The Fairfax Resolves

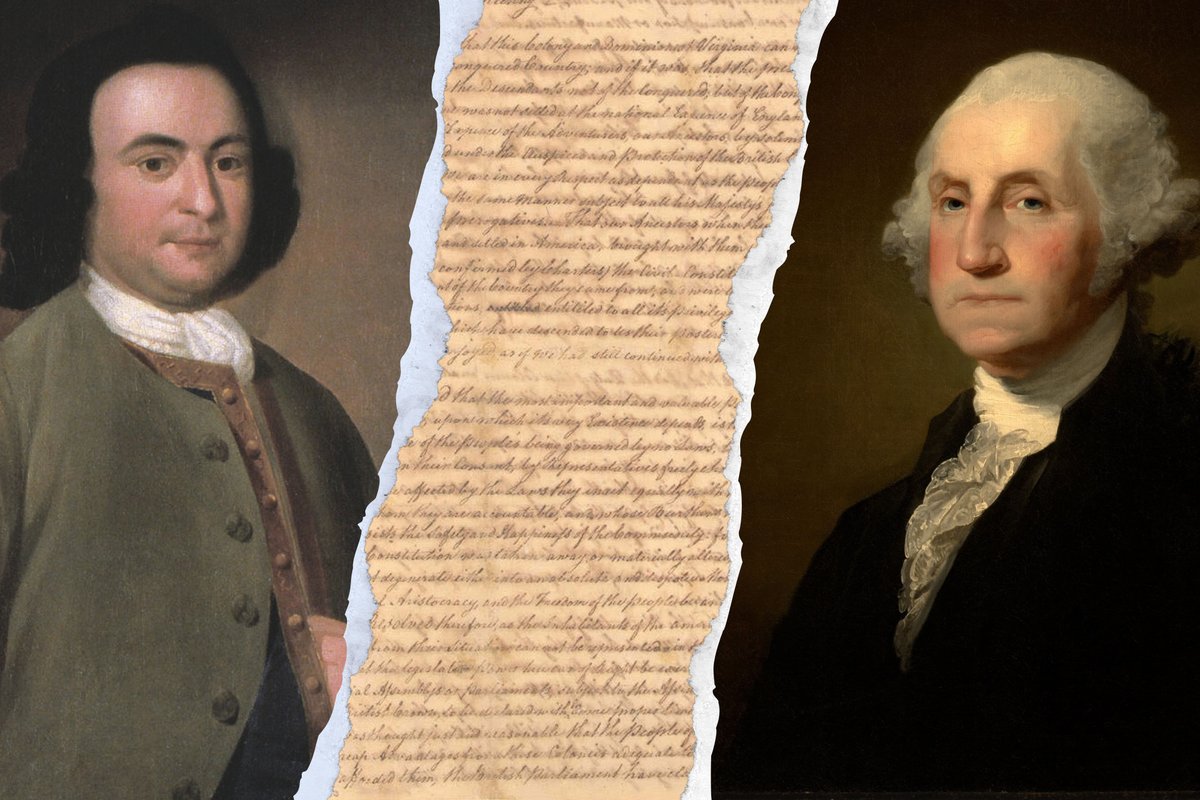

Angry Virginian tempers were rising like summer mercury in July 1774. It was an “exceeding Warm” morning, according to George Washington, when the people of Fairfax County approved a series of radical resolutions. Likely co-authored by George Mason and Washington, these resolutions are now known as the Fairfax Resolves. Though seldom discussed today, they created an influential model that helped to lead Virginians and eventually all the American colonies toward independence.

Background

The Tea Crisis had hit Virginia. It began in 1773 when the British government attempted to rescue the failing British East India Company by creating a monopoly for the company on tea within the British empire. After Bostonians protested this legislation by dumping a shipment of East India Company tea in the harbor, news arrived that Parliament planned to punish Boston by closing its port.

