The faces on American currency haven't changed in 87 years. But sometime after 2020 — the year that marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment that gave women the right to vote — a portrait of a woman will join that of Alexander Hamilton on the $10 bill.

The debate over which woman rages on (as of this writing, at least). Picking the portrait that will grace the currency is important because the rendering becomes iconic. It's the image Americans see each time they make a cash purchase, and the face becomes emblematic of the leader.

Like, say, George Washington on the dollar bill. How much do we know about the most familiar image that appears on American money? And how is it, exactly, that Gilbert Stuart's portrait of our first President wound up on the dollar bill?

Stuart grew up in Rhode Island and moved to Scotland in 1771, when he was 16. Stuart's family was loyalist, but what led him to leave America was a keen desire to study art. Stuart established himself as a successful artist in London and then in Dublin. His daughter, Jane, in an 1877 story wrote, "He was completely absorbed with the idea of returning to America. To execute a portrait of Washington seems to have been his grand purpose."

Jane Stuart was not telling the full story, however. Stuart returned to America, at least in part, because he was deeply in debt. The artist Charles Robert Leslie recounted the following exchange: "Sir Thomas Lawrence said: 'I knew Stuart well; and I believe the real cause of him leaving England was his having become tired of the inside of some of our prisons. Well then, said Lord Holland, after all it was his love of freedom that took him to America.' " Stuart himself admitted that he hoped to "make a fortune by Washington alone" and that "if I should be fortunate, I will repay my English and Irish creditors."

In 1794 he arrived in Philadelphia, then the U.S. capital, and requested that the president sit for him. The sitting occurred in 1795. Stuart destroyed the first painting but made between 12 and 16 others. This likeness came to be known as the Vaughn portrait (since it was painted for the Philadelphia merchant John Vaughan, who sent it to his father, Samuel, in London).

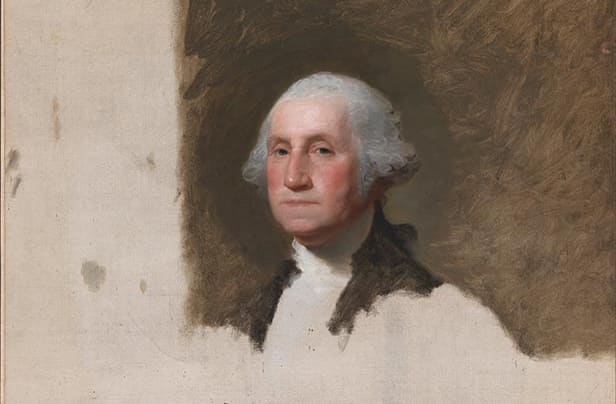

Martha Washington was sufficiently impressed by the portrait that she commissioned Stuart to paint a pair of portraits, one of her and one of her husband. George sat for this in 1796 in Germantown, just outside Philadelphia, and the result was the Athenaeum portrait (after the Boston library that later acquired it). It is the Athenaeum that appears on the dollar bill.

A third portrait from life, for which Washington also sat in 1796, became known as the Lansdowne since it was commissioned as a gift for the Marquis of Lansdowne.

The sittings did not go easily. Washington hated to sit for portraits; during a 1772 session with the painter Charles Willson Peale, he admitted he was in "so sullen a mood… that I fancy the skill of this gentleman's pencil will be put to it, in describing to the world what manner of man I am." Stuart was an expert in getting his subjects to talk, which animated their faces and helped him capture their personalities. But Washington, Stuart complained, perked up only when the conversation turned to horses or farming. Moreover, when Washington sat for the Athenaeum and Lansdowne portraits, he had a new set of false teeth that bothered him and distorted the shape of his face.

Though the Athenaeum portrait is the best known portrait of Washington — indeed, probably the best known portrait of anyone, ever — Stuart never finished it. Unlike the Vaughan bust and the full-length Lansdowne, the Athenaeum has only Washington's head and shoulders against a partly finished background. It's not certain why Stuart never finished the Athenaeum. One theory is that he didn't want to turn it over to Martha Washington and used its unfinished state as reason to hold onto it. That allowed Stuart to use the original to make copies, of which he made more than 70. These provided a major part of his income for years. Indeed, long before the Athenaeum landed on the dollar bill, Stuart referred to the painting as his "hundred-dollar-bill."

How good a likeness of Washington is the Athenaeum? Rembrandt Peale, an artist who admittedly was interested in promoting both his own portraits of Washington and those of his father, Charles Willson Peale, commended "the expression of the countenance" but noted that "the inaccuracy of its drawing and its deviation from the true style and character of [his] head will be evident on a comparison with [Jean-Antoine] Houdoni's bust." Stuart himself ranked the Athenaeum as second only to Houdoni's bust, which the French artist sculpted with the aid of a plaster life mask he'd make in 1785.

But Stuart clearly intended the Athenaeum to capture more than Washington's appearance. He wanted to show the man's character. "All his features," an acquaintance recalled Stuart as saying, "were indicative of the strongest and most ungovernable passions." Washington's reputation for "moderation and calmness" was, Stuart recognized, the result of "great self-command." With the nation's future still in doubt, Washington was the one man around whom all could rally, and Stuart's serene Washington provided just the right icon. Stuart's Washington, wrote critic John Neal in an 1823 novel, "was less what Washington was, than what he ought to have been."

The unfinished state of the painting may have added to its iconic stature. "His instinctive rightness of approach," wrote art historian Richard McLanathan," in showing just the head, without hands, setting, or accessory, is a major reason for its effectiveness. Nothing intrudes to vitiate the extraordinary controlled power and intensity of the image."

At this point, of course, Stuart's Washington is Washington, if only because of the ubiquity of dollar bills. The Athenaeum portrait appeared on numerous private bank notes throughout the first half of the 19th century and, as engraved by Alfred Sealey, on federally issued one-dollar notes starting in 1869. Stuart's portrait was also the source of a 1917 engraving by George E.C. Smillie. In Smillie's version, unlike in Sealey's version or Stuart's original, Washington is facing toward the right. Nonetheless, Smillie's version first appeared on the dollar in 1918 and remains there today. As early as 1823, Neal wrote: "If George Washington should appear on earth, just as he sat to Stuart, I am sure that he would be treated as an impostor, when compared with Stuart's likeness of him, unless he produced his credentials."

This story was adapted from an essay, "Dollar Bills" from a Colonial Williamsburg Foundation book called Why the Turkey Didn't Fly by Paul Aron. It is available at williamsburgmarketplace.com