When studying a period long before video and voice recording was possible, it can be difficult to determine exactly what was said and when.

After several hours of close battle on September 23, 1779, carpenter John Gunnison and gunner’s mate Henry Gardner decided they had had enough. The armed merchant-ship Bonhomme Richard was leaking badly and most of her guns had been knocked out of action. The two men went on deck and found themselves in a charnel house: Bonhomme Richard’s deck was littered with dead and wounded, shattered timber, and torn rigging were strewn everywhere, the colors had been shot away, small fires smoldered, and cannon smoke hung over the ship. The captain was nowhere to be seen. Hoping to save what few lives remained, Gunnison and Gardner shouted across to the British warship Serapis that they wanted to surrender their vessel.

At that moment, Captain John Paul Jones, enraged at the apparent cowardice of his warrant officers, leapt up from behind a cannon he had been trying to train on the enemy mainmast, aimed his pistol at Gardner, and pulled the trigger ... only to discover it had already been fired. Jones then hurled the pistol at Gardner’s head, which knocked him out, and chased Gunnison below. Meanwhile, Captain Richard Pearson of Serapis had heard the attempted surrender. He called out to the battered Continental warship, “Have you struck? Do you ask for quarter?” Jones shouted back in defiance, “I have not yet begun to fight!”

How do we know that? There were no video cameras or tape recorders in 1779 to capture Jones’s words to his British counterpart. Welcome to one of the more challenging aspects of historical research: trying to find out exactly what happened, when it happened, and why it happened. Recordings aside, it is still possible to examine logbooks, newspaper articles, letters, and other sources from 1779 and get an idea of what Jones might have said in the heat of battle. For a variety of reasons, some sources are more reliable than others. For example, Jones’s quote above comes from a book published in 1825 “from original documents in the possession of John Henry Sherburne.” Sherburne had also spoken with Commodore Richard Dale, veteran of the American Revolution and the early United States Navy, and second-in-command to John Paul Jones during the battle with Serapis. According to Dale, “Jones himself answered, ‘that he had not yet begun to fight.’” While Dale was in a good position to hear what Jones had said at the time, Sherburne’s book was written nearly forty years after the battle and it’s entirely possible that his memory hadn’t perfectly recalled the moment after so long.

So where do we look for more information? Fortunately, both Jones and Person wrote official reports describing the battle. Unfortunately, neither of them provides an exact quote. In his report to Benjamin Franklin (an American commissioner in France who was instrumental in acquiring Bonhomme Richard for Jones) dated October 3, 1779, Jones wrote:

“The English Commodore Asked me if I Demanded Quarters And I having Answered him in the most determined Negative They renewed the Battle with redoubled Fury.”

One would imagine that Jones would be among the most reliable sources, but even he doesn’t give his exact words, though “I have not yet begun to fight” certainly sounds like “the most determined Negative” to me. Captain Pearson of the vanquished Serapis was no help either. In his own report sent from Texel in the Netherlands on October 8, 1779 (reprinted in the March 18, 1780 issue of the Virginia Gazette), Pearson wrote that he had “called upon the Captain to know if they had struck, or if he had asked for quarters; but no answer being made, after repeating my words two or three times, I called for the boarders, and ordered them to board.” In other words, the person supposedly on the receiving end of Jones’s famous line seems not to have heard him.

