1. Superstitious Medical Practices

Eighteenth-century professional medicine was heavily influenced by the science of the Enlightenment. While superstitious beliefs were not promoted in the professional textbooks, practitioners occasionally mention details when they encountered them.

In 1735, John Atkins comments about fetishes in his book, “A Voyage to Guinea, Brasil, and the West-Indies.” He notes that a British Naval surgeon saw a prominent person wearing fetishes on his wrists and neck for their perceived medical effect.

In 1785, George Motherby wrote in his dictionary that the history of amulets and charms dated to ancient times. The appeal was that they did not offend the palate, were cheap, and one could indulge in superstition. He also notes that some patients thought that their practitioners had a connection with a superior being. This connection was used to impress and persuade patients to believe in the power of the charms. Motherby noted, “…as the mind affects the body, so in some cases the persuasion of the patient might contribute to a cure.”

2. Ordering Medical Supplies

There are some extant records of Dr. William Pasteur’s correspondence with Mr. Wellings in London asking for specific items to be shipped to Williamsburg. Very few of the ingredients in period pharmacy books were native to the American colonies. Most of the supplies were sourced internationally and shipped from England to the colonies.

A significant number of drugs were imported from the Far East by the Dutch East India company. One of the key trading ports was Batavia, known today as Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia.

3. Smallpox

Smallpox was a highly contagious international public health issue. It was estimated in the 18th century that the mortality could be as high as 20 percent. Quarantine procedures involved keeping patients isolated until their scabs fell off.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, it takes approximately four weeks from the time that symptoms appear until the scabs fall off, at which time patients are no longer contagious.

4. Cleanliness

The connection between cleanliness and health was determined empirically in the 18th century. It was not until the germ theory in the 19th century that science was able to explain the dynamics. While the word “clean” is seen in period texts on occasion, one does not often see written directions for washing hands.

Period doctors believed that the smallpox contagion could reside on surfaces. Today we know this is true. Dr. William Buchan wrote in the 1770s that people should wash their hands and clothing to prevent the spread of the smallpox contagion.

