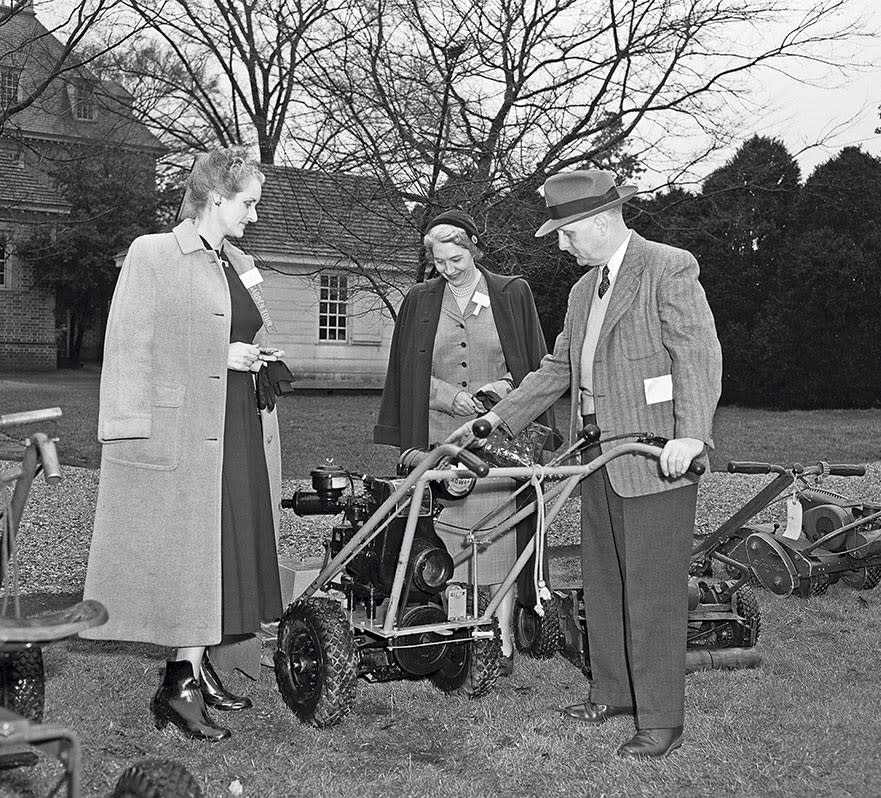

When it started in 1947, those who came to Colonial Williamsburg's symposium in search of garden knowledge weren't dressed to play in the dirt. Oftentimes, their gloves were white, their stylish hats didn't necessarily shield them from sun and their high-heeled shoes had to be protected from the mud and puddles that might be encountered during tours of Colonial Williamsburg's gardens.

The emphasis was more on history and less on hands-on applications. The subject matter at the first symposium centered, for example, on the Historic Area and how it was maintained, and participants spent five days covering the material. The attendees, mostly women invited from area garden clubs, assembled for lectures

at the Williamsburg Inn.

One of the oldest continuous garden symposiums in the country draws a very different crowd these days. Men and women come prepared to be comfortable, whether they're touring gardens, taking a bird walk or having breakfast with a gardener.

They come with questions about their gardens — about what they are and what they could be.

"It's certainly evolved," Laura Viancour said of the symposium. Viancour manages Colonial Williamsburg's landscape department and helps direct its programming. "They're getting away from elaborate landscape design. How can I be more earth-friendly?"

The 70th symposium — called Gardens We Call Home: Insights from the Trailblazers and Trendsetters — features lectures and workshops on ecological topics that include green gardening and water conservation. Other subjects include landscaping and choosing plants. And food.

"Food is very big, so tying the symposium into food is important," Viancour said. "There's been a generational change, really, where participants are more into DIY. Most of our audience already have gardens. They want to know how they can be more earth-friendly."

She remembers the words of garden expert and author P. Allen Smith, who spoke in Williamsburg in 2013 as part of the Foundation's speaker series. Members of the next generation, Smith said, are looking for what a garden can do for them.

"They want to know: 'Can I pick flowers? Can I grow vegetables?'" she recalled.

That's a long and winding path from the beginning. One of the first lectures was given by Arthur Shurcliff, who in 1947 was the landscape architect for Colonial Williamsburg. His topic: "How the Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg were Restored."

That and other lectures were listed in a program brochure titled: "Colonial Williamsburg Presents Its First Symposium on Eighteenth Century Flowers and Gardens."

