On the morning of Dec. 2, 1785, Noah Webster hopped on his horse in Richmond, Virginia, to begin the 60-mile trek to Williamsburg. The 27-year-old former schoolteacher, who had fought in the Battle of Saratoga during his undergraduate days at Yale, was in the South to hawk his recently published blockbuster, a spelling book for schoolchildren. A clever marketeer, he had personally designed his own book tour — America’s first — which featured a series of lectures on language in dozens of towns scattered across all 13 states. And in each state capital, Webster was lobbying legislators in an attempt to pass copyright law to protect his popular work from being pirated.

This feisty and often cantankerous New Englander had not thought much of his previous stops in Virginia. In his diary, Webster dubbed Petersburg “an unhealthy place.” However, his initial impression of Williamsburg was favorable. “This is the most beautiful city in Virginia,” he noted upon his arrival that afternoon.

Webster’s first order of business was to do a tally of all of Williamsburg’s residential real estate — something that the obsessive counter did on every stop of his tour.

“It consists of 230 houses well built and regular,” he observed. “The College of William & Mary is large and elegant.” Over the next few days, Webster enjoyed hobnobbing with distinguished members of William & Mary’s faculty such as the philosopher Robert Andrews (“a sensible polite man”) and the legal scholar George Wythe (“a good man”).

But Webster’s mood turned acerbic a few days later when only six people showed up for a lecture. “Several causes may be assigned for this inattention,” he mused. “The Virginians have little money & great pride, contempt of Northern men & great fondness for dissipated life.”

Disgusted, he returned to Richmond on Dec. 10. Though Webster lived almost another 60 years, he would never visit the South again.

