The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg are home to a breathtaking range of folk and decorative art. Uncover the history behind beautiful objects in masterfully curated exhibitions in our series “Amazing Stories. Beautifully Told.”

Today we’re looking at A Map of South Carolina and a part of Georgia found in the Michael L. and Carolyn C. McNamara Gallery. This is part of The DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, home to remarkable objects that are useful as well as beautiful.

What is it?

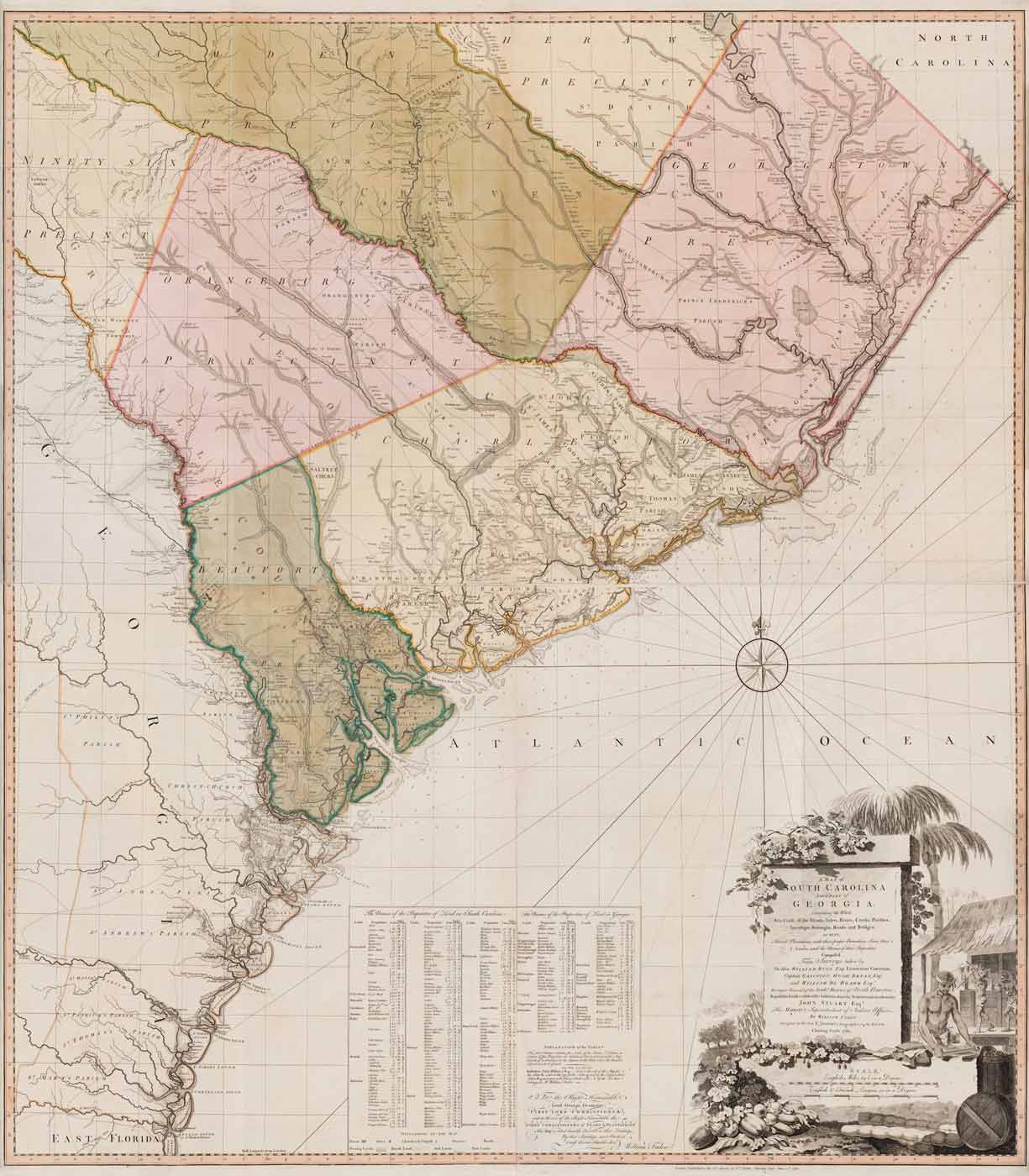

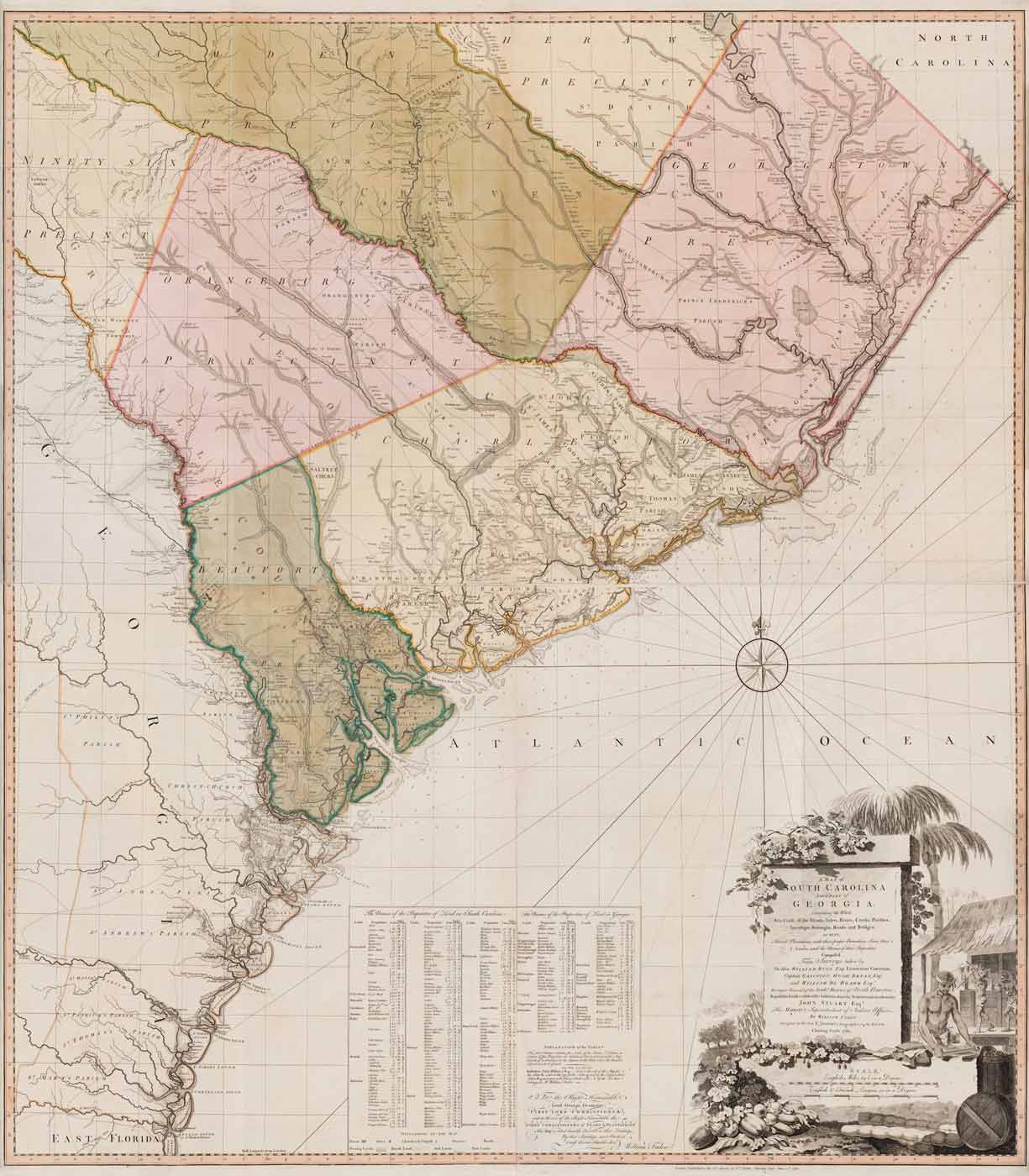

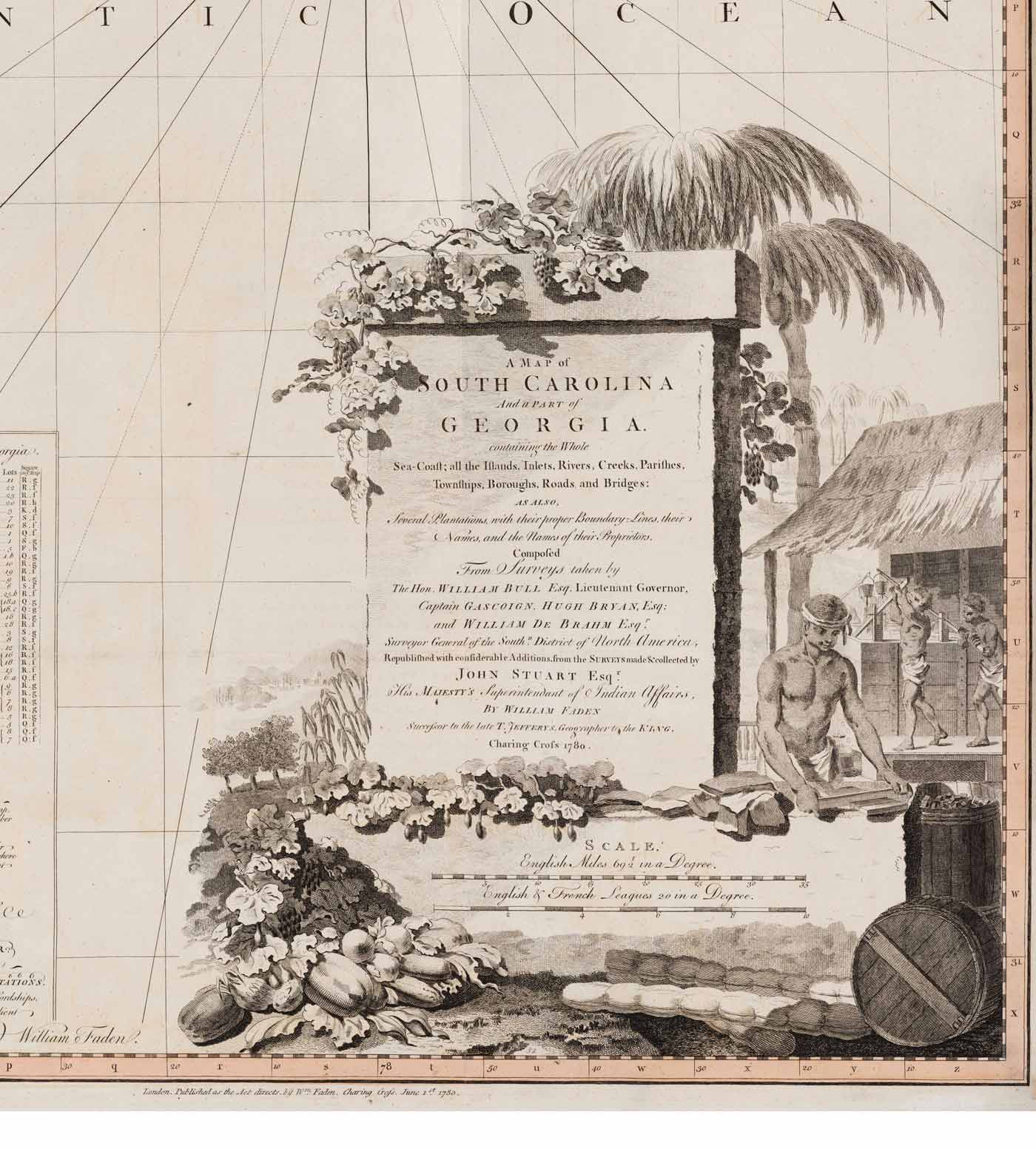

Hand-painted with watercolor and in almost pristine condition, this rare, engraved map was published at the height of the Revolution. Due to contemporary interest in the region, William Faden, successor to Thomas Jeffreys, updated the copper plates for a 1757 version made by cartographer William Gerard De Brahm. It was engraved on four sheets of laid paper, which when assembled, measure an impressive four feet square.

A MAP of SOUTH CAROLINA And a PART of GEORGIA. containing the Whole/ Sea-Coast; all the Islands, Inlets, Rivers, Creeks, Parishes,/ Townships, Boroughs, Roads, and Bridges: AS ALSO, Several Plantations, with their proper Boundary-Lines... (left) Cartographer William Gerard De Brahm (1718-ca. 1799), Published by Thomas Jeffreys (1710-1771), Great Britain, England, London, 1757, Black and white line engraving with period hand color on laid paper, Museum Purchase, 1973-322. The 1780 map (right)

What’s the story?

