If I had a nickel for every time someone inquired about why a woman would be working in an 18th-century Joinery, I’d have...lots and lots of nickels.

Don’t get me wrong, I love to hear this question. I have devoted my career to researching, learning, and teaching about working women in the pre-industrial period. The reason I make the nickel remark is this: most visitors to Colonial Williamsburg are very surprised to see a woman swinging a hammer in the joinery. But this is precisely the reason my colleagues and I are here: to share our complex history, including clarifying that women were very much a part of the economic founding of America and to debunk the idea that female participation in the workforce was limited to classical, and often erroneous, spheres of “women’s work.”

To clarify: there is absolutely nothing wrong with assuming that women did not work prior to the post-modern period. In fact, this is part of the grand cultural narrative, the overarching theme of women’s history: exclusion. This is what has been propagandized in American history lessons for generations, but it is simply not true. This mythos exists in our shared history for several reasons.

Firstly, the idea of men being “superior” to women is old, ancient, and rooted deeply in the psyche of Western thought. In ancient writings, women are discussed in peripheral and inferior terms. Plato and Aristotle share similar sentiments: while men and women might possess the same abilities, men possess them to a higher degree. These ancient thinkers philosophize that life should be separated into two distinct spheres, the public and private, and through exaggerated views on biological difference. Plato and Aristotle pontificate that men should rule the public sphere and women the private. Unsurprising to none, the words of these ancient thinkers are used as the blueprint for ideal political life, and thereby set the stage for female marginalization. This tradition continues with Western Liberal philosophical thought. Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, two oft-quoted epistemologists on humanity and economics, are known for catapulting Western thinking into the Enlightenment. They further degrade a woman’s place simply by excluding them from their most basic ideas. They suppress any ideas of equality despite their foundational schema that man cannot dominate over another man. Despite this theory being riddled with inconsistencies, in particular against minorities and women, it is the pillar that upholds Western capitalism and world market domination. It is the altar at which we pray: the idea that “commonwealths are erected by the fathers” and the rule of man is that those “abler and stronger,” white men, are best fit to lead. This sets a precedent: women should be excluded from the public realm due to their inferiority. These ideas become part of our grander social narrative as capitalism becomes the foundation of American society.

