The nameless infant sleeps innocently, pudgy arms folded, cheeks aglow, head tilted and betraying the barest trace of a grin. There's a power that transcends the portrait's rustic artistry, something elegant and telling in its simplicity, an aura that evokes viewers' nostalgia and, in many cases, captures their hearts.

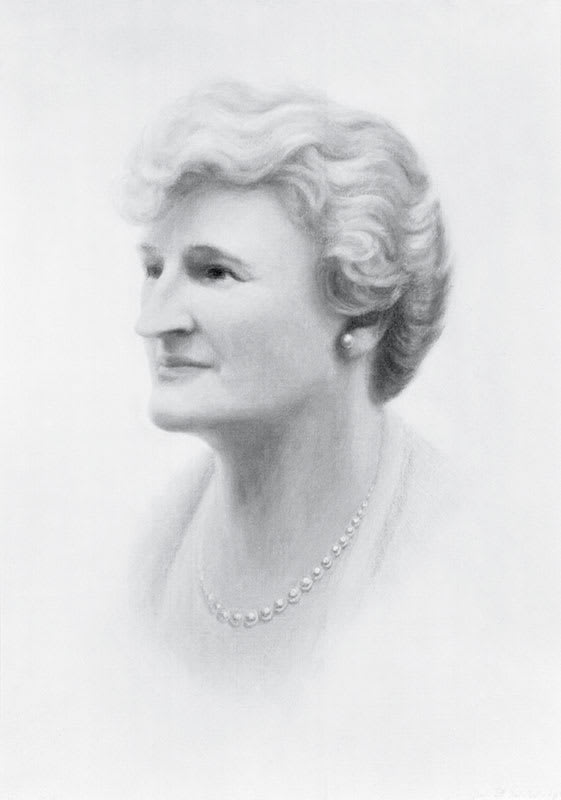

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller was among those enamored of the portrait. Baby in a Red Chair was one of her first acquisitions when she began collecting folk art in 1929. Little could she have known then that so many others would share her fondness for these creations at what has become the world's oldest continuously operating museum devoted to the collection and study of American folk art.

This year, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum celebrates its 60th anniversary. Some 420 works from Mrs. Rockefeller's original collection became a permanent part of Colonial Williamsburg in 1957, a way for her husband, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., to honor his late wife's fondness for folk art.

Since then, Colonial Williamsburg has carried Abby Rockefeller's mantle by expanding her collection — which included paintings, drawings and sculpture — to more than 7,000 objects. This broad body of American material culture — furniture, needlework, pottery and metalwork, among others — was all created by people who rarely had academic artistic training. The people who created these articles and the time and place in which they existed tell America's story.

In the early 20th century, few other aficionados shared Abby Rockefeller's appreciation of the work of folk artists. Elite art collectors and members of high society at that time maligned what they considered to be untrained and sophomoric attempts at creative expression. Many in the art community used subtly derogatory terms to swipe at folk art, often referring to it as "provincial" or "outside" art.

But Abby Rockefeller bucked conventional wisdom, finding in folk art the abstract perspectives that were accepted in modern art. Her financial resources, broad knowledge of the arts and friendship with folk-art dealers and scholars offered her the opportunity to acquire significant objects, said Laura Pass Barry, Colonial Williamsburg's Juli Grainger Curator of Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture.

That pioneering spirit is celebrated in America's Folk Art, an exhibition that opens in July. It celebrates the museum's milestone anniversary while also paying tribute to Abby Aldrich Rockefeller.

The recently opened portrait exhibition We the People: American Folk Art Portraits provides a glimpse of the value Abby Rockefeller and other early collectors saw in folk art. Though the artists were largely unknown and specific attributes seem simplistic, the portraits offer historical revelations and artistry.

Like Baby in a Red Chair, a portrait Abby Rockefeller collected early on is Child in Yellow Dress with Grey Cat. Little is known about the subject or the artist. No art expert is needed to spot the details that wouldn't have been present in work by a classically trained artist. The proportions are a bit off — the girl's shoulders are too flat, for instance, and the cat's tail is too long. Yet style and technique shape the flowers on the girl's dress and convey the cat's sharp teeth.

Abby Rockefeller had a discerning eye that shaped a world-class collection. These objects are notable examples of their kind and continue to draw viewers in today, Barry said.

"Mrs. Rockefeller especially liked the aesthetic appeal of folk paintings," she said. Her son Winthrop recalls that his mother gave private names to some of the portraits that especially resonated with her.

But the sight of the portraits was just one part of a greater importance that folk-art enthusiasts like Abby Rockefeller took from these homespun objects. Beneath the paintings and sculptures were larger truths about what was happening in the evolving American Nation at the time artists created them.

For example, in 1973 Colonial Williamsburg acquired the portrait of Eleazer Bullard, one of four members of the Bullard family painted by Erastus Salisbury Field in the 1830s. While the subjects and artist may not be well remembered, portraits speak of a growing middle class in American society after the Revolutionary War.

It's known, for instance, that Field painted portraits like these in a single day for $4. "Here you have an art form that everyone was a part of, both the patrons and the artists," Barry said. Though the portraits likely hung proudly for many years after the artists created them, their work was, in essence, a financial transaction. As the middle class expanded, more Americans had the wherewithal to commission portraits — family keepsakes in those pre-photography days. And a growing number of amateur artists stepped in to fill that need in their community.

So when Colonial Williamsburg adds to its collection of folk art, it's not merely saving the likeness of a single American or a family from the past. Rather, the art documents a tapestry of American history, including day-to-day interactions that define a time and place.

In 2004, for example, Colonial Williamsburg acquired a portrait of sisters Sarah Bell and Annie "Fannie" Russell, thanks to funding from Tim Caviness Jr. and his wife, Linda. It is one of only a dozen known portraits by 19th-century artist and Civil War veteran William Anderson Roberts, though he is believed to have painted more than 200 portraits. It is also the first painting acquisition from North Carolina for the collection. But countless other stories lie in that conserved portrait, waiting to be revealed. Shelley Svoboda, a senior conservator of paintings for the Foundation, worked to ready the portrait to be part of the permanent collections.

"We were fortunate in this case to have a painting that was, for the most part, unchanged from what the artist made," Svoboda said. "It's rare that things come to us like this. A stretched canvas is vulnerable, and it is not too easy to find a piece that's made it through time without having encountered past damage."

Nevertheless, Svoboda worked for about three weeks using techniques that could later be reversed by conservators, if need be. Svoboda added a passive insert to add appropriate support. This remains invisible to the viewer and is easily reversed. She also consolidated some layers of paint that were not stable.

The work was a small investment for an invaluable return. "This portrait offers a really rich body of information," Svoboda said. "It's a primary document for us to use as a springboard for understanding the past."

The $40 million campaign to expand the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum recently concluded, and ground for the new wing will be broken in April. The first large-scale expansion of The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg will create a fitting home for the collected artistic and cultural treasures. Some offer glimpses of the 18th-century stories told in the Historic Area, including the post-Revolutionary days, giving us a record of Americans navigating the novel idea of self-government.

But all of the pieces, from whatever artist in whatever era, tell us something about ourselves as Americans. The folk art represents the vision of Abby Rockefeller, who saw this Nation as an entity where everyone has something to contribute.

So this anniversary is an occasion to look to the future as much as the past, as current opportunities to expand gallery space and add to the folk art collection will help preserve this special part of history in perpetuity. That commitment to the past, present and future mirrors Abby Rockefeller's devotion to a storytelling art form.