Was the United States Founded as a Republic or a Democracy?

It was an impossible task. When the delegates to the Constitutional Convention assembled in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, they saw political perils everywhere. A nation stretched across a continent risked disintegration. A democratic government, they feared, might dissolve into anarchy. A republican system, conversely, invited an aristocracy to rise. If anyone asks you to design a government, run away.

The United States was neither founded as a pure republic nor as a pure democracy. Rather, the Framers of the Constitution believed that a mixed government, containing both republican and democratic features, would be the most resilient system. While they agreed on this, they did not agree on just how democratic the nation should be. This was deeply controversial during the revolutionary era. It remains so today.1

What was a “Democracy” in the Eighteenth Century?

Athens. Athenian democracy was the primary historical example of democracy referred to by the Founders. Anonymous, after a painting by Philipp Foltz, Pericles’s Funeral Oration (ca. 1875-1880). Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum.

According to James Madison, democracy was a form of government where “the people meet and exercise the government in person” and decide issues by voting.2 The Framers were not impressed by this system. Alexander Hamilton said that “ancient democracies” lacked “one feature of good government. Their very character was tyranny.”3 John Adams called direct democracies “impracticable.”4 James Madison saw direct democracies as “spectacles of turbulence and contention.”5

Why the distrust for democracy? In the eighteenth century, it was not clear how direct democracy would function across vast geographic areas and with large populations. Political thinkers had long concluded that direct democracies could only work in relatively small city-states. The colonies’ elite leaders also worried that democracies tended to dissolve into factional infighting and allow a majority to overpower minority views.6

What was a “Republic” in the Eighteenth Century?

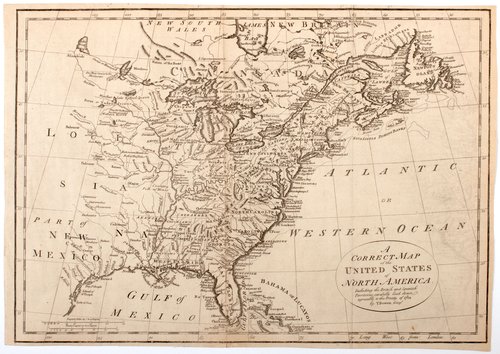

Madison believed that an “extended” republic could function across a nation as large as the United States. New royal and authentic system of universal geography (London, 1790). Courtesy of American Revolutionary Geographies Online.

In a republic, according to Madison, the people “assemble and administer” government by empowering “their representatives and agents” to make decisions.7 James Madison argued that “a republic may be extended over a large region,” because it only required representatives to travel, rather than all voting citizens.8 In a well-designed republic, representatives would focus on the broader public good, rather than local or factional interests.9

Yet some critics feared that republics gave too much power to a small, usually wealthy, group of citizens. They easily imagined a republic giving way to “an aristocracy.”10 One opponent of the U.S. Constitution, for example, suggested that the proposed government would allow “opulent and ambitious” men to subvert “the equality established by our democratic forms of government” in state constitutions.11

“An Excess of Democracy” in the Early Republic

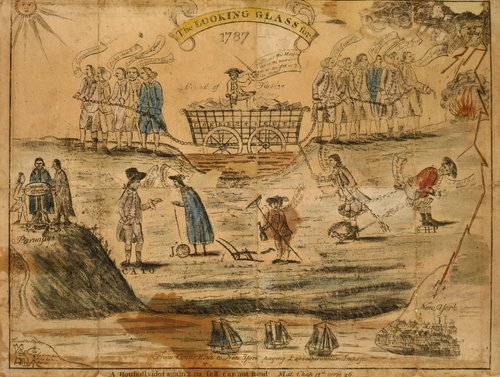

This political cartoon from the debate over the Constitution depicts the state of Connecticut as a wagon stuck in the mud under the weight of paper money. It is being pulled in opposite directions by the state’s factions. Amos Doolitte, “The Looking Glass for 1787” (New Haven: 1787). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In 1776, the Declaration of Independence proclaimed that all men were created equal. In the following years, Americans embraced this idea. They experimented with democratic systems in their state constitutions.12 But by the late 1780s, the luster of democracy had dulled. U.S. political leaders blamed the nation’s growing instability on the democratic elements of state governments. For example, they claimed that the legislatures’ populist economic policies, such as issuing paper money, had caused an economic depression.13 Protests and rebellions prevailed. The nation’s future seemed to be in peril, and democracy was the culprit.14

Madison warned that “a factious spirit has tainted our public administrations.”15 During the Constitutional Convention, Massachusetts delegate Elbridge Gerry declared that “the evils we experience flow from the excess of democracy.”16 Democracy had shifted from something to strive for to something that needed to be checked in American government. At the Convention, the Framers saw democracy as an element that they could blend into a republican form of government. It was just a matter of how much democracy to include.

A Democratic Republic

The Constitution’s Framers ultimately created what Americans today would call a democratic republic, or a representative democracy, where people vote for representatives to govern on their behalf. But their distrust of democracy showed through in the final document, which contained relatively few democratic elements.

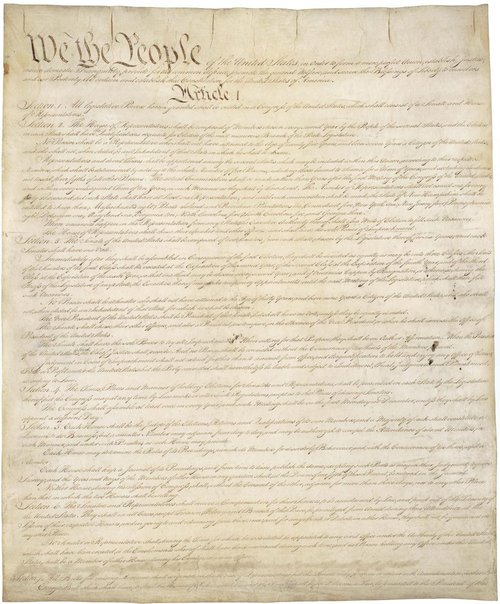

The Constitution of the United States. Courtesy of the United States National Archives.