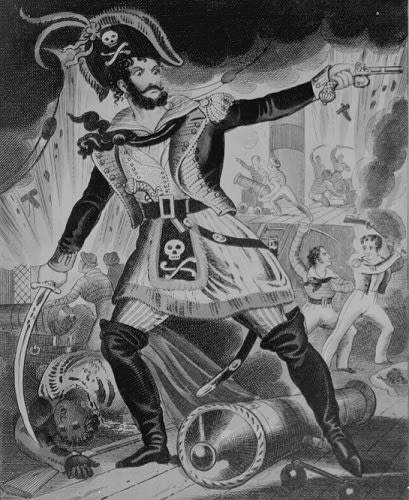

Bonhomme Richard defeated Serapis near Flamborough Head in northern England, and Jones had cruised in the vicinity of the British Isles since early 1778. As he had raided British merchant shipping, captured the sloop-of-war Drake, and conducted an amphibious raid on Whitehaven, the British press painted a fearsome image of Jones as a reincarnation of Blackbeard; the mere mention of Jones’s name was used to frighten misbehaving children. The October 12, 1779 issue of the Edinburgh Advertiser offered other details of the iconic moment which “may be depended upon as authentic.” According to this account, when Captain Pearson hailed Bonhomme Richard, “Jones replied, with an oath, ‘I may sink, but I’ll be d----d if I strike.’ At this instant, one of his men attempted to strike the colours, when Jones, turning round, shot him dead on the spot. Two more attempted the same thing and met with the same fate.” While newspaper articles like this one often “may be depended upon as authentic,” there was no investigative reporting in the 1700s as we know it today. It’s important to note that the witness of Jones’s words and the murder of his three crew (Gunnison and Gardner likely among them) was not identified, nor is it disclosed how these details came to the Advertiser. A lot of eighteenth-century news was hearsay, and often tailored to better entertain a paper’s specific readers. Even though Jones’s words qualify as “the most determined Negative,” his frequent appearance in British propaganda casts some doubt on this account.

With the excerpt from the Edinburgh Advertiser in mind, there are important questions to ask. Why was a given source produced? Is it a biography written decades after the fact? Is it a military after-action report giving official details of a battle? A source could even be an autobiographical memoir written to further the subject’s career.

Speaking of which, Jones provided another account of the battle in 1785. At that point, the Continental Navy had been disbanded, their few surviving ships had been sold out of the service, and Jones was out of work. Hoping to gain another naval commission (preferably as an admiral), Jones wrote a memorial to King Louis XVI of France. In it, Jones claims to have told Captain Pearson, “Je ne songe point a me rendre, mais je suis determine a vous faire demander quartier.” Roughly translated, “I haven’t as yet thought of surrendering, but I am determined to make you ask for quarter.” It has the meat of “I have not yet begun to fight” with some extraneous genteel resolution added for good measure, likely to show the King how cultured Jones was. Whether Jones really spent that much time telling Person “no” in the middle of a battle is another story.

An even more verbose depiction of Jones’s words comes from an 1805 memoir of Nathaniel Fanning, who served as a Midshipman during the battle with Serapis. Supposedly, Fanning also heard Person ask if Jones had surrendered:

“‘Ay, ay,' said Jones, 'we'll do that when we can fight no longer, but we shall see yours come down the first; for you must know, that Yankees do not haul down their colours till they are fairly beaten.’”

(The word “yankee” had been used by the British to describe Americans as early as 1758.) During the battle, Midshipman Fanning was said to have had command of the main top, a work and fighting platform suspended a good forty feet up Bonhomme Richard’s mainmast. Significantly farther forward and higher up than Jones was at the time, it is unlikely that Fanning reliably heard Jones, distracted as he was by sailors and marines firing muskets and throwing grenades all around him.

In the end, I’ve examined six sources that offer six possibilities as to how John Paul Jones responded to Captain Pearson in the heat of battle, and we still don’t have a definitive response. While “I have not yet begun to fight” is an excellent line in and of itself, there’s not enough reliable documentary evidence to suggest those were Jones’s exact words. And that’s perfectly fine. One of my favorite parts of being a historic interpreter isn’t necessarily being able to present every bit of historical minutiae beyond the shadow of a doubt but showing people why history is relevant. What’s more important: the exact words John Paul Jones shouted to Richard Pearson or that Jones refused to surrender and eventually defeated a British warship that outmatched his own in almost every way?

I’m inclined towards the latter. Whatever his exact words were, John Paul Jones showed people throughout Europe and America the best of what the Continental Navy was made of, and the lengths which American sailors would go to when their freedom was at stake. The fact that the present-day U.S. Navy has warships named for John Paul Jones and Bonhomme Richard show that Jones’s courage in battle and his ultimate victory are well worth remembering more than two hundred years after the fact.

Michael Romero is a Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter working in both Orientation and Public Sites. Since 2016, he has been working to bring 18th-century naval history to life. Michael has published work in Naval History magazine and NAI’s Legacy and is working toward a master’s degree in Military History from American Public University.

For Further Reading

- Fanning, Nathaniel. Fanning’s Narrative: Being the Memoirs of Nathaniel Fanning, An Officer of the Revolutionary Navy, 1778-1783. New York: De Vinne Press, 1912.

- Sherburne, John Henry. The Life of Paul Jones. London: John Murray, 1825.

- Thomas, Evan. John Paul Jones: Sailor, Hero, Father of the American Navy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003.