Thomas Jefferson did not, of course, invent the idea of “establishing religious freedom.” Jefferson’s thinking was very much a product of the Enlightenment, when many in Europe and America gravitated toward the concept.

Indeed, other states were closer to Jefferson’s ideal than Virginia. Pennsylvania, most notably, had been founded by the Quaker William Penn and was more tolerant than Virginia of the many sects living there. And in 1776, the year before Jefferson drafted his bill, Virginia’s Declaration of Rights had asserted that “all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion.”

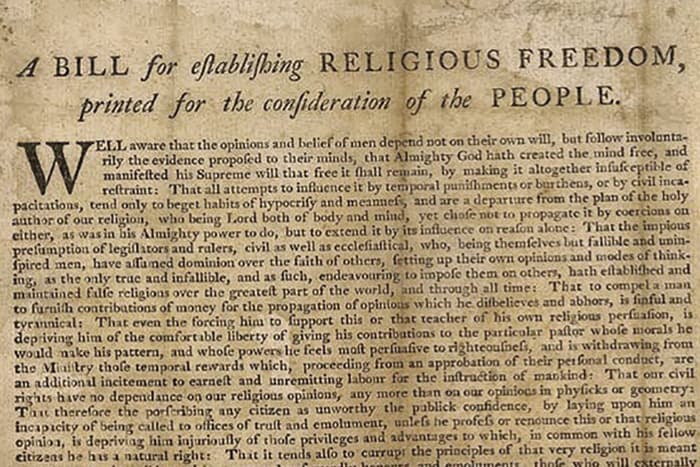

Yet Jefferson’s bill for establishing religious freedom, which was introduced in 1779 to the House of Delegates in Williamsburg, was the nation’s first attempt to codify religious freedom. It was, in the words of Anson Stokes, author of Church and State in the United States, “of epoch-making significance at home and abroad, as Virginia is believed to have been the first state in the world to have provided by self-imposed statute for complete religious freedom and equality.”

Jefferson’s bill was too radical for Virginia’s delegates in 1779, and it was tabled. Gradually, however, dissenters from Virginia’s official church (which was known as the Anglican Church before the Revolution and the Episcopal Church after) made strides toward equal rights. In 1780, for example, the legislature legalized marriages performed by dissenting ministers, such as Baptists and Presbyterians.

In 1784, Patrick Henry and others in the legislature proposed a “general assessment.” In one sense, this was a step toward religious toleration, since it meant the government would provide funds for all Christian sects and not just the Episcopal Church. But dissenters objected and called for a full separation of church and state. With Jefferson serving as minister to France, James Madison led the fight against the general assessment and that bill died.

Madison seized the opportunity to reintroduce Jefferson’s old bill and in January 1786 Jefferson’s words — with some edits — became law.

The bill opened with what retired Colonial Williamsburg historian Linda Rowe, writing in Becoming Americans: Our Struggle to Be Both Free and Equal, called a “ringing phrase:” “Almighty God that created the mind free.” By acknowledging God, Rowe pointed out, “Jefferson deftly combined religious and rationalist ideals. Both dissenters and enlightened thinkers could champion this symbol in the struggle to disassociate religion and government.”

The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom went on to proclaim that “no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer, on account of his religious opinions or belief, but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion.”

The Virginia Statute influenced similar provisions in other states and other nations, as well as the First Amendment to the Bill of Rights, which declared “Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion, or pro-hibiting the free exercise thereof.” Jefferson’s act, wrote historian Edwin Gaustad, “set Western Civilization and democratic republics everywhere upon a dramatically different path.”

Jefferson was extremely pleased his bill had finally passed. In August 1786, he wrote to George Wythe from Paris: “The ambassadors and ministers of the several nations of Europe resident at this court have asked of me copies of it to send to their sovereigns...I think it will produce considerable good even in these countries where ignorance, superstition, poverty and oppression of body and mind in every form, are so firmly settled on the mass of the people.”

Famously, Jefferson asked that his tombstone record two documents he authored: the Declaration of Independence and the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom.