a capacity for more than 400 patients. Two of the wards were designated as foule [sic] wards for patients with venereal disease. The rest of the patients were designated as clean. Male and female patients were assigned separate wards. There were strict hospital rules to keep each of these groups separated from one another.

During most of the 18th century, patients were charged for their care. By the late part of the century, the charge was 3 shillings and 6 pence unless they had venereal disease, in which case the charge was 10 shillings and 6 pence. While it was possible to have the fees waived, most patients sought financial assistance from their parish or other sources.

For a medical student, the opportunity to study at a large hospital provided an opportunity to observe a wide variety of medical conditions. Since very few medicines at the time could prevent or cure conditions, it was possible to see the various stages as a disease progressed. The clinical insight was essential because diseases were diagnosed empirically based on symptoms.

At the conclusion of their studies, students had to pass an examination. Those who passed were given certificates issued by the surgeons who taught them. At one point there was a problem with the preprinted certificates that stated that students had diligently attended classes. That was not always the case. In 1737, it was decided that the word diligently should be omitted from the preprinted certificates and then, if appropriate, handwritten in. In the case of Galt, the top half of his certificate features the handwritten word, “diligently,” while the word is pre-printed on the bottom half.

By the early 19th century the teaching facilities were deemed inadequate. Land was purchased near the hospital and an operating theater for 400 people with seats was built. The dissecting room had several skylights and ventilators and could accommodate as many as 200 students. The same building also housed a museum that included specimens created by the hospital staff.

A number of years later the site was purchased to accommodate a railroad. In 1862, the hospital moved and, in 1868, found a home across the Thames River from Parliament where it now stands. Some sections of the old hospital and one of its churches can be seen today on St. Thomas Street. In the early 1820s the church attic was selected as the site to build an operating theater. The latter was boarded up in the mid-19th century and then rediscovered in 1956. It is currently a museum that displays a variety of surgical tools, artifacts, and art associated with the hospital. For more details, visit oldoperatingtheatre.com.

Robin Kipps is the Supervisor of the Pasteur & Galt Apothecary. One of her favorite activities is camping with her husband in their vintage travel trailer.

Resources

https:londonlives.org/static/StThomasHospital.jsp Accessed August 16, 2020.

E. M. McInnes. St Thomas’ Hospital. (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1963), p. 81.

George Motherby. A New Medical Dictionary, 2nd., (London: Printed for J. Johnson, G.G.J. and J. Robinson, and J.

Murray, 1785). [No page numbers were published. See image 603 on digitized copies on ECCO.]

https://londonlives.org/static/StThomasHospital.jsp. Accessed August 15, 2020.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.