Throughout October 1755, Williamsburg played host to Microcosm — “the most instructive as well as entertaining Piece [of art] now extant.”

Also known as the World in Miniature, this astronomical clock stood 10 feet high and 6 feet wide. It used more than 1,200 moving wheels and pinions as it played music and depicted scenes that ranged from the nine muses of Parnassus to a busy carpenter’s yard. This “elaborate and celebrated” mechanism, as it was described in the Virginia Gazette, was exhibited for a price “at the late Play-House.”

And how could people see this marvel? By buying a ticket at the Raleigh Tavern.

The Raleigh and other Williamsburg taverns often served as community spaces, with one of their functions being a ticket outlet: tickets of all sorts — even lottery tickets — could be purchased there.

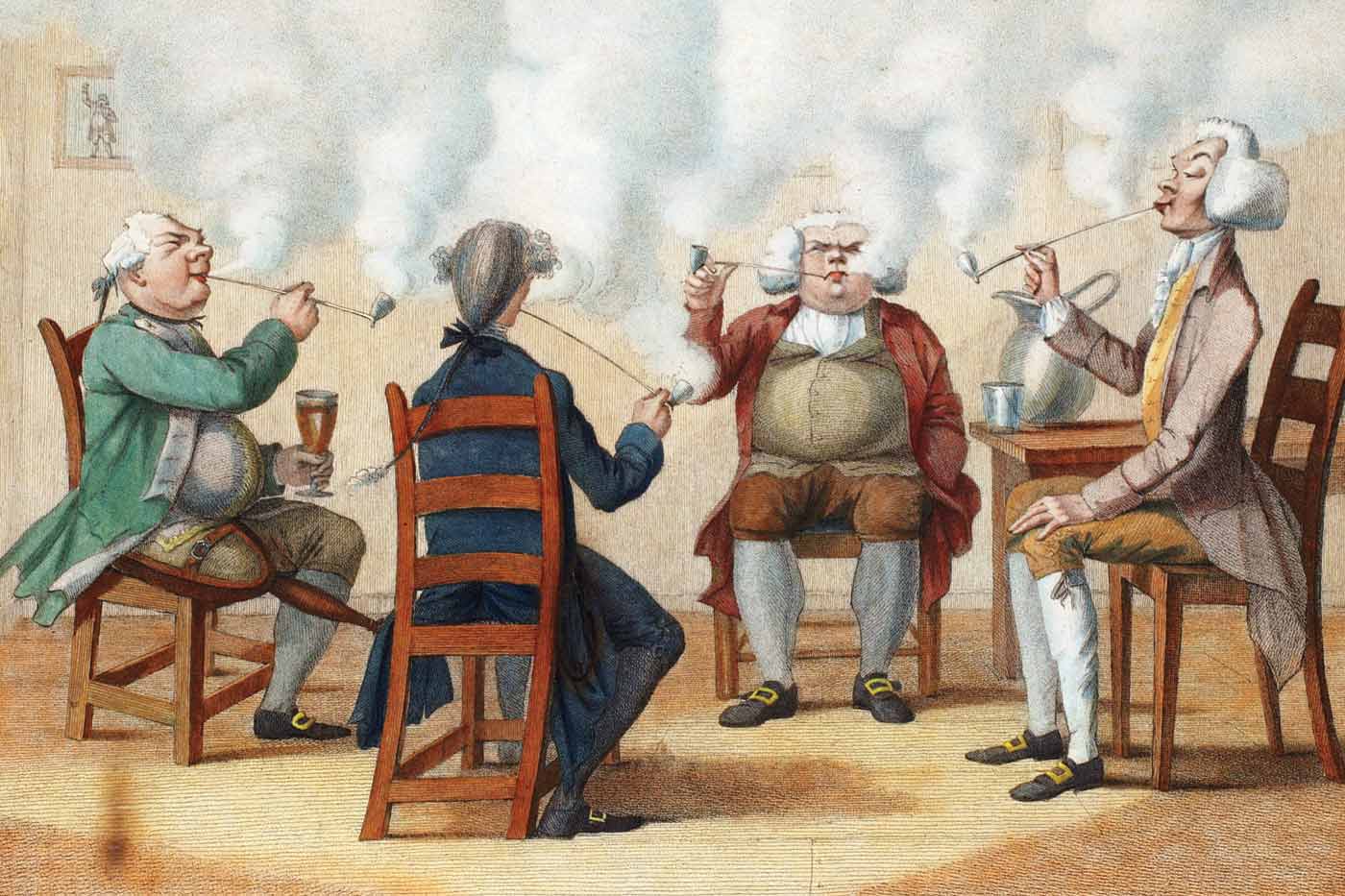

Licensed tavern keepers were bound by law to provide basic services to travelers, their servants and their horses. In 18th-century urban towns such as Williamsburg, taverns often exceeded this requirement, providing meeting spaces and a variety of amusements for locals and travelers alike. A tavern could be either an informal town hall or a beer hall. Tavern keepers sold merchandise, hosted cockfights and served private dinners. Patrons could also engage in games, attend social functions and, of course, drink alcohol. They could share a punch bowl and gamble on card games one night and attend a scientific lecture in the same building the next.

