My name is Adam Macbeth and I work as an archaeological field technician at Colonial Williamsburg, currently a member of the crew excavating at Custis Square. This spring, we each embarked on individual research projects aimed at taking a closer look into topics and artifacts that relate to recent excavations. For my project, I am taking a closer look into identifiable military buttons excavated not only at Custis Square, but throughout the town of Williamsburg.

Since its founding in 1699, Williamsburg has been involved in two wars fought on United States soil, the American Revolution and the American Civil War. In this project, I will use data recovered during archaeological excavations to better understand the specific military units that operated in Williamsburg during both wars.

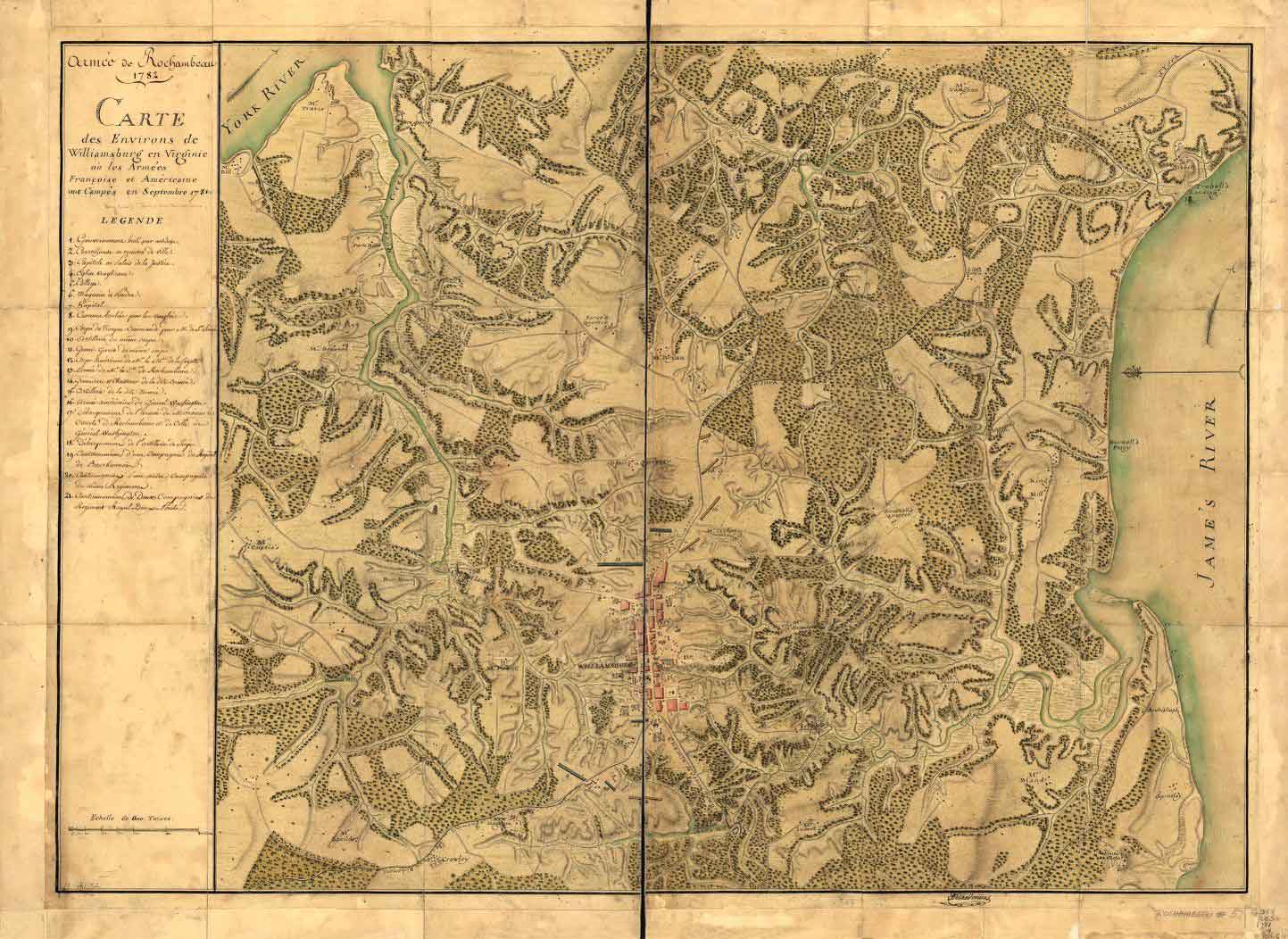

As I identify each button, along with the location where it was found, both pieces of information will be entered into a mapping program called GIS (Geographic Information Systems). Taken together, their mapped locations and button identities will allow us to analyze any possible spatial patterns that may emerge. This could help us to see where various military forces were stationed and may even show where individual identifiable units were encamped or fighting in Williamsburg. While we have several maps from the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, which, similar to the Désandrouins map (Figure 1), show where military action took place in and around Williamsburg, they are rarely specific about where individual units were stationed. By mapping each button according to where it was recovered archaeologically, I hope to supplement the information included in these historic maps.