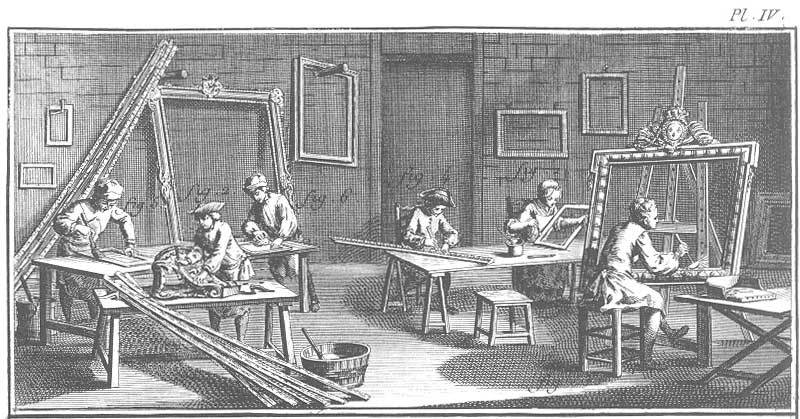

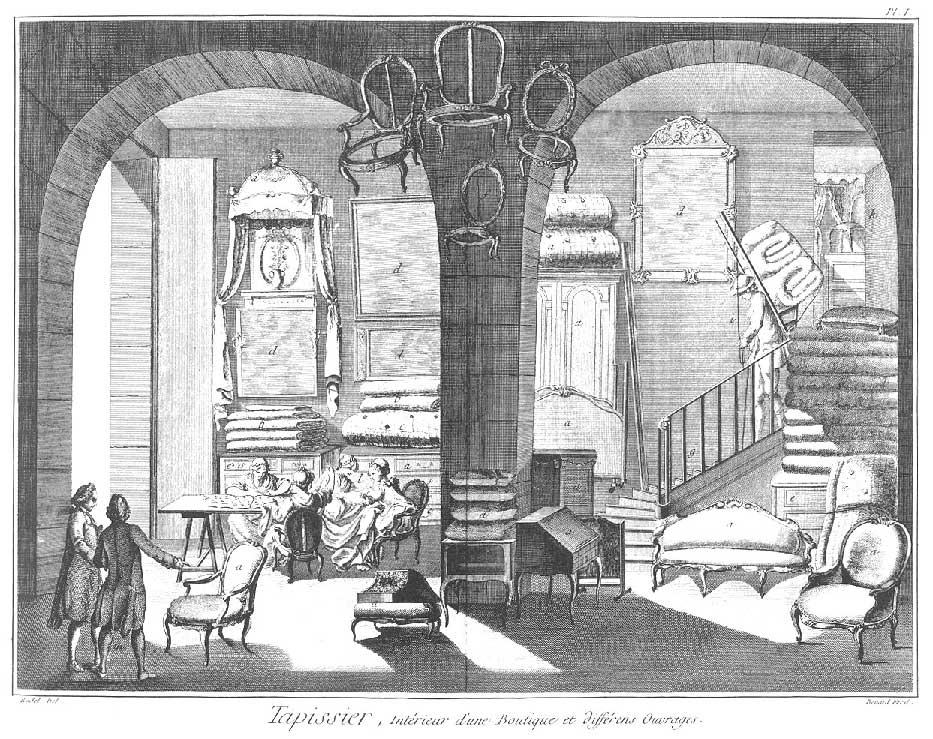

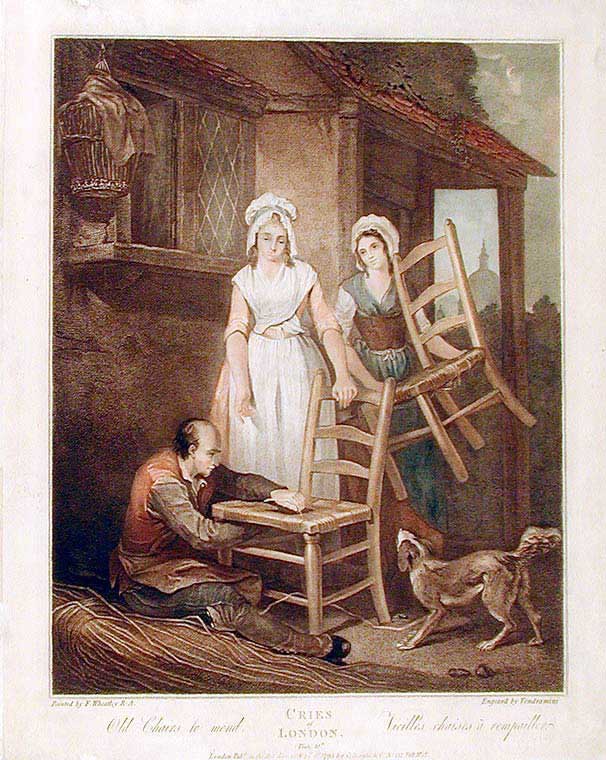

Secondly, the history often told in American mythos centers on the richest and wealthiest, not the common family. We tend to focus on the exceptional individual in history; in the study of American history, it is the Founding Fathers. These men represented the richest five percent of colonists, those we call the gentry. If these individuals were alive today, their wealth would classify them as millionaires and billionaires. This is important since it means that these families, the Washingtons, Jeffersons, Carters, Lees, and the like, were wealthy enough that one income could support their family. This is not the case for most colonial families or for families today for that matter. Most 18th-century families, that other 95 percent, could not support themselves with just the male head of household working and no one else creating revenue. Most free white Virginians fell into the Middling sort or Lower classes, meaning anyone who could work in some capacity would have to be gainfully employed. And this very obviously included women. We often say in our interpretation that there is nothing legal or social preventing a woman in the working class from performing a trade or participating in industry. We have records at Colonial Williamsburg of women working in nearly every trade, owning businesses, buying and selling goods at high rate for merchant practices, running taverns, printing a newspaper, and so on. If it is an aspect of colonial economics, women are very much present. Women, both formally and informally, are apprenticing in trades and are being mentioned in guild records in England as Mistresses of trades and taking on apprentices of their own. In fact, Diderot’s Encyclopédie includes portrayals of women working in more than 20 plates.

This sounds wonderful. Women were active participants in a consumer economy that lays the groundwork for creating America as an economic superpower. But there are lots of caveats here. Legally, an unmarried woman could own a business, own property, represent herself in court, and sue another person. Unmarried status classified a woman as “Femme Sole.” But here’s the rub: once a woman married, she becomes Femme Covert, or a “covered woman.” Her husband becomes her legal representative, now owns all her property, and the wife can own nothing. To further destroy any ideas of equality, women also earned less than men for equal work. In the building trades, for example, free white women earned somewhere around $.60 on the dollar to a man’s work. So, while it is extremely important to recognize the significant contribution to the economy that working women provided, it’s also important not to be misled. Women were still very much viewed as inferior through the lenses of Plato, Hobbes, and other misogynistic power players.

This narrative persists and indeed grows more robust on the eve of industrialization. In the late 18th century, the cultural soil is ripe to reap a world where white male domination persists, and indeed it does. Western economic domination is fully dependent on the enslavement of Africans and their children. A patrilineal monarchy controls a major portion of the world and the global economy. A new non-monarchical nation is forged post-Revolution by wealthy, white, male enslavers who control industry. At the start of the industrial revolution, white men have a very firm grip on power.

The point here is that our history is complex. It is understandable and okay to be surprised to find women working with their hands and participating in 18th-century industry, because their story has largely been omitted by the historical narrative. Despite women being active participants in the creation of our economy, their story is often excluded from the grand cultural narrative. Challenging our told cultural ideas can be jarring. But that is precisely why Colonial Williamsburg demonstrates female participation in trades; it is our job as a public history museum to tell the complete story to the best of our ability. We continue to research women’s history and roles in colonial America and look forward to sharing this information with our guests through our interpretation and programming. And as we continue through Women’s History Month, I challenge you to reconsider where you might envision a woman in the 18th century, why that is, and how these women contributed to our rich and varied culture.

Amanda Doggett is an Apprentice Joiner with the Historic Trades and Skills of Colonial Williamsburg. She is a 2011 Christopher Newport University graduate, as well as a Fellow with the International Center for Jefferson Studies. She began her career with Colonial Williamsburg in 2013, making the transition to trades in 2016. An avid runner and reader, Amanda lives in Yorktown with her partner Matthew and her coonhound Chuck.

To continue this discussion, please join us virtually March 20 at 4 p.m. EDT for the third installment of our national conversation series, US: Past, Present, Future as we discuss the lives and roles of Virginia women in the 18th-century and today.

Further Reading

Abramovitz, Mimi. Regulating The Lives Of Women: Social Welfare Policy from Colonial Times to the Present. 3rd ed., Routledge, Oxfordshire, 2017.

Brown, Kathleen M. Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1996.

Cleary, Patricia, “’She Will Be In the Shop’: Women’s Sphere of Trade in Eighteenth Century Philadelphia and New York.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 119, no. 3, 1995, pp.181-202

Gundersen, Joan Rezner. “The Double Bonds of Race and Sex: Black and White Women in a Colonial Virginia Parish.” The Journal of Southern History 52, no. 3 (1 August 1986), 351-72.

Kierner, Cynthia A. and Sandra Gioia Treadway, eds. Virginia Women: Their Lives and Times. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015

Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812. Vintage Books, New York, 1990

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.