Virginia’s House of Burgesses, the elected half of the colony’s legislature, protested these plans. In response, the royal governor John Murray earl of Dunmore dissolved that assembly. The ex-Burgesses then called for a new convention in Williamsburg’s Raleigh Tavern at the beginning of August. This gathering would not be recognized or governed by the British government. County elections for this new body were set for June and July. Virginians asked themselves: What should we do next? It was a busy time, heady with revolution.

Rain Delay

Even in the face of tyranny, the harvest came first. A meeting had been planned in Fairfax County for July 5 to choose local delegates for the Williamsburg convention. Yet as Fairfax County resident George Washington explained, “heavy & powerful Rains” the night before had led the election to be called off. Being harvest season, Washington wrote “the Wheat as well as Plants requird all the care and attention that could be bestowd on them.” Those who had gathered decided to appoint a committee to “frame such Resolves as we thought the Circumstances of the Country would permit us to go into,” and go home.

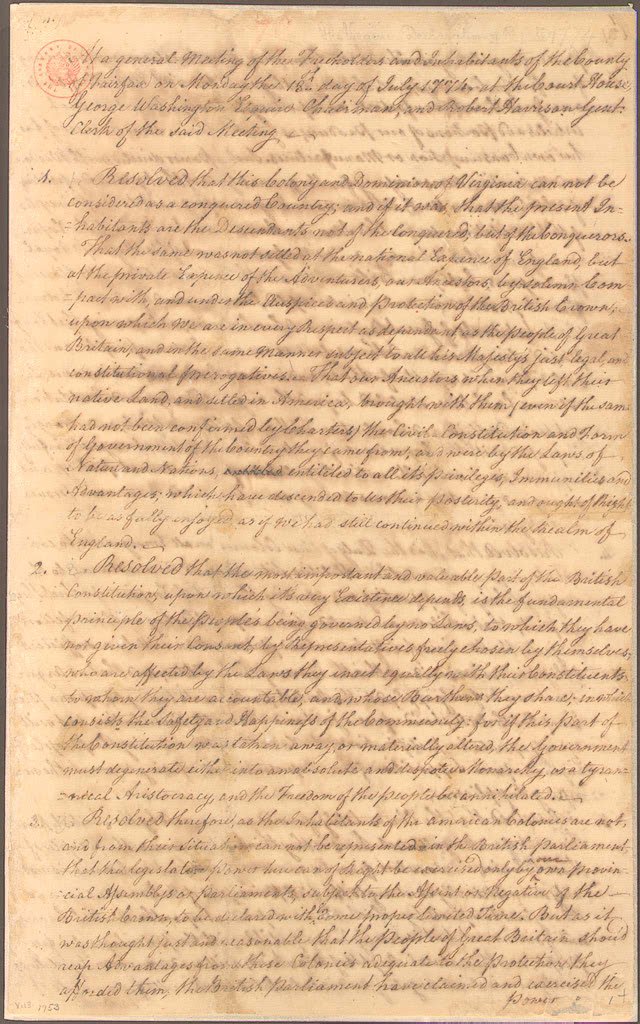

George Mason’s manuscript copy of the Fairfax Resolves. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

For the next two weeks, the committee wrote the document that became known as the Fairfax Resolves. The composition of this committee and the precise authorship of the resolves remains unclear. Many historians believe that George Mason was the principal author. Parts are written in his style and the only surviving copy is in Mason’s handwriting.1 Some evidence also suggests that the resolutions were drafted by a committee that included Mason, Washington, and others.2 Regardless of who wrote them, though, the voters of Fairfax County approved these resolutions at a meeting in the local courthouse on July 18, 1774.

