History is not a simple story. Each event brings different actors to the stage who possess complex dualities and kaleidoscopic tapestry in which they may be viewed and understood. Our own founders demonstrate this truth to us. Bearing this in mind, I would like to draw attention to a dynamic and important character in the story of our founding. Most are familiar with him from the television program Turn, which filmed partially here in Williamsburg. Yet, John Graves Simcoe is more complex and drastically different from the evil, scheming character on the program.

At this point, you may ask what John Graves Simcoe has to do with Colonial Williamsburg? Well, much like the show, the real John Graves Simcoe walked the streets of Williamsburg in 1781. To better understand the role John Graves Simcoe played in America’s war for Independence and the larger spectrum Great Britain played in North America, here are five things you should know:

Simcoe served as Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada (the area which is now Ontario and the area along the Great Lakes) from 1791 to 1796.

During that time, he established the city of York, now Toronto. In 1793, he severely restricted the slave trade by signing into law the Anti-slavery Act which freed enslaved people older than 25 and encouraged enslaved people to move into Upper Canada. These actions led to total abolition of slavery within the boundaries of Upper Canada by 1810 — 24 years prior to the British Empire and 72 years before abolition in the United States. As the first leader of this largely wilderness colony, Simcoe sought to expand the population through immigration and create a superior and refined form of government. To this day, the first Monday of August is celebrated in Toronto as Simcoe Day, celebrating a man who is viewed as a Canadian amalgamation of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, both founder and emancipator.

Simcoe was a captain in the British 35th Regiment of Foot in 1775 and was placed in command of the Queen’s Rangers in October 1777, gaining further promotion to lieutenant colonel in 1778.

Shortly after the December 1775 Battle of Great Bridge, the Queen’s Own Loyal Virginia Regiment was absorbed into the larger body of the Queen’s Rangers. To give a bit of background on this body, they were American Loyalists also known as the 1stProvisional American Regiment with roots tracing back to the French and Indian War. They would see action in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, Virginia, and elsewhere. The Rangers ultimately fell under the chain of command of General Benedict Arnold.

Simcoe’s record with the Rangers is one of perseverance and discipline. While not focusing particularly on formal drilling, he insisted on other facets important to battle, including physical fitness, rapid movement, bayonet fighting, and most importantly, field discipline. Simcoe thought there was little appreciation of light infantry and he sought to reform his opinion for both the American campaign and wider use in the British military operation. His actions, training, and valor, not only led to the respect of those serving under him, but also to great personal successes in the military at large. Americans eventually came to view Major Simcoe the same way. They may not have liked him because he was disciplined and successful in the field, but they also recognized him as a professional soldier and officer fulfilling his duty in wartime.

John Graves Simcoe was in Williamsburg, or at least very near it.

In the buildup to the Siege of Yorktown, he was following General Cornwallis and looking out for Lafayette and General “Mad” Anthony Wayne. He was also interested in what efforts would be required to control the roads leading to Yorktown, including Williamsburg. This concern, in part, led to the Battle of Spencer’s Ordinary. This battle highlights the capacity of Simcoe’s leadership and brilliance as a tactician. While not as famous as battles like Saratoga or the Siege of Yorktown, the 1781 Battle of Spencer’s Ordinary set up the ending stages of the American War for Independence. Having been shadowed by Lafayette’s forces and evading one another for nearly a month, they finally engaged when Simcoe’s forces were moving down the main road toward Williamsburg. Having broken off from Cornwallis, Simcoe had less support than did the combined American and French forces. Yet, Simcoe’s skill as a military strategist served him well.

Despite the disparity in troop counts and positions, Simcoe was able to seize the field briefly and win the day, though it may not look that way given the Siege of Yorktown that followed. Simcoe arranged his forces at Spencer’s Ordinary to appear larger. He then led several calvary charges that forced the rebel armies from the field. The tact and strategy which Simcoe provided at Spencer’s Ordinary reflects the broader statement that Simcoe was a military strategist and officer. However, he was severely wounded in the battle. In part because of wounds and an illness, Simcoe was sent back to England prior to the Siege of Yorktown.

