Architectural preservation and research staff at Colonial Williamsburg are responsible for the care and scholarly interpretation of buildings in the Historic Area. This work includes preservation and stewardship of historic structures, design of new reconstructions, historic interiors, curation of the architectural collections, and ongoing research on the city's built and cultural environment.

Current Projects

Preserving and Restoring the Historic Area

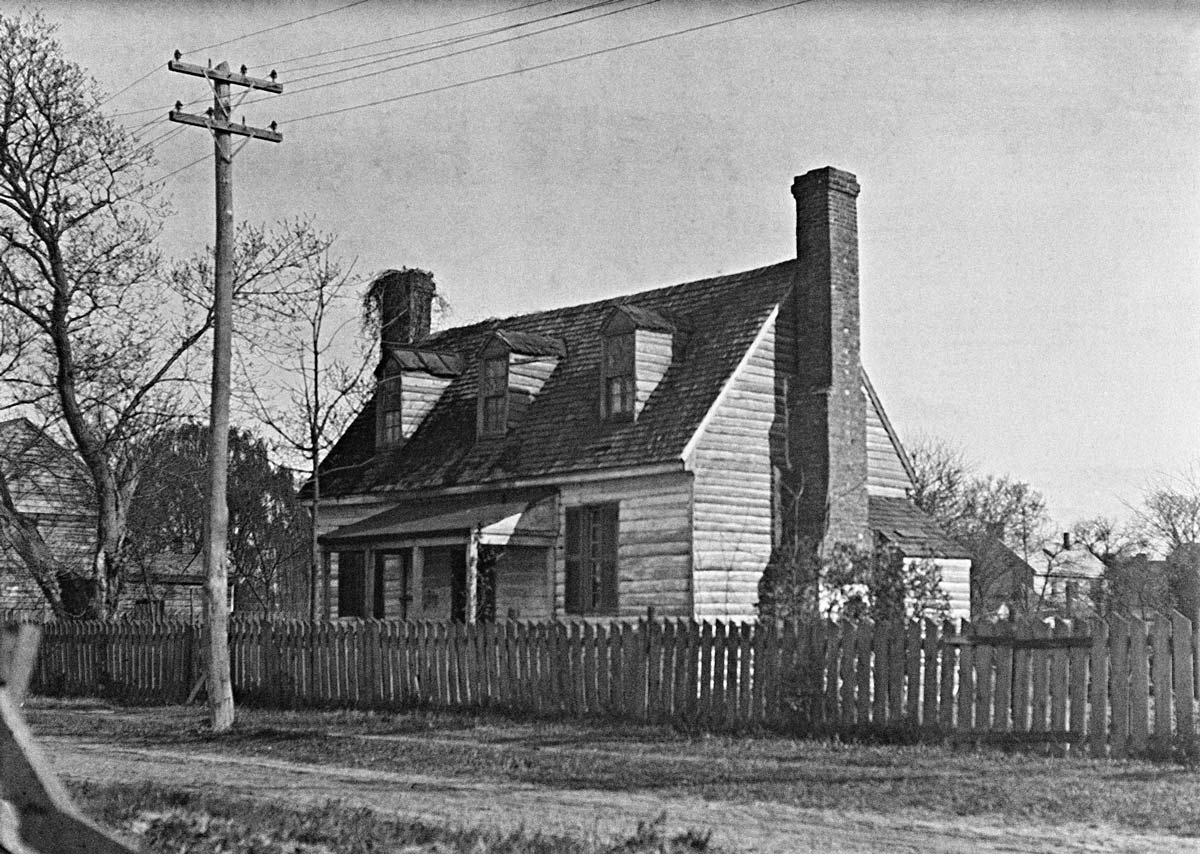

Williamsburg has not always looked as it does today. Beginning in the 1920s, before the Palace, the Capitol, or the Raleigh Tavern could be reconstructed, architectural historians needed to determine how those buildings looked in the 18th century. This information came from excavated foundations, from drawings and written descriptions, and from surviving 18th-century buildings in England and America. Most important, however, was Williamsburg's surviving architecture. Through close study of these buildings in their historic context and surviving 18th-century architectural fragments from 50 Historic Area buildings, we have learned—and continue to learn—what was distinctive about the architecture of this place, and how to aid in its restoration.

Overall, our chief responsibility is the care and scholarly interpretation of the Historic Area buildings. While we provide support for over 580 buildings in the Historic Area, we undertake in-depth maintenance on approximately 120 structures open to the public in one, two and three year cycles. The maintenance projects include a great deal of work, including carpentry repairs, painting, mechanical maintenance, conservation treatments, and curatorial changes. Closing a site for preventive maintenance requires meticulous coordination, since as many as two dozen trades may undertake work on a building during the project. Though much has changed over the decades, our work is still grounded in a combination of archaeological, documentary, and field research. Our stock-in-trade includes written analysis of historic buildings, measured drawings, and photographs. This research material constitutes an essential and growing archive on the early American built environment and informs both our written work and our reconstruction designs. We share this knowledge with our visitors through our restorations and reconstructions in the Historic Area.

Interpreting Our Buildings

Though we have learned much in more than 80 years of study, new analytical techniques—like dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) and cross-section paint microscopy—allow us to make fresh discoveries on familiar sites. We continue, for example, to learn about the application of color throughout Williamsburg, and some changes, like the repainting of the Peyton Randolph House red-brown, or the Robert Carter House a deep gray, have been quite obvious and sparked visitors' curiosity.

Other developments have been more subtle but equally significant, like the discovery, thanks to paint research and dendrochronology, that it was the gunsmith John Brush (1717), rather than mayor Thomas Everard (1751), who installed the ornamental stair at the Everard House; and that parts of the Robert Carter House survive from Robert “King” Carter’s ownership in the late 1720s, a whole generation earlier than we had previously believed.

Developing Historical Context

We also look beyond the buildings for relevant data, collecting information from archival sources like wills, estate inventories, and personal letters to help determine how spaces were used within each exhibition building. They guide us in our development of period-appropriate furnishing plans, setting the scene for our guests to become visually immersed in the lives of the people who lived here in the 18th century. In addition, surviving artifacts from the families and archaeological objects found on the sites are also invaluable sources that guide our ever-evolving interpretation of the exhibition spaces.

Special installations such as an 18th-century marriage celebration at the Thomas Everard House or a Subscription Ball at Wetherburn’s Tavern were brought to life through intensive research and skilled craftsmanship. Working with other foundation curators, conservators, and technicians, we are able to provide accurate reproductions of colonial attire and food services. For instance, the wedding dress made for the Everard installation, was designed based on a surviving colonial example and made by hand by our historic trades milliners, and the faux food used in the Wetherburn’s installation was carefully researched and hand-crafted by the foundation’s Historic Interiors Collections Care staff based on food prepared by our Historic Foodways trades people.

Working with others throughout the foundation, we are constantly planning new installations throughout the Historic Area. Through continued research and ever-expanding analysis, we are continuing to not only provide a scholarly interpretation of the buildings, but a rich visual and personal experience for our guests.

Learn More

Preserving Colonial Williamsburg Blog Posts