Principles

The Fairfax Resolves were a collection of twenty-four resolutions. They began with two main ideas. The first resolution stated that the earliest British colonists who settled in North America had carried with them the constitutional rights of British subjects. The second resolution noted “that the most important and valuable” feature of Britain’s constitution was “the fundamental Principle” that no one could be governed by laws to which they had “not given their Consent, by Representatives freely chosen by themselves.”3

The fifth resolution concluded that Parliament’s recent actions (later known as the “Intolerable Acts”) were “incompatible with the Privileges of a free People,” and would lead the colonists to suffer in “Slavery and Misery.”4 The Fairfax Resolves represented an escalation of Virginia’s protests because they rejected Parliament’s authority to legislate for the colonies.5 A veiled threat also lurked near their end. If the King pushed the colonists “to a State of Desperation,” resolve twenty-three reminded him that “from our Sovereign there can be but one Appeal.”6 With grievances unanswered, desperate colonists might turn to violence.

A Path Forward

The Fairfax Resolves were, first and foremost, a response to the Tea Crisis unfolding in the British empire. They called for Virginians to collect funds to help Boston’s poor, who would suffer from the closure of the city’s harbor. They also suggested that Virginians should refuse any further dealings with the British East India Company and should burn the tea they owned. But in a gesture that reflected an elite planter class’s respect for private property, they also offered to help repay the East India Company for the tea dumped into Boston harbor.7

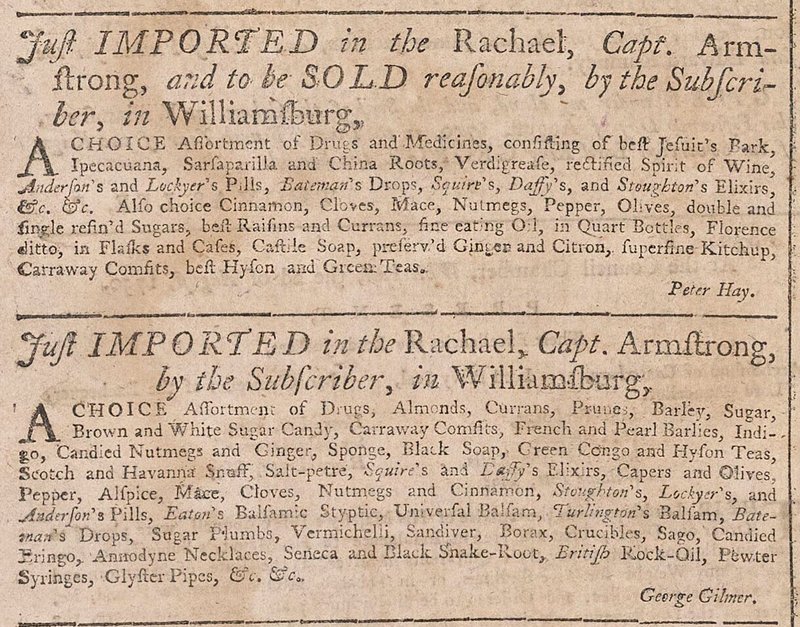

Advertisements from the Virginia Gazette demonstrate colonial Virginia’s dependence on imported goods. Virginia Gazette (Hunter), Jan. 17, 1750, p. 4. Click the image to see it in context.

The Fairfax Resolves echoed other colonists’ calls for an intercolonial congress to make a “Plan for the Defence and Preservation of our common Rights.” But they didn’t wait for this congress to assemble. Nine of the twenty-four resolutions detailed a plan for new economic sanctions on Britain. Those who signed onto these resolutions agreed to consume less, produce more, and import only necessary items from Britain. But if their protests were not addressed by the next year, the Fairfax Resolves suggested “that all Exports of Produce” from the colonies to Britain “shou’d cease.” After the current crop of tobacco, they would “not plant or cultivate” more. These policies were popular among Virginia elites because of plummeting tobacco prices and rising debts.8

This was not Virginia’s first boycott. Five years earlier, the “Virginia Association,” also authored by Mason, had tried to pressure Parliament to soften its colonial policies. But merchants widely ignored this agreement. Perhaps as a result, the Fairfax Resolves included clear enforcement rules. Local committees would require merchants to take an oath to uphold the agreement. They would provide a certificate to those who took the oath and would advertise the names of those who refused. Signatories would shun anyone who rebuffed the boycott.9 The strictness of these rules reflects the revolutionaries’ ambitions. If they could wield the colonies’ full economic power, they hoped Parliament might relent.

