Closed currently

-

Monday

9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

-

Tuesday

9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

-

Wednesday

Closed

-

Thursday

Closed

-

Friday

Closed

-

Saturday

9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

-

Sunday

9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

What was it like to be the governor of Virginia? What was it like to serve him? The Governor’s Palace was home to seven royal governors, Virginia’s first two elected governors, and hundreds of servants and enslaved people. It was built to display the colony’s wealth, power, and permanence. Tours of the reconstructed building depart regularly from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.

Building and Furnishing the Palace

If building a Palace was easy, everyone would have one. But the governor’s house took longer to finish than anyone expected. The Virginia General Assembly agreed in 1705 to finance the construction of a “house for the governor.”1 But after five years of planning and construction, the building remained incomplete. Worried that an unfinished structure would be “to all strangers a visible testimony of an imprudent undertaking,” Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood pressed the assembly for more funds and eventually took charge of the construction himself.2

Spotswood had grand designs. Over time, the ballooning cost of the Palace’s construction raised questions among the gentry. The House of Burgesses eventually tried to have Spotswood removed from office, complaining among other things that he “lavishes away” the colony’s funds in constructing the governor’s home.3 They were particularly critical of his ambitious plans for the gardens, which included a canal, fishpond, and terraces.4 The Governor’s Palace gardens were among the most imitated and admired in the American colonies.

Construction of the building and grounds was partly funded by a tax on the importation of enslaved people into Virginia.5 At one point, the contractor in charge of construction of the building sold three enslaved people, who had been purchased as laborers, to purchase materials.6 The building was finally completed, at great cost, in 1722.

The Palace’s richly furnished interiors were designed to impress. We know a great deal about the furniture, decorations, and goods contained in the palace. After Governors Fauquier and Botetourt died in 1768 and 1770, inventories of their possessions identified thousands of items spread across the Palace’s 61 rooms. We also know many details about Governor Dunmore’s furnishings because his goods were sold at auctions after he fled the Palace in 1775. Some of these items now reside in the reconstructed Palace.7

