When Americans declared their independence from the British Crown, they spoke directly to the peoples of other lands. “Let Facts be submitted to a candid world,” the Declaration of Independence says, addressing itself to “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind.” A half-century later, just before his death on July 4, 1826, Thomas Jefferson cited the Declaration of Independence as being, to the world, “the Signal of arousing men to burst the chains . . . and to assume the blessings & security of self government.”

Indeed, the world was — and has been — watching. First France and then numerous other countries over more than 200 years have taken instruction, not merely from the fact of American independence, but from the ideas about governance that Americans were shaping in the founding era.

America’s Revolutionary era brought with it energy and exuberance that to this day we recognize as having put an enduring stamp on the history of constitutional ideas. Innovations abounded. Americans were devising ways to make constitutions superior to ordinary laws. James Madison, who feared placing power in the hands of only a few, argued for a larger republic. He and his colleagues believed in the notion of separation of powers, and introduced into the Constitution a system of checks and balances. American federalism offered another way of diffusing power in order to protect individual liberty.

France

Notions of liberty and equality were already widespread. In France, the American Revolution was seen as offering concrete hopes of making reality of those lofty ideas.

By 1777, Benjamin Franklin had arrived in France, nurturing the spread of American instruments of government, in particular the early American state constitutions and bills of rights. No document was more influential than the Virginia Declaration of Rights, agreed to in Williamsburg in 1776. The Marquis de Condorcet, a French philosopher who espoused the ideals of the Age of Enlightenment, declared that the Declaration’s author deserved “the eternal gratitude of mankind.” The Marquis de Lafayette, who distinguished himself on the American side at the battle of Yorktown, had a key role in drafting France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen in 1789. One only has to lay the French Declaration side by side with the Virginia document to see how much Virginia’s Declaration influenced the one drafted in France.

Soon the French national assembly turned to debating the contents of a new constitution. Moderates, such as Jean-Joseph Mounier, argued for a bicameral legislature and for a balance of power between the two branches of government. Advocates of this approach invoked American models, in particular the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780, whose chief architect was John Adams. More radical members of the assembly, led by the abbé Sieyès, argued for a unicameral, or single, legislature, the better to focus on the rising demands of ordinary people. The radicals liked Pennsylvania’s 1776 Constitution, the most democratic of the early American state constitutions — it provided for a unicameral legislature.

Even as ideas flowed back and forth between America and France, the two systems diverged. Bicameralism was rejected by the national assembly. Federalism was never seriously considered. While American courts were on the path to judges being able to strike down legislative acts as being unconstitutional, judges in France became seen as, in effect, civil servants. Their main mission was to see that the will of the people, as manifest in the national assembly, was enforced. In cultural terms, the Constitution of the United States was becoming a kind of ark of the covenant whereas in France it was the civil code, not the constitution, that was at the heart of national life.

Centuries have passed since the founding eras in America and France. Over those years, as nations, new and old, drafted constitutions, American ideas have helped frame the debate — sometimes out of admiration for the American experience, but sometimes the result of American enforcement.

Germany

In the European revolutions of 1848, the goals of reformers typically included democracy and constitutional government. Germans convened at Paulskirche in Frankfurt to draft a liberal constitution. Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America had already been translated into German. Tocqueville, a Frenchman who had traveled to the United States, had a lot to say about federalism and the judiciary in America, and his observations were widely quoted in the debates in Frankfurt. Carl Mittermaier, an eminent constitutional scholar at Heidelberg — and holder of an honorary degree from Harvard — extolled America’s “living Constitution.” He urged his colleagues “to turn to the experience of America.... Let us follow the American example, and we shall harvest the most splendid fruits.”

German conservatives, especially in Prussia, opposed the Paulskirche constitution, and it was never implemented. Yet the document became perhaps the most important legacy of 19th-century legal thought for the future of German constitutionalism. Many of America’s most basic constitutional ideas — constitutional supremacy, the rule of law, federalism — influenced the 1848 constitution. Those principles have their direct descendants in Germany’s Basic Law, adopted in 1949. The vibrancy of today’s German constitutional precedents, especially the decisions of its influential Constitutional Court, is a tribute to values shaped in good part in the forge of America’s constitutional workshop.

Philippines

Americans have sometimes consciously planted American constitutional ideas in other lands. After its victory in the Spanish-American War in 1898, the United States found itself in control of the Philippines. Anti-imperialists, William Jennings Bryan among them, argued that imposing an American-style government on another people was antithetical to American values.

Other leaders, however, saw commercial or strategic advantages in acquiring new territory. They augmented these practical considerations with an argument that Americans had a duty to bring civilization to the Philippines. Stirred by the spirit of manifest destiny, Sen. Albert Beveridge declared, “American law, American order, American civilization and the American flag will plant themselves on shores, hitherto bloody and benighted.” God, he said, “has marked us as His chosen people, henceforth to lead in the regeneration of the world.”

President William McKinley appointed William Howard Taft, who would become president in 1909, to head up the Philippine Commission. That body functioned as the Philippines’ legislature, pending the gradual emergence of an elected legislative body. The United States embarked on plans to Americanize the Philippines. That project had three main goals.

One goal was to establish a system of public education. American textbooks were used to promote values of hard work, honesty and independent thinking.

A second goal was to steer the Philippines, step by step, toward self-government. The first elections of the Philippine Assembly were held in 1907. The franchise was limited to adult males who were either literate or property owners. Even so, allowing the creation of native legislatures elected by the people was a novelty among colonial powers.

A third goal was the transfer of American law and jurisprudence. Law codes were revised to mirror American laws. American judges were imported to show Filipinos, as Taft put it, “what Anglo-Saxon justice means.” American case law became binding or persuasive in local courts.

Ultimately, in 1934, the process of drafting a constitution for the Philippines began. An act of Congress authorized the calling of a constitutional convention but provided that a new constitution must not only be approved in a referendum but also be approved by the U.S. president.

Delegates to the convention drew on a number of sources. The ultimate constitution, though not an exact copy of the U.S. Constitution, reflected strong American influence. Thus, it established a presidential system rather than a parliamentary one, which was common in many nations at that time. Eschewing parliamentary supremacy, the new constitution provided for constitutional supremacy and for judicial review of legislation.

The Treaty of Manila, signed by President Harry S. Truman in 1946, granted independence to the Philippines. The country’s government today is modeled after the United States, with power divided among three branches — executive, legislative and judicial.

Japan

The upheaval of war often brings constitutional change. The Potsdam Declaration of 1945 required Japan’s unconditional surrender and said that the Allies’ occupying forces would be withdrawn once democratic goals had been accomplished. Gen. Douglas MacArthur prodded the Japanese government to draft a new constitution to replace the old one, which had been based on Prussia’s 1885 constitution.

It became apparent, however, that the Japanese were inclined only to tinker with the existing charter. MacArthur worried that, if much time passed, Russia would want to have its say in the evolving regime. MacArthur put his military government team on the job, and, in a week’s time, it produced a draft. The Japanese government tried to resist but ultimately had to yield. The new constitution, largely a product of American hands, became effective in 1947.

When the occupation ended, one might imagine that Japan would lay aside the postwar constitution and write one for themselves. Yet, remarkably, not only is the 1947 constitution still in force, but it has never been amended. Despite frequent discussions, even the famous Article 9 — which renounces war — remains in place.

Europe, South America and More

Since the end of World War II, constitutionalism and democracy have been on the march in many places. In the 1970s, democracy came to Spain, Greece and Portugal. In the 1980s, authoritarian regimes were brought down in Argentina and Chile. Then, in 1989 came the most historic moment of all — the Berlin Wall came down, and the Soviet empire collapsed.

America’s Founders saw nationhood and constitutional government as irrevocably linked. In May 1776, the members of the convention meeting in Williamsburg instructed Virginia’s delegates in Philadelphia to introduce a resolution calling for American independence. On the same day, the convention set to work on a declaration of rights and a constitution for Virginia. The Virginia Declaration of Rights proclaims that the blessings of liberty can be secured only by a “frequent recurrence to fundamental principles.” That admonition is surely as apt for today as for the generation that gave it birth.

A.E. Dick Howard is the Warner-Booker Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Virginia. An expert in the fields of constitutional law, comparative constitutionalism and the U.S. Supreme Court, he was the executive director of the commission that wrote Virginia’s current constitution in 1971. He is the author of several books, including Constitution Making in Eastern Europe.