The Slave Trade

The Fairfax Resolves’ seventeenth resolution stated, “no Slaves ought to be imported into” the colonies during their “present Difficulties and Distress.” It further declared that the signatories hoped to see “an entire Stop for ever put to such a wicked cruel and unnatural Trade.”10 While Mason, Washington, and other Fairfax County elites were all enslavers, they were also coming to view the slave trade as a threat to Virginia’s social order. In 1765, Mason had complained to Washington about “the Introduction of great Numbers of Slaves” into Virginia. Elite Virginians feared that a growing enslaved population would spark widespread slave revolts. They also hoped that ending the slave trade would reduce debt, raise the value of enslaved people already in Virginia, and end the oversupply of tobacco that was driving down prices.11

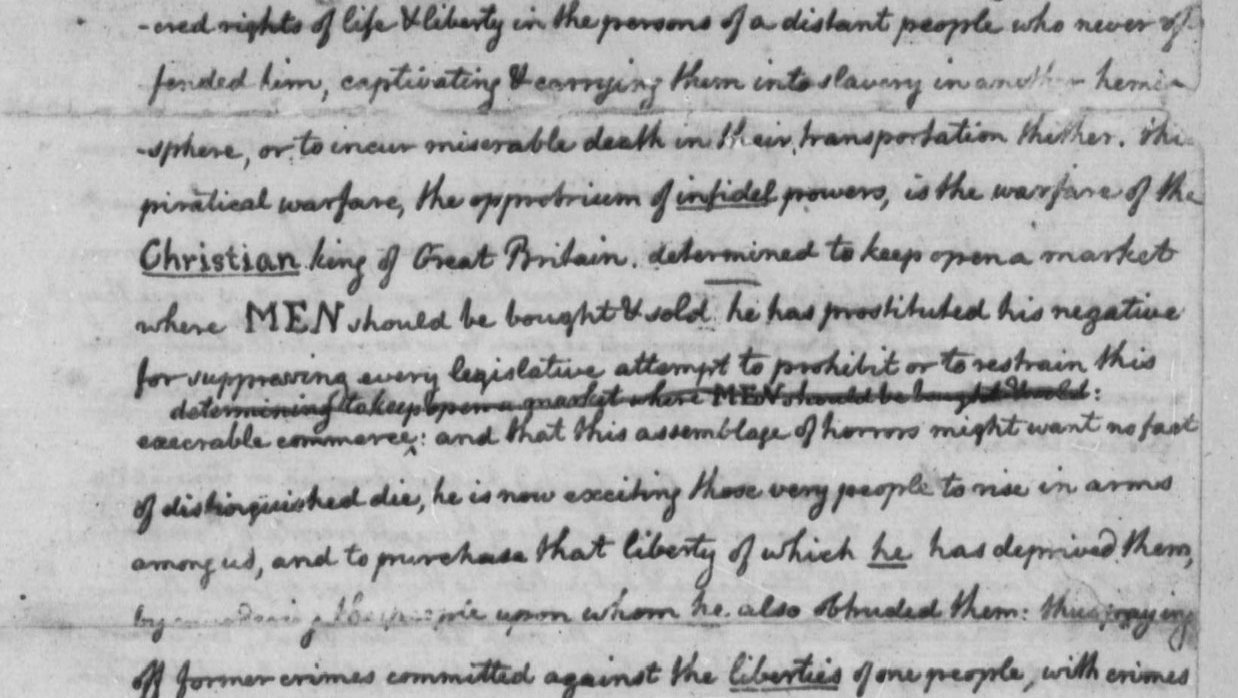

Rough Draft of the Declaration of Independence

Thomas Jefferson’s original draft of the Declaration of Independence, composed two years after the Fairfax Resolves, contained a lengthy paragraph listing George II’s protection of the slave trade as a grievance leading to independence. This was removed from the final version of the Declaration. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Manuscripts Division.

In attempting to end the importation of enslaved people, elite Virginians could seek the moral high ground while also serving their own interests. Virginia’s colonial government repeatedly tried to reduce the number of enslaved people being trafficked into the colony. But the British government rejected these actions. In 1772, the House of Burgesses complained to King George III that the slave trade, “a trade of great Inhumanity,” was endangering “the very Existence of your Majesty’s American Dominions.”12 Drawing on these sentiments, the Fairfax Resolves’ boycott of imported Africans aimed both to punish Britain and protect white Virginians.

Impact

Dozens of Virginia counties passed resolutions during the Tea Crisis. But the Fairfax Resolves were the most detailed, radical, and influential of them. One of the earliest colonial texts to reject Parliament’s authority over the colonies, they are often considered to be a landmark text in Virginia’s road to revolution.13

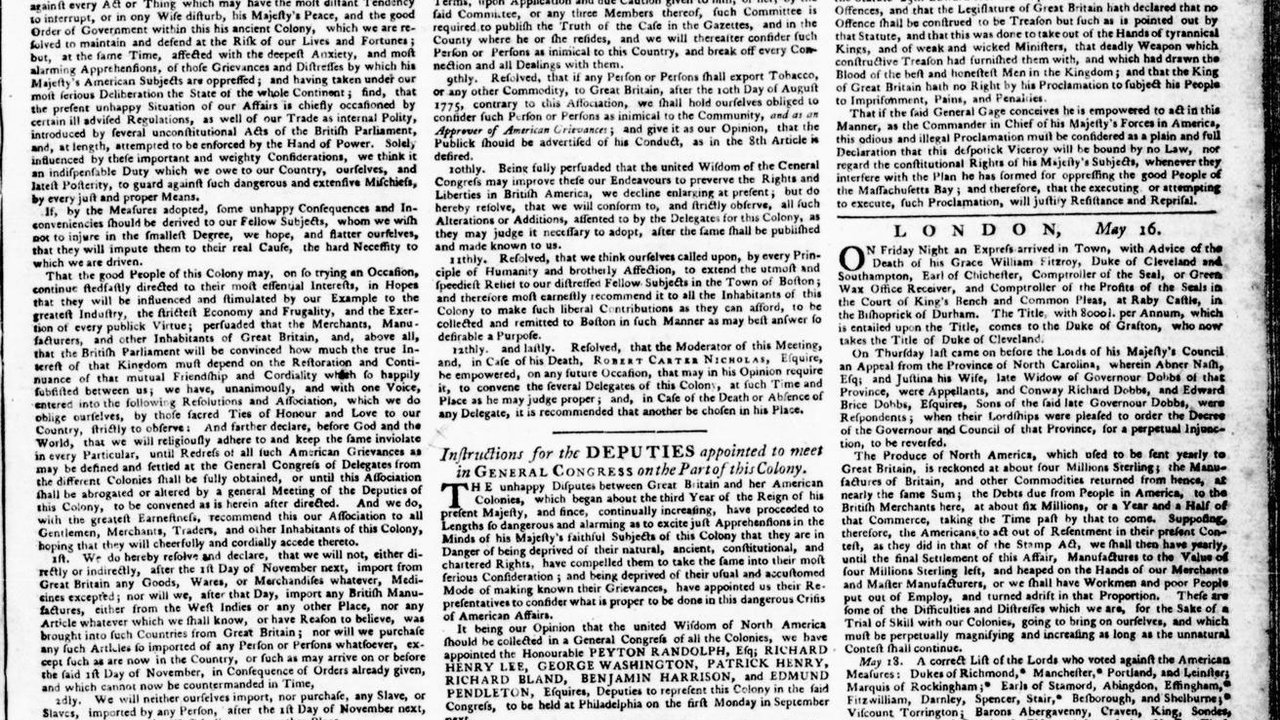

Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon)

Based largely on the Fairfax Resolves, the articles of the First Virginia Association were printed on the front page of the Virginia Gazette on August 11, 1774. Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Aug. 11, 1774.