Explore the Interiors

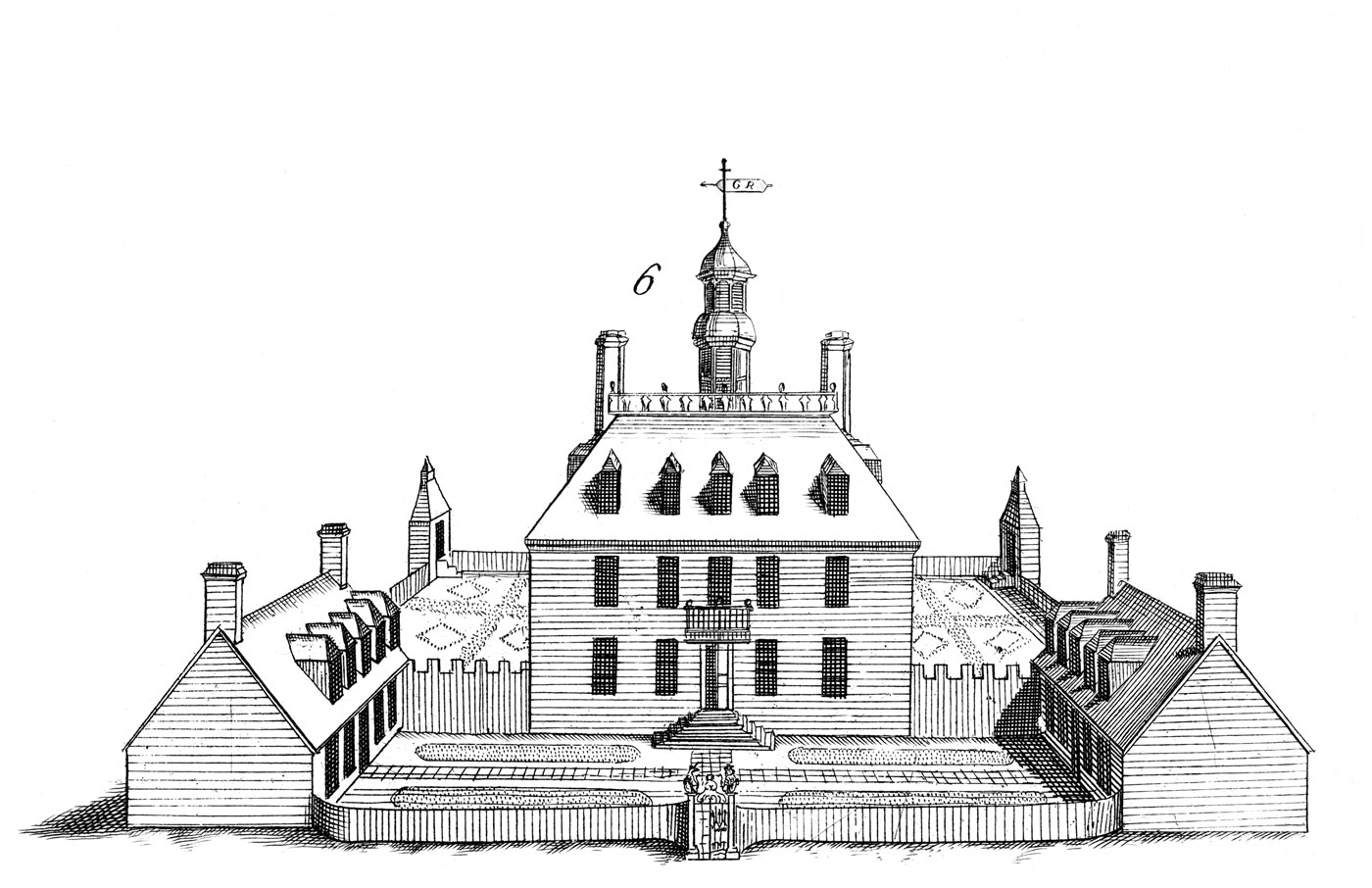

Visitors to Williamsburg generally admired the Palace’s Palladian architecture and graceful gardens. One observer remembered the Palace as a building which “far exceeded the Temple of Diana at Ephesus or that of the Sun at Palmyra” (which were two legendary ancient temples).8 Another traveler contrasted the Palace’s beauty with the simplicity of the rest of Williamsburg: “There is nothing considerable in” the town “but the College, the Governor's House, and one or two more, which are no bad Piles.”9

Go deeper: In the 1980s, furnishings in the reconstructed Governor’s Palace were updated to reflect the detailed estate inventory of Governor Botetourt.

The Governors and Their Families

For much of the eighteenth century, the Governor’s Palace could have been referred to as the Lieutenant Governor’s Palace. Its first five inhabitants were actually Lieutenant Governors, serving in the place of absentee governors.10 Of the building’s inhabitants, only Lords Botetourt and Dunmore were royal governors in their own right.

The Palace was built for ceremonial activities, but it was also a home. Like any home, it witnessed cycles of birth, life, and death. Three governors died in the building. When Lieutenant Governor Hugh Drysdale died in 1726, the colony’s Council assured his widow Hester Drysdale that “they desire she will please to continue in the Governor's house, and make use of any other Conveniences about it during her stay.”11

The governors’ families included a few children. The Gooch family raised their son William there. Governor Dinwiddie arrived in the colony with his wife Rebecca and two daughters, Elizabeth and Rebecca. Charlotte Murray, wife of Governor Dunmore, arrived in the Palace with six children. In December 1774, she delivered another child at the Palace, a daughter named Virginia in the colony’s honor.12

The Palace's Governors

-

Alexander Spotswood

1710-1722Spurred construction of the palace and designed its gardens. Came into conflict with Virginia gentry.

-

Hugh Drysdale

1722-1726Popular with Virginia gentry. Led colony through a period of relative peace and prosperity. Passed reforms to prevent insurrections of enslaved people.

-

William Gooch

1727-1749Promoted western settlement. Led a campaign against Spanish South America.

-

Robert Dinwiddie

1751-1758Led early stages of French and Indian War. Appointed George Washington to his first command.

-

Francis Fauquier

1758-1768Dissolved House of Burgesses in response to Stamp Act protests. Died in the palace.

