The founding fathers’ understanding of a free press has a long history and is one that we inherited under English law, but that doesn’t mean that England always had a free press.

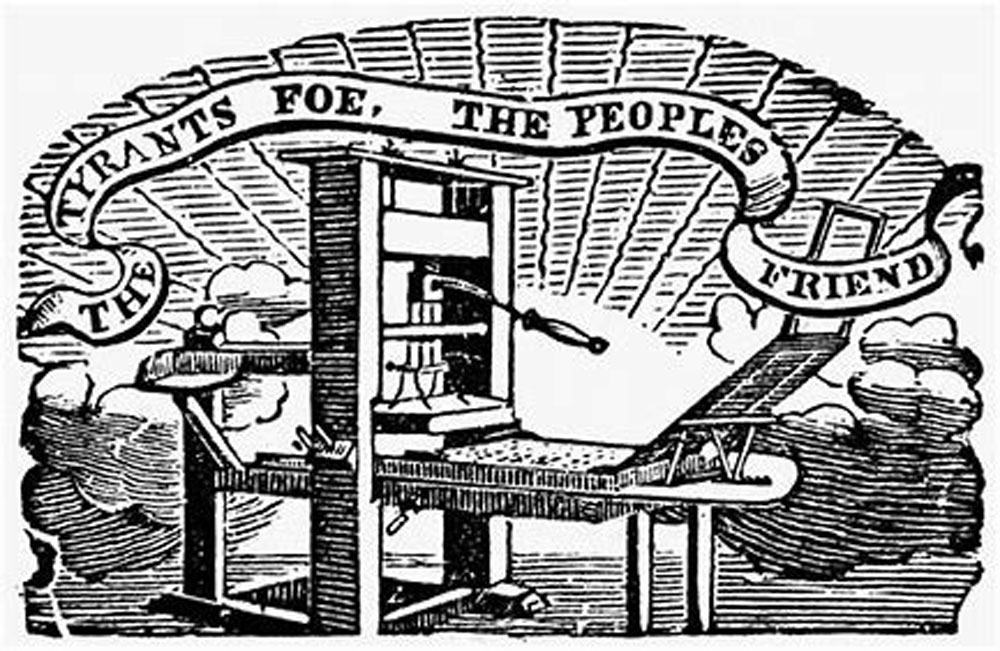

Starting in the year 1534 England, wrote into its laws what would become known as the Licensing Laws. These laws demanded that all presses in England be Licensed. The first press brought into America went to Cambridge, Massachusetts in the year 1639 by the Rev. Joseph Glover. Rev. Glover traveled to England to buy a press and hire a printer by the name of Stephen Daye to work with him. Unfortunately, Joseph Glover died on the voyage back to the colonies. The printer that he hired, Stephen Daye, secured the press and was granted the right by the elders of Massachusetts to run it and thus the American printing industry was born.

In the year of 1644, the first real push against the Licensing Laws came from John Milton in his pamphlet entitled “Areopagitica; a speech of Mr. John Milton for the liberty of unlicenc'd printing, to the Parliament of England,” yet it was not until the year of 1694 when the Licensing Laws were repealed — but not without restriction. With the lifting of the Licensing law, the Seditious Libel Law came into play. This law stated that it is a crime to publish anything disrespectful of the King, State, Church or their Officers. In the year 1734, a printer by the name of John Peter Zenger of New York, challenged that law when he was brought up on charges of Sedition, John Peter Zenger v. New York governor William Cosby in 1734, his defense in short, Truth is a defense against libel. Zenger won his case.

Eight years later in 1742, David Hume wrote about the British press, “Nothing is more apt to surprise a foreigner than the extreme liberty which we enjoy in this country of communicating whatever we please to the public and of openly censuring every measure entered into by the king or his ministers.” and went on to say “As this liberty is not indulged in any other government, either republican or monarchical—in Holland and Venice more than in France or Spain—it may very naturally give occasion to the question: “How it happens that Great Britain alone enjoys this peculiar privilege?” And whether the unlimited exercise of this liberty be advantageous or prejudicial to the public. The reason why the laws indulge us in such a liberty seems to be derived from our mixed form of government, which is neither wholly monarchical nor wholly republican. It will be found, if I mistake not, a true observation in politics that the two extremes in government, liberty and slavery, commonly approach nearest to each other; and that, as you depart from the extremes and mix a little of monarchy with liberty, the government becomes always the more free, and on the other hand, when you mix a little of liberty with monarchy, the yoke becomes always the more grievous and intolerable.” This still did not mean we had the right to openly speak out against the King, but could debate policy.

As all this was happening throughout England and her colonies, Virginia, in the year of 1683 a printer by the name of William Nuthead moved to Jamestown and attempted to become her first printer. The Royal Governor Sir Thomas Culpeper and his council took offense to this, so he wrote to the King for guidance (remember this was before the Licensing laws were lifted).

King Charles II’s response specifically prohibited printing in Virginia. This allowed Maryland to have an operating printing office before Virginia and Nuthead moved and set up his shop in St. Mary’s City. Virginia had to wait 47 more years before it saw its first real printer. In 1730 William Parks, from Maryland, moved to Williamsburg to set up his printing office. In June 1732, Parks was granted the first commission as “Printer to the Colony of Virginia” and by the 1760s, Virginia had two operating printing offices. Within the 13 colonies there were 24 weekly newspapers. With so many printers throughout the colonies it opened the door for satirical attacks on the government which became commonplace, with Virginia a willing participant.