To begin this project, I will test the method described above on a small scale by focusing my analysis on the identifiable military buttons found during the current excavation at Custis Square, along with buttons from Colonial Williamsburg’s artifact study collection. This will allow me to gain a preliminary understanding of the success of my methodology. If my test produces promising results, the same techniques will be applied on a larger scale.

If successful, the results of my analysis could be used to share archaeological data in creative new ways. For example, my results could be used to illustrate military movements within web-based, interactive “tours” called a Story Maps. A Story Map could identify individual military units, where they are from, where they fought, how they traveled, and finally, how they ended up in Williamsburg. Another possible product could be thematic maps that use the data from my project to enhance existing historical maps.

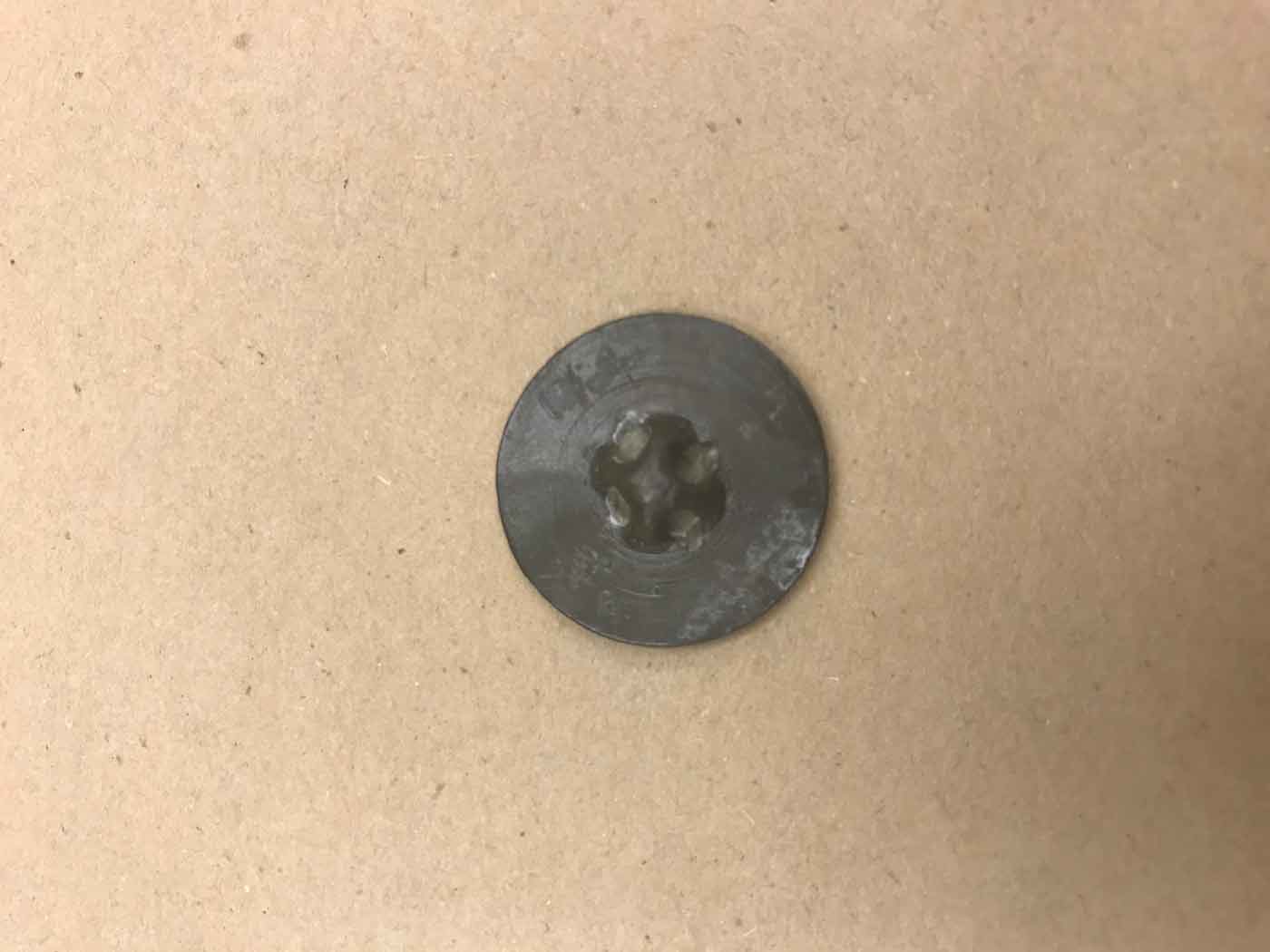

So far at Custis Square, several military units have been associated with the property through the recovery of buttons. One of these buttons (Figure 2) was identified by the front marking of “64” in the center with two concentric circles and a raised stipple above the center, along with a reverse side featuring a turret-style fastener (Figure 3). This button belonged to a soldier in a French unit, quartered in the town of Williamsburg in 1781. The unit was composed of soldiers