The president, senate, and judiciary would be chosen by representatives, rather than the people. Only the House of Representatives would be directly elected.17 But some opponents of the Constitution complained that even this branch “will have but very little democracy in it.”18 Representatives would serve relatively large constituencies, initially around 30,000 people each. As Madison explained, larger districts would ensure that “members of limited information” would not be elected. But critics worried that having tens of thousands of constituents would keep representatives from close contact with ordinary people.19 Moreover, since the Constitution allowed state legislatures to decide who was qualified to vote, the only people choosing representatives were property-owning adult white men.

In the 1790s, the French Revolution re-animated the ideal of democracy, leading more ordinary people to assert that they should have a role in their government. By 1800, it had shifted once again to refer mostly to Thomas Jefferson’s political party, which advocated for a moderate version of popular rule.20 In the early nineteenth century, the definitions of republic and democracy merged as democracy came to refer to the peoples’ practice of popular sovereignty through the election of representatives.21 While the Constitution incorporated some elements of democracy, “We the People” have, since its inception, defined and redefined what it means to live in a democratic republic.

“We the People”

While the original Constitution’s democratic elements were limited, perhaps its most radical feature was its ability to be amended. In the two centuries following the Constitution’s ratification, Americans have incorporated more democratic elements into their government. In 1913, the 17th Amendment gave voters, rather than state legislatures, the power to choose their state’s senators. Who can participate in representative government has expanded as well: the 15th Amendment guaranteed African American men the right to vote, the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote, and the 26th Amendment lowered the voting age from 21 to 18.22

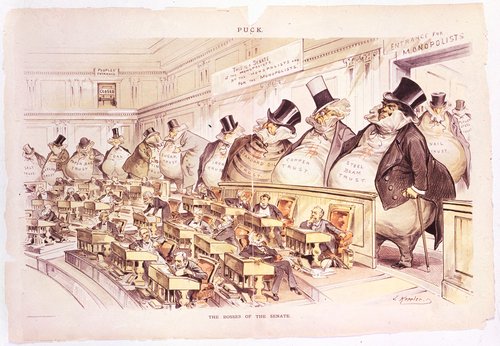

This political cartoon called attention to the perceived influence of corporate influence in the Senate in the late nineteenth century. “The Bosses of the Senate” (1889). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

While the Constitution’s Framers limited the democratic elements incorporated in the Constitution, they still created a government by “We the People.” Over time, “We the People” have expanded democracy’s role in government, dedicating ourselves to the idea that having our voices heard is an essential part of government. Today, democracy in the United States signifies more than just a system of government. It represents a set of ideals and values the nation aspires to.

Watch the Video

What kind of government did the Founders create for the United States? And did they have the same definition of a democracy as we do today? Discover why our government is set up the way it is, how your voice shapes our government and why voting matters today.

Sources

Cover image: Howard Chandler Christy, Signing of the Constitution (1940). Courtesy of the Architect of the Capitol.

- Seth Cotlar, “Languages of Democracy in America from the Revolution to the Election of 1800,” in Mark Philp and Joanna Innes, eds., Re-Imagining Democracy in the Age of Revolutions: America, France, Britain, Ireland 1750-1850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 18.

- James Madison, “The Federalist Papers: No. 14,” The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed14.asp.

- “New York Ratifying Convention. First Speech of June 21 (Francis Childs’s Version), [21 June 1788],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-05-02-0012-0011.

- “From John Adams to the President of Congress, 25 October 1781,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-12-02-0028.

- James Madison, “The Federalist Papers: No. 10,” The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed10.asp.

- Madison, “Federalist Papers: No. 10.” James Madison or Alexander Hamilton, “The Federalist Papers: No. 51,” The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed51.asp.

- James Madison, “The Federalist Papers: No. 14,” https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed14.asp.

- Madison, “The Federalist Papers: No. 14.”

- Madison, “Federalist Papers: No. 10.”

- “Cincinnatus,” New-York Journal, Nov. 29, 1787, p. 2.

- “A Republican,” New-York Journal, Sept. 6, 1787, p. 2.

- Terry Bouton, Taming Democracy: The People, the Founders, and the Troubled Ending of the American Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 6-7; Cotlar, “Languages of Democracy in America,” 16-17.

- Woody Holton, “Did Democracy Cause the Recession That Led to the Constitution?” Journal of American History 92 (Sept. 2005): 442–69.

- Bouton, Taming Democracy, 146, 166-167; Woody Holton, Unruly Americans and the Origins of the Constitution (New York: Hill and Wang, 2007).

- James Madison, “The Federalist Papers: No. 10.”

- “Madison Debates, May 31,” The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/debates_531.asp.

- “The United States Constitution: A Transcription,” National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript.

- Observations Leading to a Fair Examination of a System of Government Proposed by the Late Convention; And to Several Essential and Necessary Alterations In It. In A Number of Letters from the Federal Farmer to the Republican (New York: Greenleaf, 1787), 16. This pamphlet is sometimes attributed to Richard Henry Lee.

- “The Federalist Papers: No. 58,” The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed58.asp. Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), 222.

- Cotlar, “Languages of Democracy in America,” 14, 24.

- Katlyn Marie Carter, Democracy in Darkness: Secrecy and Transparency in the Age of Revolutions (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023), 4.

- “Voting rights laws and constitutional amendments,” usa.gov, https://www.usa.gov/voting-rights.