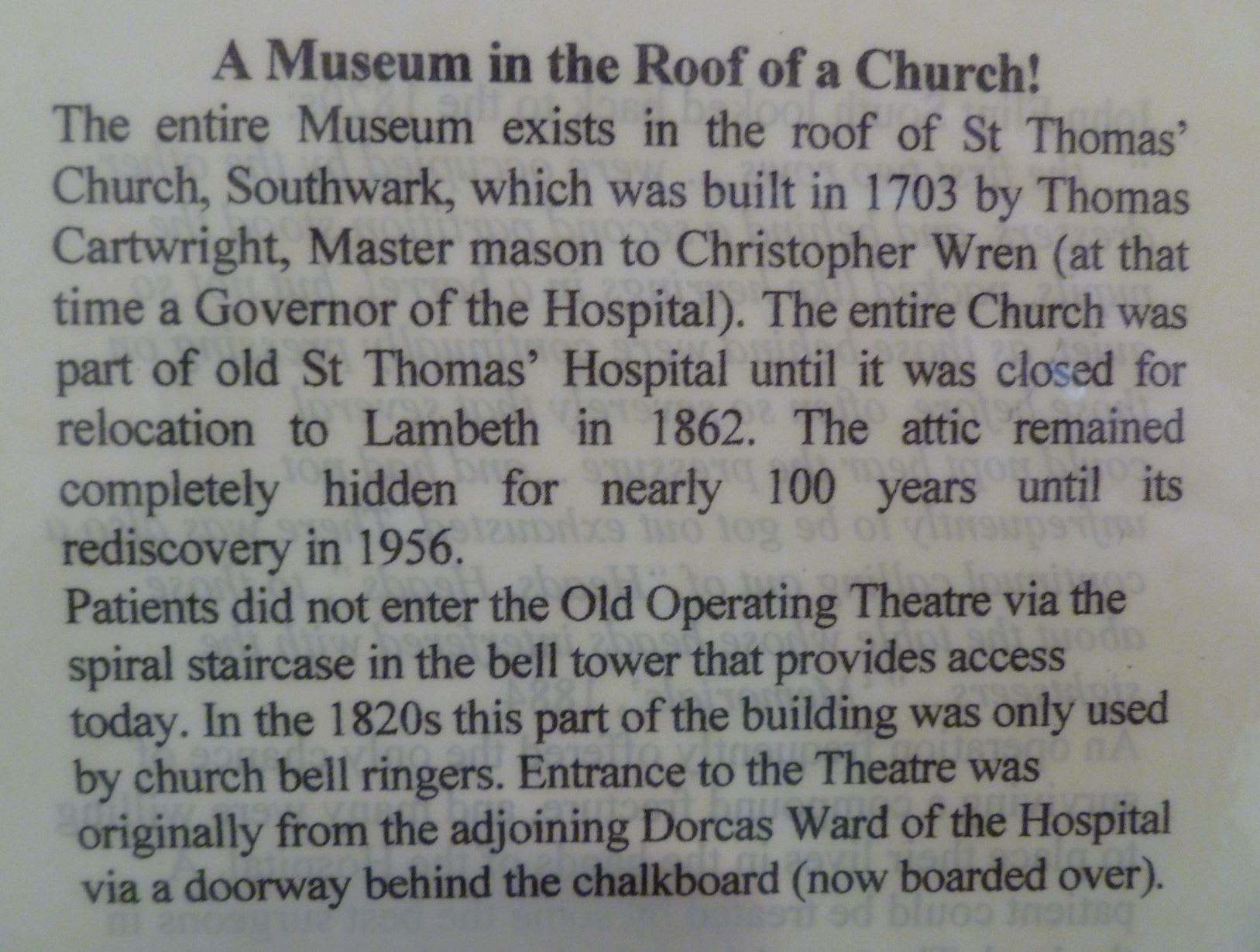

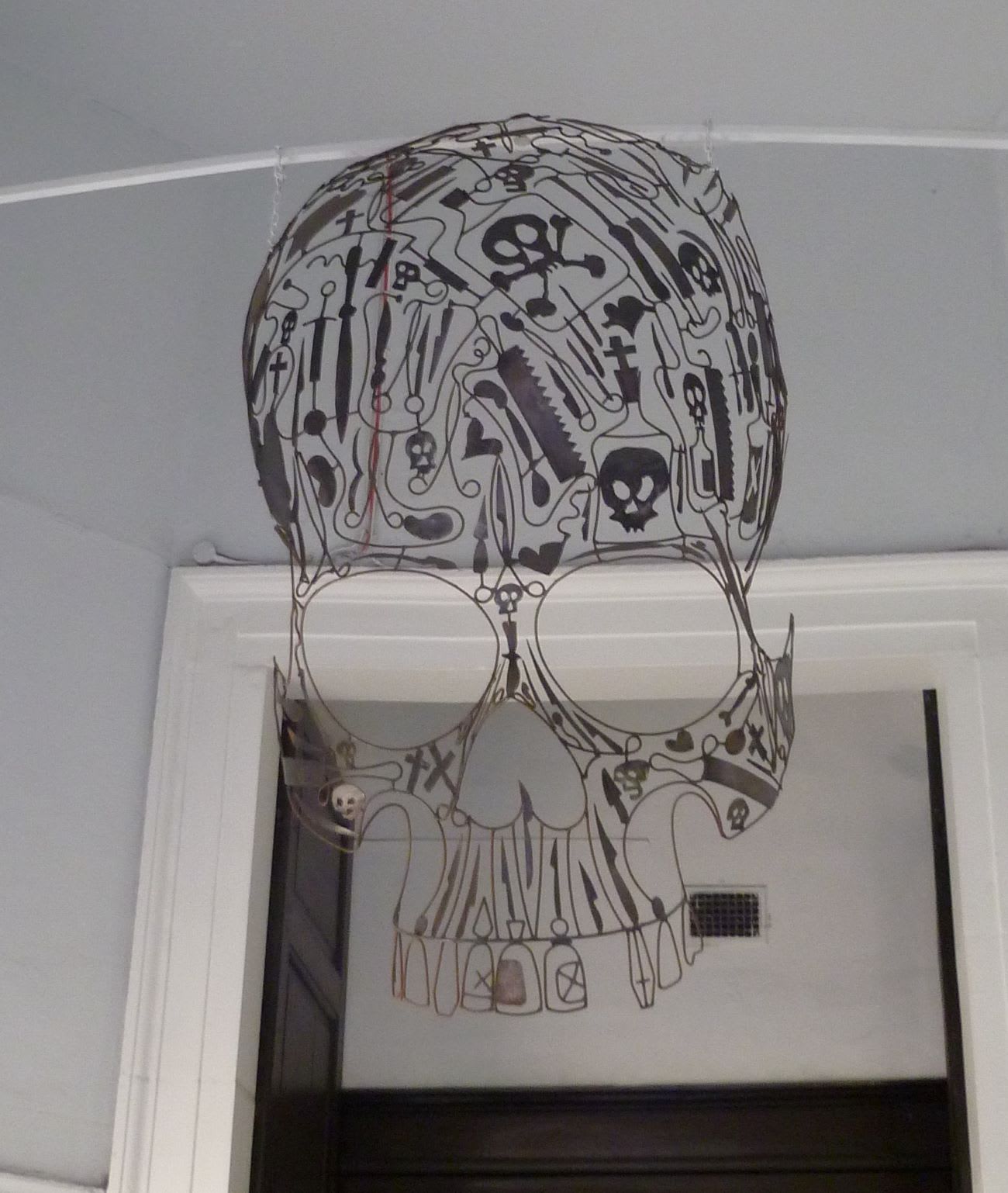

5. Saint Thomas’s Hospital

In the 18th century, the traditional method for studying pharmacy and surgery was through an apprenticeship. Some students pursued additional training in London. When John Galt finished his apprenticeship, he traveled to London to study at Saint Thomas’s Hospital.

Established around 1100 in London, St. Thomas’s Hospital was a charity hospital and trained medical practitioners in the 18th century. Several years after he returned to Williamsburg, Galt formed a partnership with William Pasteur.

A copy of John Galt’s certificate from this hospital is on display at in our historic Pasteur & Galt Apothecary shop. Today, the hospital is still in business and one of their 19th-century operating theatres is a museum.

Robin Kipps is the Supervisor of the Pasteur & Galt Apothecary. One of her favorite things to do is camping with her husband in their vintage travel trailer.