Things started to heat up in the colonies’ presses throughout the 1760s, from the Sugar Act in 1764 to the Tea Tax in 1773 and beyond. One of the best examples of this type of satire that I can think of is “A pretty story written in the year of our Lord, 1774, by Peter Grievous, Esquire, A.B.C.D.E” by Francis Hopkinson, first published in Pennsylvania in 1774 and reprinted by John Pinkney in his Virginia Gazette, as well as in book form with the sales going to the benefit of the Rind children after Clementina Rind passed away.

The presses in both Williamsburg and Norfolk openly denounced the Royal Governor’s involvement in the “Gun Powder Incident”, when on April 20, 1775 in the middle of the night the governor took the colonies powder. This event took place the day after the first shots were fired at Lexington and Concord on April 19. By September 30, 1775 when the press in Norfolk was seized the colonies were in open revolt. The Battle of Bunker Hill had already been fought on June 17 and The King issued his Proclamation on August 23, 1775 declaring the colonies out of his protection, the Royal Governors were told to take charge of their colonies. John Hunter Holt’s newspaper the “Virginia Gazette or the Norfolk Intelligencer” challenged the Seditious Libel Law repeatedly from the time it started in 1774 till the time it was taken over by Governor Dunmore. A year later, in September of 1775, Holt used language referring to the British navy as pirates. Dunmore wrote a letter telling Holt to be fair in his reporting or else. The very next issue on September 27, Holt poked fun of Dunmore and his family; for Dunmore that was the last straw and he sent out a party of Marines to seize Holt. Holt hid and the marines seized his press, types, paper, and two workers. The governor thought that he would use the equipment on board his ship to print his own newspaper and bring balance back to the press. This story is accounted in Alexander Purdy’s Virginia Gazette of October 17, 1775. This act by Dunmore would be one of the leading reasons for Art. 12 of the Virginia Declaration of Rights to be written.

Of the original 13 States new laws we find that only seven of them and Vermont (The Vermont territory was claimed by both New York and New Hampshire but declared itself independent) will see freedom of the press and speech important enough to write into those laws. Here is a list of the States and how the law was written in their Constitutions or Bill of Rights going from north to south.

- A Declaration of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. - June 15, 1780: XVI.--The liberty of the press is essential to the security of freedom in a state: it ought not, therefore, to be restrained in this Commonwealth.

- A Declaration of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the Commonwealth or State of Pennsylvania - September 28, 1776: XII. That the people have a right to freedom of speech, and of writing, and publishing their sentiments; therefore the freedom of the press ought not to be restrained.

- A Declaration of Rights, and the Constitution and Form of Government agreed to by the Delegates of Maryland, in Free and Full Convention Assembled. - November 11, 1776: XXXVIII. That the liberty of the press ought to be inviolably preserved.

- Virginia Declaration of Rights – June 12, 1776: XII That the freedom of the press is one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty and can never be restrained but by despotic governments.

- North Carolina, A Declaration of Rights, &c. - December 18, 1776: XV. That the freedom of the press is one of the great bulwarks of liberty, and therefore ought never to be restrained.

- An Act for Establishing the Constitution of the State of South Carolina. - March 19, 1778: XLIII. That the liberty of the press be inviolably preserved.

- Constitution of Georgia; February 5, 1777: ART. LXI. Freedom of the press and trial by jury to remain inviolate forever.

- A Declaration of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the State of Vermont – July 8, 1777: XIV. That the people have a right to freedom of speech, and of writing and publishing their sentiments; therefore, the freedom of the press ought not be restrained. (Vermont was not yet a state yet, but saw fit to set up a Declaration of Rights)

For those of you keeping track, States that did not mention anything about Free Press or Speech, in order from north to south, are: New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island and Providence Plantation, New York, New Jersey and Delaware. It’s interesting to point out that both Connecticut and Rhode Island never wrote a new constitution but keep their original charters given to them by King James II. (Connecticut used the Royal Charter “The Oak Charter” of 1662 and Rhode Island, the Royal Charter of 1663)

From the evidence that we have, it appears that our founding fathers understood the power of the press and its need to remain free of government control, for communication with their State and for greater communication amongst the new Nation. As the Virginia Declaration of Rights put it “That the freedom of the press is one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty and can never be restrained but by despotic governments.”

David Wilson is a Journeyman Printer in the Printing Office. When not reproducing original documents for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, he can be found Smoking tasty meats in his smoker, brewing beer, riding roll-a-coasters, model making, but more often than not just hanging with his cats and friends.

Resources

- British Library

- Historical Society of the New York Courts

- “Of the Liberty of the Press,” Essays Moral, Political, and Literary, 1742. by David Hume, (1711 to 1776) Scottish Professor of Philosophy, describing the status of a free press in the United Kingdom. Freedom of the Press in Eighteenth-Century England

- 4) Facsimile prints of “A pretty story written in the year of our Lord, 2774, by Peter Grievous, Esquire, A.B.C.D.E” and Alexander Purdy’s Virginia Gazette of October 17, 1775 by The Colonial Williamsburg Printing office. Originals are held in the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

- Columbia Law School, Software Freedom Law Center

- Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library

- Charter of the Colony of Connecticut1662

- Rhode Island Department of State, Rhode Island Royal Charter Granted by King Charles II, 1663, Identifier: C#00865

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.