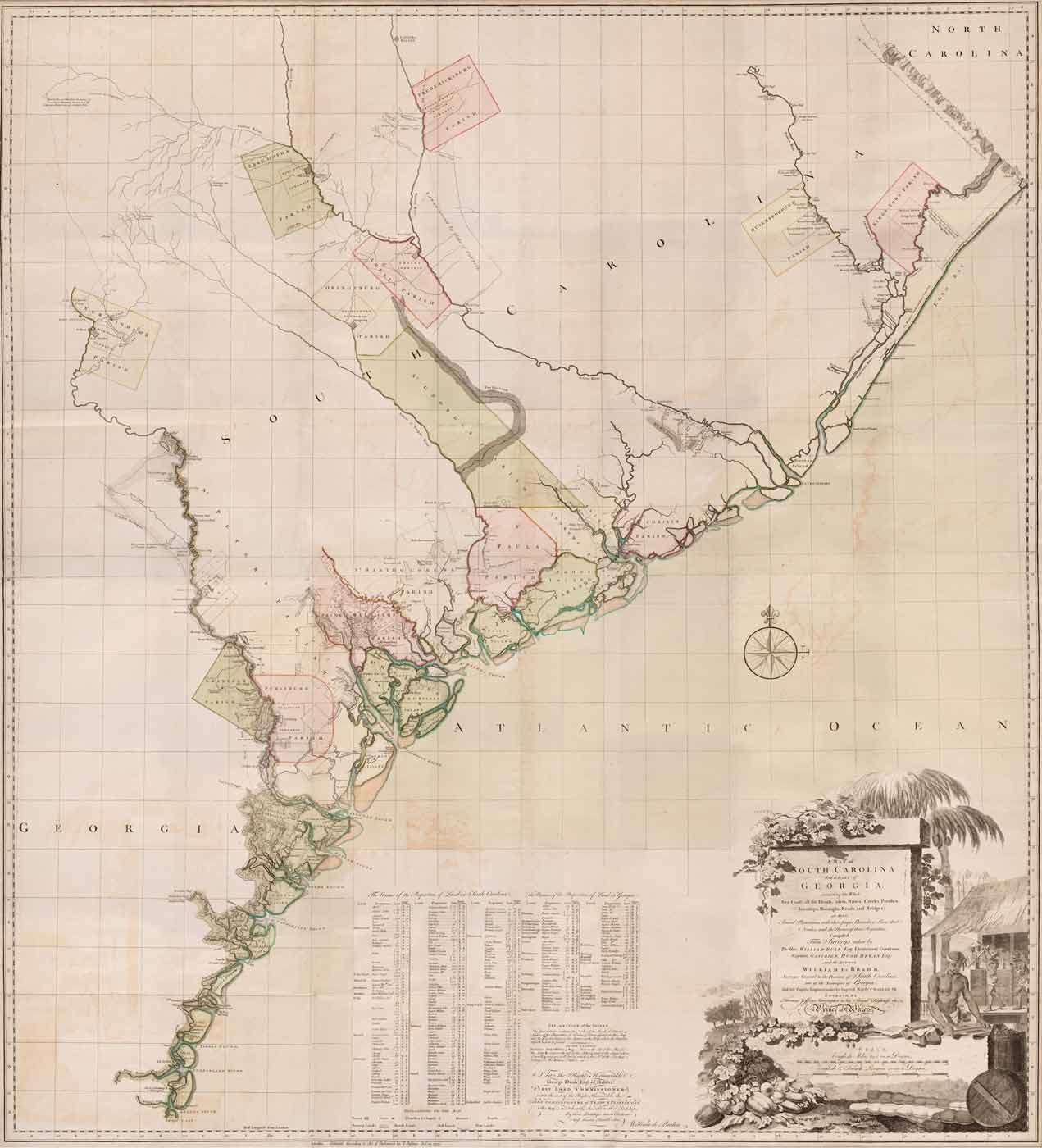

Today, when we want to know where we are or where we are going, we simply open an app on our phone or computer and expect to find the whole world accurately mapped-out for us. In the 18th century, mapmakers gathered old and new information in order to visualize the world on paper. This 1780 map of South Carolina and Georgia reveals how an older map was altered to reflect change over time, largely as the result of information gathered by an Imperial agent working on the edges of the British empire.

In 1757, De Brahm published a map of the region that was viewed then, as it is today, as a remarkable achievement of enlightenment map-making because rather than filling spaces where detailed information was lacking, it left them blank. They were an alluring call for financial interest in the colony and settlement. However, this land was not empty. American Indians inhabited it for millennia, and by 1757 it was also occupied by European traders operating outside of the formal trade networks that the Crown struggled to control.

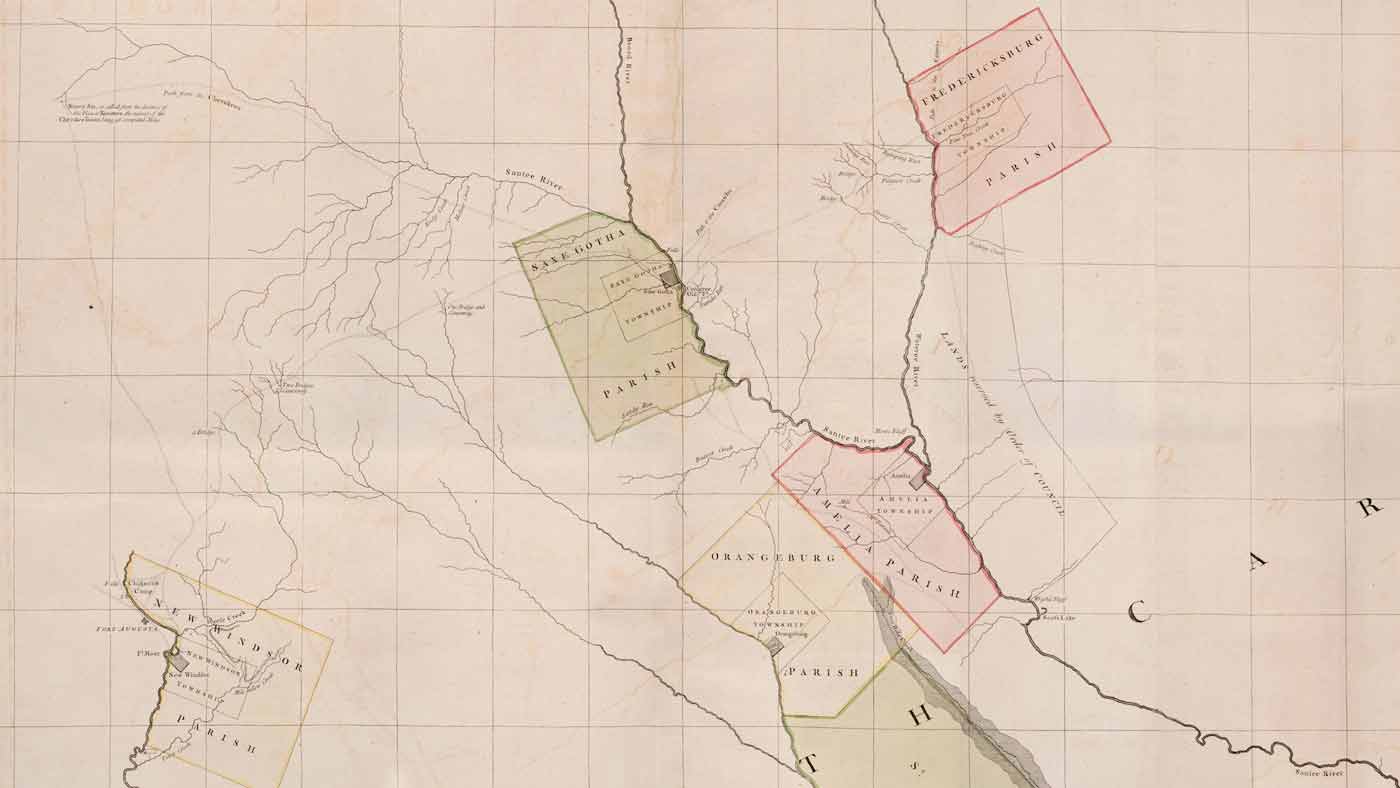

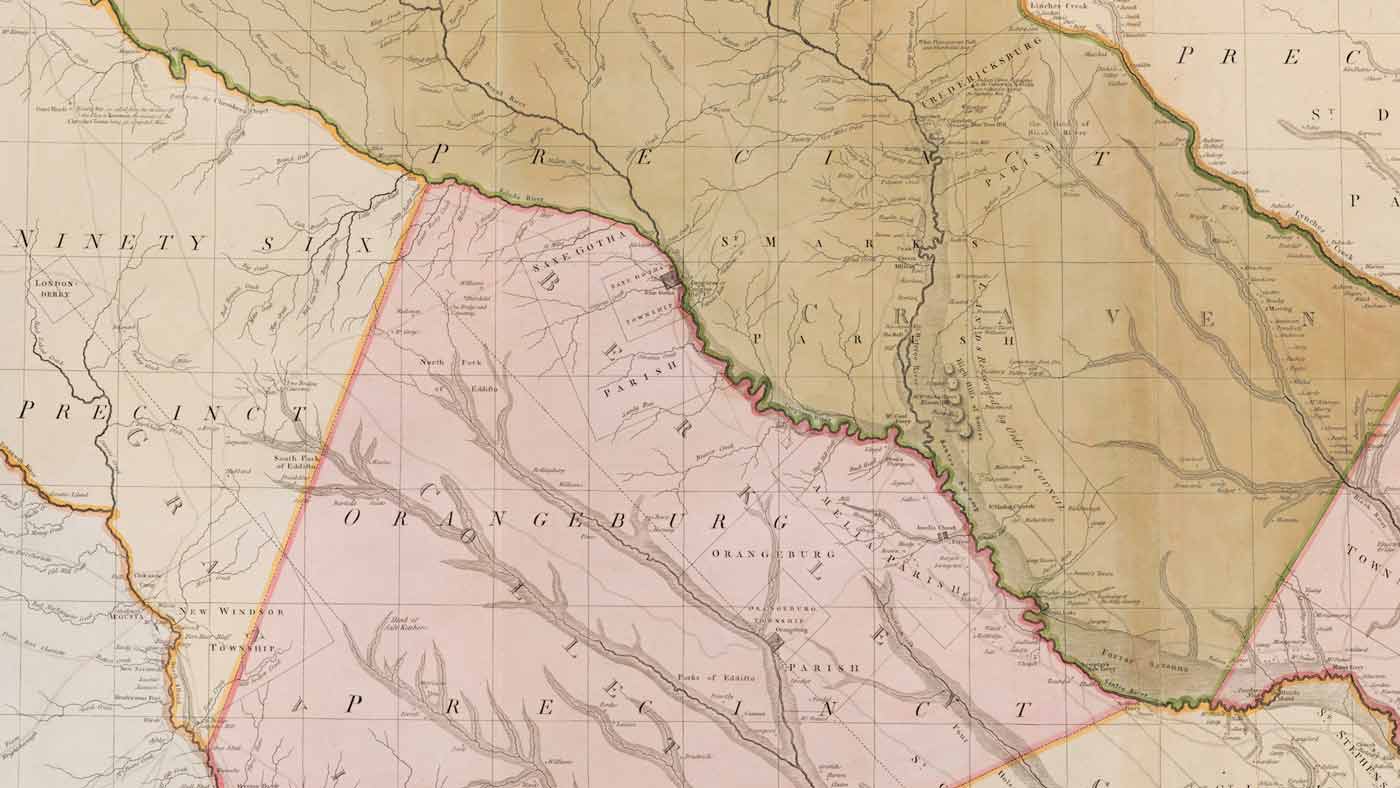

A comparison of the 1757 map (left) with the 1780 updated map in the area around present-day Columbia, South Carolina

Twenty-three years later, the map was updated at the height of the Revolution. Much of the new material was supplied by John Stuart, who served as Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern District. The Proclamation Line of 1763 created a barrier between the eastern land open to white settlers and the interior of the colony which was reserved for allied Indian nations. Stuart understood that maps were essential tools of empire. He bemoaned the lack of accurate maps needed to conduct his work, which often involved boundary disputes between Indians and settlers. Stuart and his staff gathered geographic information, sometimes gleaned from Native sources, and provided his findings to the Board of Trade. The board hired Jeffreys’s successor to reuse De Brahm’s copper plates in order to update the map as the Revolution reached the Southern colonies in 1780.