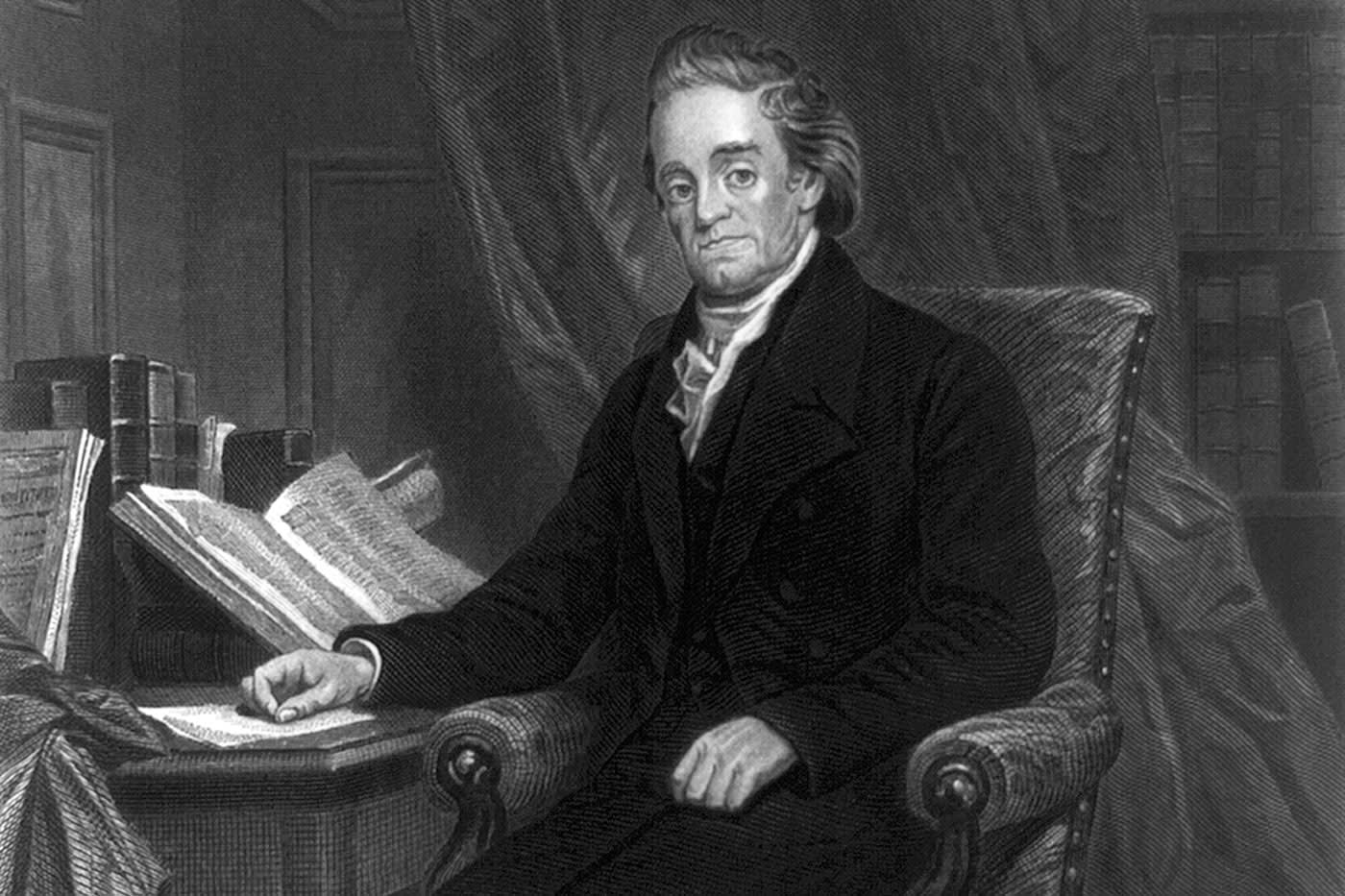

Whenever contemporary Americans think of Noah Webster — assuming that they are not confusing him with his distant cousin, Daniel Webster, the eloquent Massachusetts senator — they typically associate him with his legendary American Dictionary of the English Language, first published in 1828. But this massive reference work of some 70,000 definitions — the forerunner to today’s Webster’s Dictionary, which has been published by the Merriam-Webster company since 1847 — was actually his retirement project, which he started in 1798 at the age of 40.

By the time he threw himself headfirst into his eponymous dictionary, this hypomanic workaholic had already racked up a dazzling string of accomplishments. In fact, between 1783, when he first published the speller, and 1793, when he founded New York City’s first daily newspaper, Noah Webster nearly single-handedly defined America as a cultural and political entity. During this miraculous decade, he played a pivotal role not only in building from scratch the infrastructure of the new nation’s publishing business but also in both the drafting and the passing of the U.S. Constitution.

The one-man demographic machine also passed on all his data on the number of houses and of people in America’s cities to federal authorities who, in turn, folded this information into the 1790 census. And in a series of brilliant policy essays, Webster fleshed out nuanced positions on a host of topics from abolition to yellow fever.

As the eminent historian and former Yale president Howard Lamar has noted, even if we put aside his seminal contributions to English lexicography, Webster was actually “a multiple founding father.”

Webster’s speller was the first of the three volumes contained in his Grammatical Institute of the English Language, which also included a grammar published in 1784 and a reader published the following year. But the so-called “blue-backed speller” — it was covered in blue paper — was the book that turned Webster into an instant national icon.

As a schoolteacher, Webster had used the popular speller by the British scholar Thomas Dilworth, which had originally been published in 1740. But Webster grew increasingly dissatisfied with it. His main criticism was that Dilworth had failed to tailor his book to its readers — school-age children. For example, Dilworth divided up words according to abstract principles borrowed from Latin grammar. Webster proposed a simpler strategy: “Let words be divided as they ought to be pronounced...and the smallest child cannot mistake a just pronunciation.”

As the War of Independence was winding down, what really galled Webster was that Dilworth’s speller included a dozen pages devoted to the spelling of English, Irish and Scottish towns. For the youth of a new nation needing to establish its own identity, Webster considered such British touches anathema. Webster substituted a list of all the states and principal towns of the new United States of America. His speller would highlight all things American, including a uniquely American way of pronouncing and using the English language.

“A spelling book,” he would later write, “does more to form the language of a nation than all other books.” These remarks proved prescient. By the time the book went out of print in the early 20th century, it had taught five generations of Americans how to read and had sold nearly 100 million copies.

Even though Webster permanently soured on the South soon after his Williamsburg sojourn, Southerners eventually became fond of his speller. Even more than his dictionary, it was the book that connected all Americans with one another. In 1858, on the 100th anniversary of Webster’s birth, Jefferson Davis, who would become the president of the Confederacy just three years later, noted, “We have a unity which no other people possess and we owe this unity above all to Noah Webster’s Yankee spelling book.”

During the Civil War, while Southerners strategized nonstop about how to defeat Yankees like Webster, they couldn’t stop using his book. In fact, Confederate publishers jumped at the chance to release their own versions of the speller, which were virtual reprints except for a few minor changes “to suit the present condition of affairs.” In a Websterian tweak, the book’s illustrative passages were altered so that the South’s schoolchildren could learn about their new country — the Confederate States of America. For example, in a sentence featuring the president, readers were informed that the leader’s term in office lasted six years — not four.

With the speller giving him a national platform, Webster decided to address what many Americans saw as a critical problem — the lack of a strong central government under the Articles of Confederation, which had been passed in 1781. In 1785, Webster wrote a pamphlet, Sketches of American Policy, in which he offered a series of solutions. According to his analysis, since each state retained veto power over any legislation, “our pretended union is but a name and our confederation, a cobweb.”

What Americans urgently needed, he argued, was to redefine themselves as Americans — rather than as denizens of one state or another. “We cannot and ought not wholly to divest ourselves of provincial views and attachments,” he wrote, “but we should subordinate them to the general interests of the continent.”

Webster’s central policy prescription involved creating a new national leader called a president. He thought the entire country should be run as rationally as states such as his native Connecticut. “The state elects a governor or supreme magistrate and cloaths him with the power of the whole state to enforce the laws,” he noted. “Thus the whole power of the state is brought to a single point — it is united in one person.”