The Fairfax Resolves provided a template for future resistance. When the First Virginia Convention opened in August, Washington brought the Fairfax Resolves with him to Williamsburg. The delegates adopted a plan for economic resistance to Parliament that included many features of the Fairfax resolutions. Once the colonists elected representatives to a Continental Congress, Virginia’s leaders pushed for an intercolonial system of economic resistance based on the Virginia’s convention’s resolutions.14 The Fairfax Resolves thus laid the groundwork for the Continental Association of 1774, the most far-reaching system of boycotts during the American Revolution.15 Echoing from the banks of the Potomac to Williamsburg to Philadelphia, the Fairfax Resolves played an important, but often forgotten, role in America’s road to independence.

Explore More Moments in History

History unfolds one day at a time. And every moment from our past tells a story. How did ordinary people navigate a world of colonialism, slavery, and revolution? How did colonists come to defy the social order? How did they build a new one? Dig into these stories to learn more.

Sources

- Jeff Broadwater, George Mason: Forgotten Founder (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 269n45.

- Donald M. Sweig, “A New-Found Washington Letter of 1774 and the Fairfax Resolves,” William and Mary Quarterly 40 (April 1983): 283–91. The Resolves were largely drafted by July 11, when Washington wrote a letter to his brother describing them. Mason spent the night of July 17 with Washington at Mount Vernon, giving them an opportunity to polish the draft. Once they arrived in Alexandria together the next morning, the Resolves were “revis’d, alterd, & corrected in the Committee,” according to Washington, before being submitted to the county’s voters. “From George Washington to Bryan Fairfax, 20 July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-10-02-0081.

- “Fairfax County Resolves, 18 July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-10-02-0080

- “Fairfax County Resolves”; Robert Scribner, ed., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, vol. 1: Forming Thunderclouds and the First Convention, 1763–1774 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1977), 110. Language like this comparing the oppression of colonists to slavery was common in revolutionary texts. F. Nwabueze Okoye, “Chattel Slavery as the Nightmare of the American Revolutionaries,” William and Mary Quarterly 37 (Jan. 1980): 3–28; Bernard Bailyn, Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1992; 1967), 232–46.

- The third resolution commented that colonists had failed to resist Parliament’s earlier efforts to regulate their trade “to avoid Strife and Contention with our fellow-Subjects.” “Fairfax County Resolves.”

- “Fairfax County Resolves.”

- “Fairfax County Resolves.”

- “Fairfax County Resolves.” For the benefit of the many aspirational and genteel Virginians who were deeply indebted to London merchants, resolution nineteen indicated that if they ceased exports, they could also stop paying their debts. Bruce A. Ragsdale, A Planters' Republic: The Search for Economic Independence in Revolutionary Virginia (Madison: Madison House, 1996), 194–95; Woody Holton, Forced Founders: Indians, Debtors, Slaves, and the Making of the American Revolution in Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1999), ch. 4.

- See resolutions 16, 20, and 21 in “Fairfax County Resolves.”

- “Fairfax County Resolves.”

- Holton, Forced Founders, 66–73.

- “Virginia Colony to George III of England, April 1, 1772, Petition Against Importation of Slaves from Africa,” Library of Congress, accessed June 14, 2024. John Pendleton Kennedy, ed., Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1770-1772 (Richmond: 1906), 257, link.

- “Fairfax County Resolves, 18 July 1774.”

- Ragsdale, Planters' Republic, 205. Similarities between the Fairfax Resolves and the Association of the Virginia Convention shared many provisions including agreeing to non-importation, ending the slave trade, ceasing the consumption of tea, boycotting the British East India Company, collecting for the Boston poor, refusing to grow or export tobacco unless grievances were redressed, and improving American self-sufficiency. Both also included rigid enforcement measures.

- Scribner, ed., Revolutionary Virginia, 1:230; Broadwater, George Mason, 67; Ragsdale, Planters’ Republic, ch. 7.