from several towns around France and was first formed in 1765 under unit number, 47. In 1776, the battalion’s number designation was changed to 64, the number it would use until the end of the war. Buttons recovered at Yorktown battlefield show that some members of French military units were still wearing old unit numbers on their uniforms even after new numbers were designated. The 64th French regiment known as “Royal de l’Artillerie,” widely regarded as the most technologically advanced artillery unit at the time, was first stationed in Williamsburg and would eventually participate in the Battle of Yorktown in 1781.

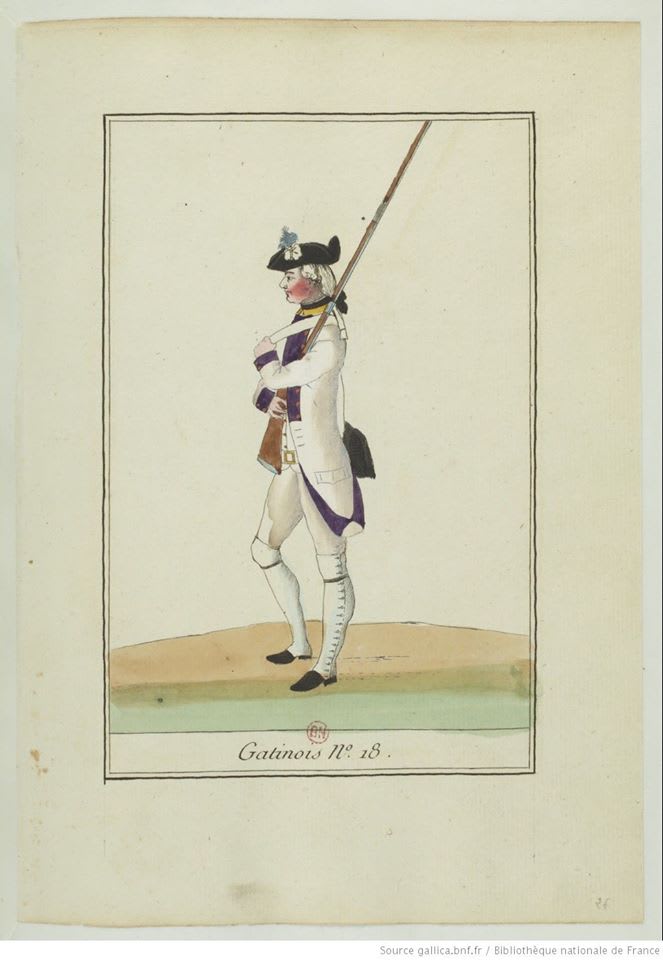

Another button recovered at Custis Square belonged to a member of the French 18th Infantry Regiment of the line known as “Regiment de Gatinois” (Figures 4, 5). The button has a front marking of “18” surrounded by a broken circle with a raised stipple in the center. This regiment saw action in several locations during the Revolutionary War including at the sieges of Savannah in 1779, Pensacola in 1781, Yorktown in 1781.

In addition to buttons associated with the American Revolution, several buttons from the Civil War have been excavated at Custis Square (Figure 6). These buttons include a Confederate Infantry officer’s button, identified by the front marking of the letter “I”. Another Confederate button that belonged to a Virginia Regiment was recovered during excavations and is identified by the front marking of the Virginia State seal with the words “Sic Semper Tyrannis” surrounding it. A Confederate Navy button, identified with a front marking of “C S N” underneath an anchor, was also recently recovered. While these buttons can help us identify different branches of the Confederate forces present at Williamsburg, at this time they have not been attributed to any specific unit. The same is true for the general service eagle buttons recovered at Custis Square which are associated with Federal units of the same period or before.

All the buttons recovered at Custis Square are being processed through our conservation facilities here at Colonial Williamsburg. While that process is being completed, we have begun to tie each button to the location on the map where it was excavated. As a bonus, the conservation process itself often reveals even more information about an item’s materials and how it was made, opening up new lines of inquiry for future research. With new answers always leading to new questions, I look forward to uncovering more buttons, continuing to learn more about each one that we recover, and seeing how each button we find adds to our understanding of military movements in 18th- and 19-century Williamsburg.

Adam Macbeth is an archaeology Field Technician at CWF. He earned his Bachelor’s in Archaeology from Millersville University and has previously worked as a field technician for Thomas Jefferson's Poplar Forest and AECOM.