Soon after the publication of his pamphlet, Webster devised a plan to turn his ideas into action. The 27-year-old decided to enlist the help of the new nation’s most powerful man — namely, George Washington, who had recently retired after completing his position as the commander of the Continental army. In May 1785 — six months before his visit to Williamsburg — Webster made his case to Washington directly during a dinner at Mount Vernon. Washington took a liking to the young man and he promised to ask his friend, the Virginia legislator James Madison, to study the pamphlet. Madison would, in turn, incorporate Webster’s recommendation about the president into Article II of the Constitution.

But Webster’s role in shaping the Constitution went beyond composing the influential Sketches of American Policy. In May 1787, soon after he was appointed the head of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Washington knocked on Webster’s hotel room door; that summer, Webster, while working as a journalist in Philadelphia, would serve as Washington’s unofficial policy adviser. He would also regularly fraternize with other “Convention Men” such as the Virginia delegates James Madison and John Marshall, the future chief justice of the United States.

In early October, just a couple of weeks after Benjamin Franklin presented the final version of the Constitution to the delegates, Webster barricaded himself in his hotel room for a couple of days in order to crank out another pamphlet, this one designed to influence the states to ratify the Constitution. Called An Examination of the Leading Principles of the New Federal Constitution Proposed by the Late Convention Held in Philadelphia, Webster’s essay was published that fall. The future lexicographer made a powerful argument in support of the clarity of America’s founding document. As Webster argued, “The bounds of jurisdiction between federal and respective state governments are marked with precision.”

While Webster’s tract lacked the theoretical sophistication of The Federalist Papers — the series of 85 newspaper articles co-written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison, which also began circulating that fall — it was influential at the time. As South Carolina’s David Ramsay, who had presided over the Second Continental Congress in 1786, wrote Webster that November about his “ingenious pamphlet”: “it is now in brisk circulation among my friends.... It will doubtless be of singular significance in recommending the adoption of the New Constitution.”

In the fall of 1787, at the suggestion of his friend Benjamin Franklin, Webster moved to New York City to start a new literary periodical that he called The American Magazine. Though the publication was influential, it went out of business after a year. Unable to find many writers eager to contribute, he had to scramble for copy. To fill up the 64 octavo pages every month, Webster, under pseudonyms, wrote numerous satiric pieces such as “The Art of Pushing into Business and Making Way in the World” (an 18th-century version of How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying). He also wrote an advice column that gave dating tips to shy and bookish young men like himself.

The following year, Webster returned to his native Hartford and vowed to earn a living as a lawyer. In an update to President George Washington, he wrote, “I have written much more than any other man of my age in favor of the revolution, my country, & at times my opinions have been very unpopular. I wish now to attend solely to my profession [law] & to be unknown in any other sphere of life.”

But the compulsive writer could not stop — he continued to churn out words, though he typically published them either anonymously or under pseudonyms. He chimed in with thoughtful essays on the pressing issues of the day, including trade, transportation, street paving, global warming, slavery — he was a fervent abolitionist — and disability insurance. And thanks to his lobbying efforts, in 1793, Hartford established the nation’s first social insurance system for the poor, sick and disabled.

But by then, as Webster wrote to a family member, he was “very unhappy” because he was still having a hard time supporting his wife and children.

Fortunately, Webster was soon plucked out of his doldrums when the president came calling. Edmond Genet, the French ambassador to the United States, was doing his best to drag America into another war with France, and Washington figured that his trusted protégé could help him make his case for neutrality. At the time, most newspapers were party organs, and Washington asked Webster to start a new Federalist paper.

On Dec. 9, 1793, Webster published the first issue of The American Minerva, New York City’s first daily newspaper — Alexander Hamilton’s New York Post would not begin its run until nearly a decade later. In an editor’s note, Webster wrote, “It is the singular felicity of the Americans and a circumstance that distinguishes this country from all others, that the means of information are accessible to all descriptions of people.”

Webster believed that the fate of the new nation’s democracy depended on an informed citizenry — which would render its decisions based on a thorough assessment of all the available facts. 1793 was the same year that yellow fever began infiltrating America’s major cities and Webster would use his perch as a newspaper editor to conduct a survey about its effects. A few years later, Webster would turn all this number-crunching into a massive treatise on the deadly disease, which has since been hailed as the foundation of modern public health research.

In 1798, buoyed by a steady stream of income both from his successful paper and his speller, whose sales were starting to skyrocket, Webster moved back to New Haven. He settled into a commodious mansion once owned by the notorious traitor Benedict Arnold — Webster managed to snag the waterfront property for the bargain basement price of $2,666 — and resumed what he called his “literary pursuits.” In 1806, he published A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language — a concise version of his 1828 magnum opus, which contained brief definitions of 40,000 words.

He would continue to define words for the rest of his life. In fact, at the age of 81, he published a second edition of his massive dictionary. But while precise definitions are what Webster is best known for today, his legacy goes far beyond what he unabashedly called his “great book.” Webster also helped to define the new nation as a whole and, in so doing, continues to unite Americans from all regions — North, South, East and West — and from all walks of life with one another.

Joshua Kendall is a freelance journalist and the author of several books, including The Forgotten Founding Father: Noah Webster’s Obsession and the Creation of an American Culture. His most recent book is First Dads: Parenting and Politics from George Washington to Barack Obama.