By the third year, the event had become the Williamsburg Garden and Flower Symposium, and the following year, there was another new title — the Colonial House and Garden Symposium — and a new partnership with "House and Garden" magazine. Bolstering the inclusion of buildings prompted the addition of studies of small houses during the Colonial period, lectures on Colonial house design and stories of the restoration of both houses and gardens in the Historic Area.

By Year Five, the event was simply the Garden Symposium and two sessions were needed to accommodate those who wanted to attend. By then, new speakers joined those from the Foundation staff, including horticulturalists from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and presidents of national garden clubs and herb societies.

Flower arranging had become a regular part of the program by the 1950s. Cynthia Wescott, a plant pathologist and rose expert from Glen Ridge, N.J., and the author of a book called The Plant Doctor, told 1956 symposium attendees that they shouldn't be afraid to try to grow roses. According to the title of her talk, anyone can.

It also recognized that gardening also included the care of house plants and experts on azaleas, camellias and rhododendrons joined a growing crop of speakers.

The subject matter in the 1960s shifted to "Planning and Planting for Easy Maintenance." Topics could also be philosophical: Author Alice W. Burlingame discussed the therapeutic advantages of gardening. And food increasingly became part of the conversation. In 1963, Ruth Matson, author of Cooking by the Garden Calendar offered a talk on "Gardening for Gourmets." Her gardening career, she said, was "always in miniature. … A gardener with a vegetable patch."

"The best way to plan a garden, I find, is to settle comfortably into an arm chair and dream about food," she said.

As the symposium moved into its fourth and fifth decades, "green" became more and more an ecological term. Air pollution and its ramifications were discussed, as were the implications of the world's vanishing plants. By the 1990s, gardens were something to be experienced as in a 1993 program of "Cultivating the Senses — The Sights, Sounds and Aromas of the Garden."

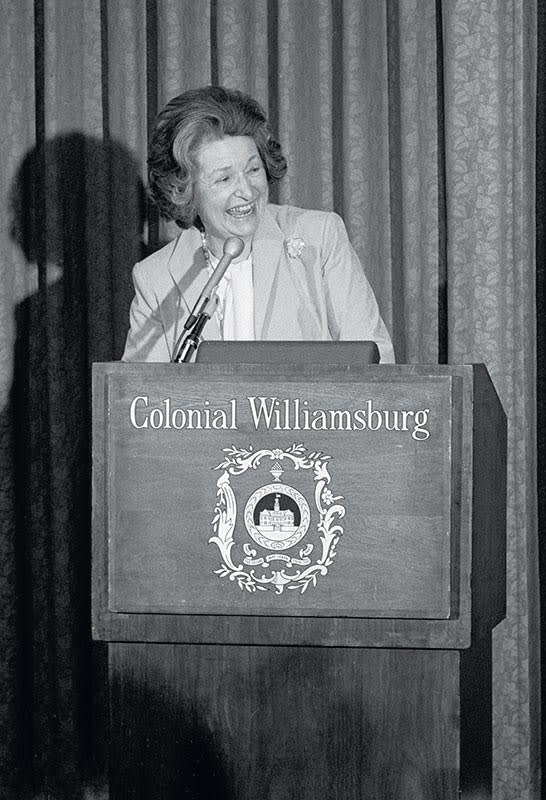

The symposium also began to attract nationally known garden evangelists. Lady Bird Johnson, who touted beautification projects during her time as first lady, spoke to symposium participants during a lunch of salmagundi salad and strawberry cream cake in 1984. By then, she had founded the Wildflower Research Center, which sought to teach the environmental necessity, economic value and natural beauty of native plants.

As the pastime became more popular, it became a more visible theme on television. Roger Swain, a longtime host of the Public Broadcasting System's "Victory Garden," tackled the topic of "Bugs, Birds and Beasties — Getting a Grip on

Wildlife in the Garden" in 1993. Joe Lamp'l, who is seen on another PBS program called "Growing a Greener World," is making a return appearance this year at the symposium.

Television and the Internet spurred changes in the way the symposium is planned, Viancour said. "You don't have to actually go somewhere to learn something," she said. The easy availability of information makes the choice of subject matter all the more important.

"In the end, it's about making it your own," Viancour said of gardens. "It's your space and you need to enjoy it. I think that's what these speakers are about — making it your own."