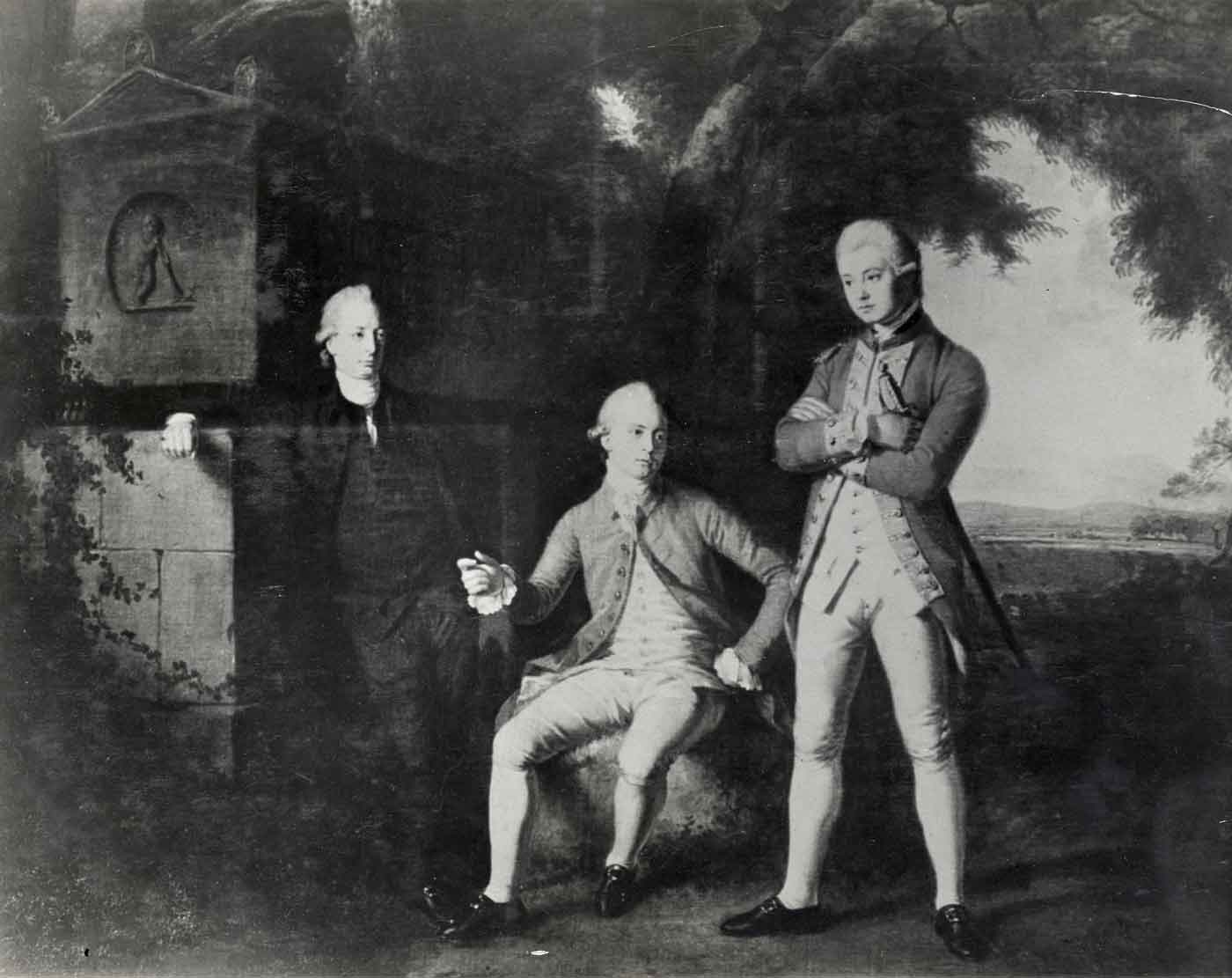

Simcoe was the well-educated son of John and Katherine Simcoe.

His father, John Graves, was a member of the Royal Navy who had attended the Exeter Grammar School and Eton College. When one looks at Simcoe’s story broadly, it is notable how his story parallels that of other famous people of the era.

Simply put, John Graves Simcoe was not a blood-thirsty and evil cartoonish villain, but rather a well-educated and disciplined military officer.

His part in the story of the American War of Independence is understated and demonstrates that history is not simply a story of good and bad, but one comprised of complex and interwoven narratives. The collective story of John Graves Simcoe is a familiar one in the American part of the story. A professional military officer whose bold strategy and discipline led to successes in the field and then parlayed the military career into a political office which, in turn, impacted millions of lives.

While the above provides only a brief snapshot of John Graves Simcoe’s career, his legacy, and that of thousands of others are part of the rich and complete story of the past we tell at Colonial Williamsburg. A broader understanding of the 18th century demands that we share the diverse stories of the entire community. History is complex and does not exist to make us feel comfortable, but to learn from it so that we can be better.

John Graves Simcoe is just one of many stories in 1700s Williamsburg. If you would like to learn more about John Graves Simcoe, I suggest reading some of the following works!

Christopher Glick has worked with Colonial Williamsburg since 2019 and now resides in Richmond. He loves to read, play board games, and ride roller coasters in his spare time.

FURTHER READING

John Graves Simcoe, 1752-1806: A Biography by Mary Beacock Fryer and Christopher Dracott. 1998.

A Journal of the Operations of the Queen's Rangers from the End of the Year 1777, to the Conclusion of the Late American War by John Graves Simcoe

The Queen’s Rangers by Donald J. Gara. 2015.

George Washington’s Secret Six by Brian Kilmeade. 2013.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.