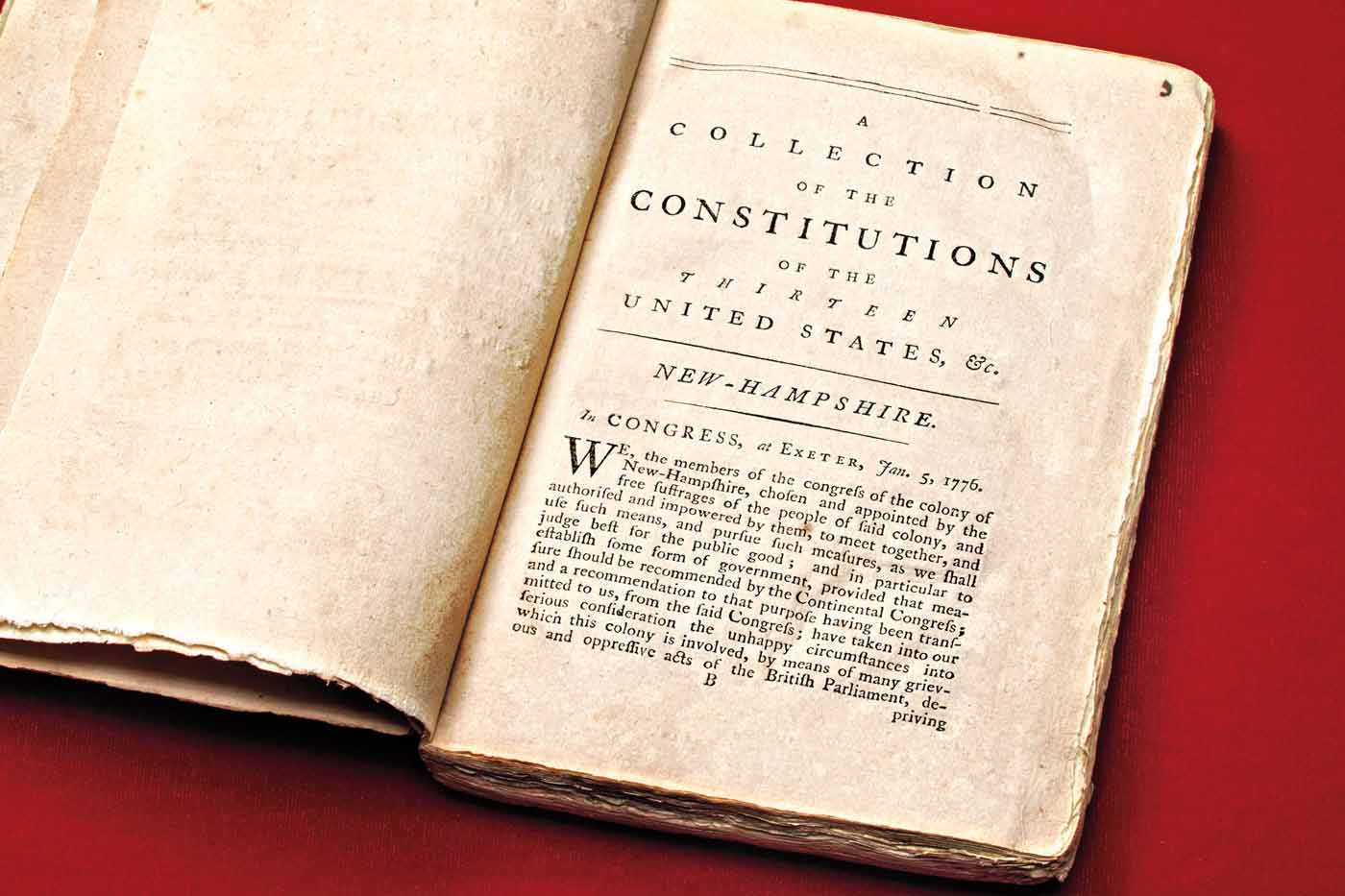

Image: A handbook, printed in 1781 by order of Congress before the Revolutionary War was even won, compiled key texts that were important in the establishment of the United States. It included, among other documents, the Articles of Confederation, the Declaration of Independence and 13 state constitutions. (Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library)