People of a variety of social classes could be found in taverns, though laws did prohibit enslaved individuals and apprentices from frequenting them, asserting that such amusements would detract from their work. However, enslaved people labored in the taverns, the enslaved people of white patrons did receive food and lodging, and both the enslaved and apprentices could occasionally be found socializing in a tavern.

The law also prohibited William & Mary students, though these laws were relaxed by the 1770s. The clientele was largely male, but some women could be found socializing and working there. Women did not travel as often as men, who made up the majority of farmers, planters and merchants passing through town for business, political or legal reasons.

Westward migration in the 18th century increased the demand for taverns, and more opened along popular travel routes to and from the most populous towns throughout Virginia and the East Coast. In the 1760s, Williamsburg boasted up to 21 taverns to serve a population of about 1,500, which swelled during Publick Times, when the court or the House of Burgesses was in session.

Though rural taverns often kept their services simple, urban taverns continuously added to their offerings to attract the increasingly diverse interests of their potential customers.

Spaces such as the Great Room at Wetherburn’s and the Raleigh Tavern’s Apollo Room, both mid-18th-century additions during a building boom in Williamsburg, offered tavern keepers the ability to host — and charge admission to — such special events as exhibitions, lectures, dances and large private dinners.

In November 1751, an elegant dinner in honor of the newly arrived Lt. Gov. Robert Dinwiddie took place in Wetherburn’s Great Room, where a few months later a series of subscription balls was held during a spring session of the House of Burgesses. Attendees paid half a pistole for admission to dance in the 25-foot-square room. Weekly balls were held in the Apollo Room during the same session.

Along with the high-minded lectures and elegant balls, taverns had plenty of potential for debauchery. Alcohol flowed throughout the night. A gentleman might enjoy a glass of wine to complement the calf’s head main course and then join his friends in consuming casks of ale.

Card tables and dice were staples at taverns, providing the materials for a night of gaming. Gambling took place on any given night, whether in card and dice games or a side wager on the next day’s horse race.

Sometimes patrons even based their wagers on drinking, occasionally betting on their ability to solve a puzzle jug. The game required participants to cover the correct holes and spouts in order to drink the jug’s contents without spilling.

These amusements were not universally accepted, as expressed in the Virginia Gazette in April 1751 by one clergyman who complained the establishments had strayed from their original societal purpose as “the Reception, Accommodation, and Refreshment of the weary and benighted Traveller.” He scolded that they had “become the common Receptacle, and Rendezvous of the very Dreggs of the People...where not only Time and Money are, vainly and unprofitably, squandered away, but (what is yet worse) where prohibited and unlawful Games, Sports and Pastimes are used, followed and practised, almost without any intermission.”

Yet among the “Dreggs” who patronized taverns were many members of the House of Burgesses who came to town for legislative sessions and who enjoyed the taverns socially and occasionally used the space for politics. When Lord Botetourt dissolved the General Assembly in May 1769 in response to its passage of the Virginia Resolves, burgesses gathered at the Raleigh Tavern as an alternative meeting place to the Capitol. Months before, the same venue hosted Lord Botetourt for a special reception upon his arrival in the colony.

In the weeks leading up to the General Assembly’s dissolution, George Washington’s account books show he bought subscriptions to three Williamsburg purse races as he enjoyed an evening in the Raleigh Tavern’s Daphne Room, where he also won 14 pounds, 17 shillings and sixpence at the card table. That night he slept in his room at Christiana Campbell’s Tavern, his preferred place to lodge while in Williamsburg.

Washington, like many people who spent time in Williamsburg, often visited various taverns in the evenings, as shown in his diaries and account books. He attended Ohio Company of Virginia meetings at Wetherburn’s Tavern, drew lotteries at Campbell’s, gambled at the Raleigh and ate hearty meals at all three — taking full advantage of the diversity of offerings provided.

Image: (Colonial Williamsburg Collections)

Take a tour of Wetherburn's Tavern to see the tavern amusements found there.