-

Baron de Botetourt

1768-1770Popular Governor. Dissolved Burgesses in response to colonial protests. Died in the palace.

-

Earl of Dunmore

1771-1775Fled palace in 1775 due to political agitation. Last British colonial governor of Virginia.

-

Patrick Henry

1776-1779First elected governor of Virginia. An eloquent speaker and leading revolutionary.

-

Thomas Jefferson

1779-1781Socialized in palace under Gov. Fauquier. Presided over Virginia government's move to Richmond. Had planned to renovate Palace.

Servants and Enslaved People

The Palace was Williamsburg’s biggest household. At any given time, between twenty and thirty white servants and enslaved people lived and worked in the Palace.13 They worked not only in the main building, but also in the kitchens, the stables, coach house, the gardens, park, farm, and elsewhere. We also know that several enslaved children lived in the Palace complex.14

Go deeper: What do we know about the lives of the enslaved people and servants who resided at the Palace?

Visitors

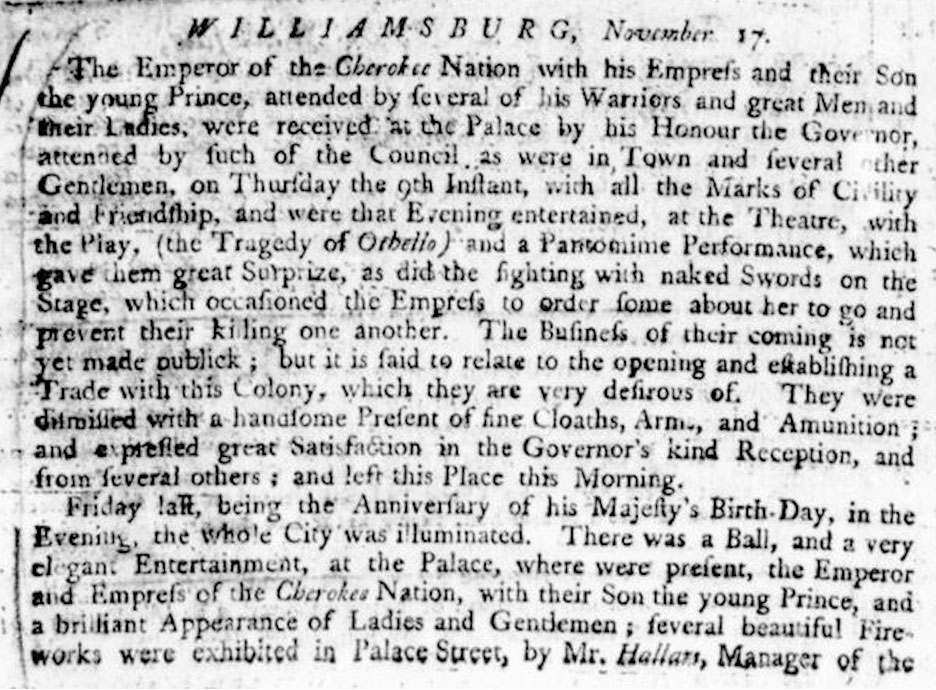

The Governor’s Palace was built to entertain. It hosted notable visitors, including English philosopher George Berkeley, the evangelist George Whitefield, and neighboring governors.15 Governors also conducted diplomacy with Native delegations at the Palace.

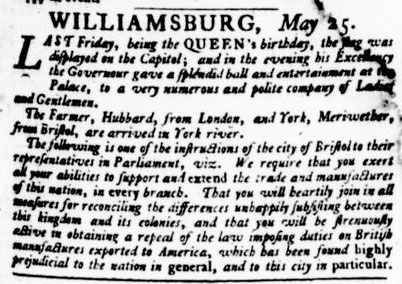

Prior to the revolution, Williamsburg marked the birthdays of kings and queens with an elaborate celebration at the Governor’s Palace. These events featured a ball, food, drinking, and fireworks.

Visitors Featured in the Virginia Gazette

American Revolution

By the mid-1770s, revolutionary colonists threatened the Palace. In April 1775, after Governor Dunmore seized gunpowder stored at the Magazine, his wife and family fled the Palace. They were more popular than the governor. A writer in the Virginia Gazette welcomed them back when they returned the next month and remarked that the “whole country” had the “most unfeigned regard for her Ladyship, and wish her long to live amongst them.”

Fearing that colonists would attack the Palace in retribution for seizing the gunpowder, Dunmore initially armed the Palace. But he and his family had fled the Palace by June. It was the end of royal government in Virginia.

Dunmore’s household possessions were unceremoniously auctioned off. The people of Williamsburg took possession of the Palace, and it became the residence of Virginia’s wartime governors Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry. After the capital city moved to Richmond, it was briefly used as a Revolutionary War hospital. The main building burned down in 1781, and the rest of the complex was either sold off or left to decay. 18

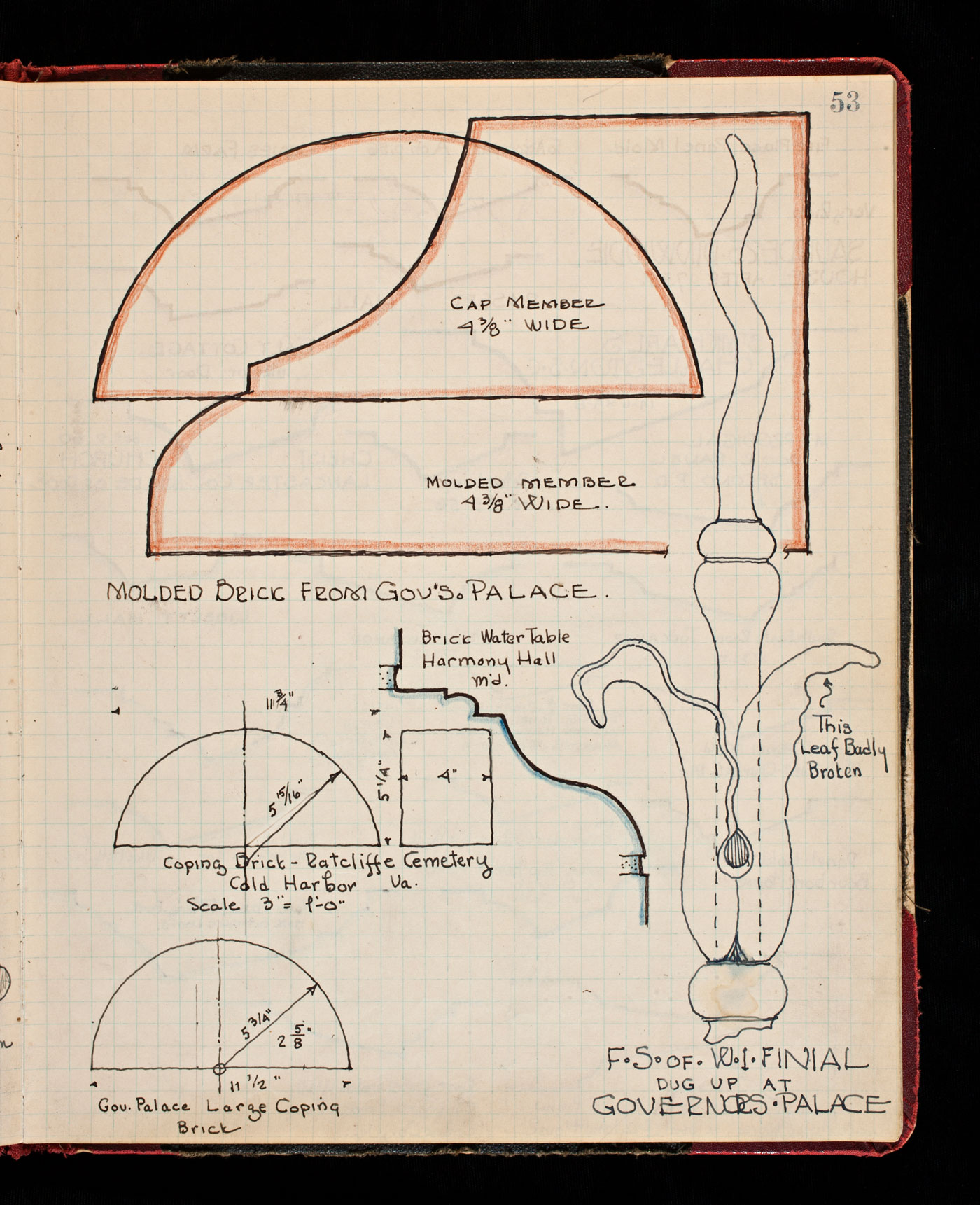

Restoration

Colonial Williamsburg reconstructed the Palace between 1931 and 1934. During their excavations, archaeologists discovered a cemetery while excavating the Palace grounds, likely created when the site served as a hospital during the Revolutionary War.19 The reconstructed building opened to the public on April 23, 1934.

Explore Virtually

Learn More

SOURCES

- William Waller Hening, ed., The statutes at large: Being a collection of all the laws of Virginia, from the first session of the legislature in the year 1619, vol. 3 (Richmond: Samuel Pleasants, 1812), 285. Link.

- H. R. McIlwaine, Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia: 1712–1714, 1715, 1718, 1720–1722, 1723–1726 (Richmond: Colonial Press, 1912), xxi.

- H. R. McIlwaine, ed., Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1712–1714, 1715, 1718, 1720–1722, 1723–1726 (Richmond: Colonial Press, 1912), 230. Spotswood responded that they needed to finance further construction or the investment in the house would be “spoyled” through exposure to the elements. He told them that while they saw it as “lavishing away the Country’s money,” he viewed it simply as a matter of “finishing what the Law has directed.” H. R. McIlwaine, ed., Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia, vol. 3 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1928), 498.

- Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 52–53.

- “The Governor's Palace: Historical Notes,” (1990), Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library, p. 23, 37, 69, 77, 93.

- H. R. McIlwaine, ed., Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1702/3-1705, 1705-1706, 1710-1712 (Richmond: Colonial Press, 1912), 232; H. R. McIlwaine, ed., Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia, vol. 3: May 1, 1705–October 23, 1721 (Richmond: Davis Bottom, 1925), 180.