The revisions were so major that some scholars consider the result to be virtually a new map. This 1780 version included new county names, roadways, place names and settlements across the entire map, revealing the amount of information that was gathered over a span of less than 20 years. One element, however, remained the same: the cartouche depicting enslaved men processing indigo. The cartouche is a visible reminder that enslaved labor was the cornerstone that made this colony important and profitable.

Why it matters

We forget the time and effort that went into the creation of maps in the 18th century and who might have influenced or supplied the data used to create them. Stuart, who never lived to see the map completed, endeavored for over a decade to quantify an area that was ever-changing and never concrete. Analyzing his efforts to define imperial and Native space provides a better understanding of the complicated forces and tensions that undermined the British Board of Trade’s efforts to control and define the British empire was in North America.

See for yourself

You can find A Map of South Carolina and part of Georgia (2019-49, A&B) and tens of thousands of objects in online collection here. This map is also part of a new exhibition examining maps called “Promoting America: Maps of the Colonies and the New Republic.” We also invite you to see this remarkable object in person at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg and discover more amazing stories, beautifully told.

Katie McKinney, the Margaret Beck Pritchard Assistant Curator of Maps and Prints, has worked for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation for four years. She holds a master’s degree from the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture at the University of Delaware and a BA in art history and history from James Madison University. A native of Williamsburg, she fell in love with the Historic Area and history at the age of nine in Colonial Williamsburg's Junior Interpreter program.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital, plus, explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers to plan your visit.