- The inventories are reproduced in “The Governor's Palace: Historical Notes,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library.

- “Journal of Alexander Macaulay,” William and Mary College Quarterly vol. 11 (Richmond: Whittet & Shepperson, 1903), 186. Link.

- “Observations in Several Voyages and Travels in America in the Year 1736, (From The London Magazine, July, 1746.),” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine, vol. 15 (Richmond: Whittet & Shepperson, 1907), 223. Link.

- The absentee governors were the Earl of Orkney (1698–1737), the Earl of Albemarle (1737–1754), the Earl of Loudon (1756–1759), and Jeffery Amherst (1759–1768).

- H. R. McIlwaine, ed., Executive Journals of the Council of Virginia, vol. 4: October 25, 1721–October 28, 1739 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1939), 114.

- Mary Miley Theobald, “The Governour’s Lady: Mistresses of the Palace,” CW Journal (Spring 2003).

- Graham Hood, The Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg: A Cultural Study (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1991), 231.

- There are several references to enslaved children in the estate inventories of Governors Fauquier and Botetourt. See “The Governor's Palace: Historical Notes,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library, pp. 160–61, 163, 167, 170, 198.

- Hugh Jones, The Present State of Virginia (New York: Sabin, 1865), 31. Link.

- Stephen Hawtrey to Edward Hawtrey, March 26, 1765, in Florence Molesworth Hawtrey, The History of the Hawtrey Family (London: George Allen, 1903), 1:147. Link.

- William Q. Maxwell, “Palace Manual,” (1954) Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library, 55–56.

- A. Lawrence Kocher, “Architectural Report: Palace of the Governors of Virginia Block 20 Building 3,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library, 133–34.

- H. S. Ragland, “Governor’s Palace Historical Report, Block 20 Building 3,” (1930), Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library.

Come Explore In Person

-

Historic Site: Capitol

Rediscover the founding principles of our American government.

CW Admission

-

Historic Site: Peyton Randolph House

Take a guided tour to learn about the paradox of slavery in the Revolutionary period.

CW Admission

-

Historic Site: The Rockefellers' Bassett Hall

The Story Behind the Restoration

CW Admission

Handicap Accessible