Writing from London in October 1766, Benjamin Franklin complained that George Grenville was still “besotted with his Stamp Scheme.” This despite the violent rebellion the Stamp Act of 1765 incited in America. And George III dismissing Prime Minister Grenville a few months after its passage. And Parliament repealing the controversial tax in March.

Britain wanted the colonies to pay for the defense of North America, and Franklin thought a colonial post office was a more profitable way to achieve that, but Grenville never lost faith in what gossipy Horace Walpole called “his darling Stamp Act” — despite the defects that Americans discovered and exploited.

Faced with an unprecedented wartime debt when he took office after the French and Indian War, Grenville tightened enforcement of the Navigation Acts and had Parliament revise the customs duties on sugar and linens. When, in March 1764, he announced a plan for stamp taxes in the colonies, more than revenue was at stake. Grenville aimed to consolidate Parliament’s control over the American colonies and the rest of Britain’s sprawling empire.

George III had spoken occasionally in private about taxing the colonies since taking the throne in 1760, but it was Grenville who focused on stamps rather than other revenue measures. English consumers had been familiar with tax stamps since the 1690s. British legislators felt so familiar with tax stamps that Grenville and his aides felt little need to explain them to anyone, or to devote much effort to the drafting of legislation. They felt that everyone knew the stamp laws and the American tax would be formed on the same plan.

In the spring of 1764, the agents who lobbied for the colonies in London asked to see the text of his intended stamp-duty legislation. Grenville declined because, according to one of the agents, “the Bill was not yet thoroughly digested.” Although not an outright lie, the response was misleading as his Treasury officials had been working on preliminary drafts for two years. Final provisions of the Stamp Act would not be decided until months after Grenville met with the colonial agents, who saw those details only when the act was introduced in the House of Commons in January 1765. No American, including governors and crown officials, saw the Stamp Act before its publication in newspapers after its passage.

Throughout their preparation for the Stamp Act, Grenville and his aides thought they knew far more than they did — and their lack of knowledge led Great Britain into a catastrophe. Three attractive features blinded them to the unforeseen vulnerabilities of stamp taxes.

First and foremost, stamps were taxes. Their purpose could not be mistaken. Stamp duties were designed to collect money. Although Grenville cared about increasing American revenues from customs duties on sugar, molasses and linens, he valued stamp duties precisely because they were not meant to regulate imperial trade or influence consumer behavior (aside from making dice, playing cards, newspapers and litigation slightly more expensive). In public debate, Grenville vehemently disagreed with Americans who distinguished regulatory duties from internal taxes, or legislation from taxation, but privately he and his aides regarded their Stamp Act as “a great measure on account of the important point it establishes, the right of Parliament to lay an internal tax upon the Colonies.” Imposing stamp taxes in America, they privately said, would enforce Parliament’s claims of absolute authority over the colonies and empire.

Second, Grenville believed that stamps were the most efficient way to tax America. As he often reminded Parliament, a stamp tax “in a great degree executes itself” because documents “not stamped are null and void.” Based on English experience, his logic was plausible. Suppose Mr. and Mrs. Jones wanted to buy a house. If the validity of their deed demanded a tax stamp, they might grumble about its cost but would pay for the stamp to make sure their deed held up in court. Eighteenth-century English consumers accepted stamp duties for discretionary purchases such as newspapers, dice and playing cards just as Americans today pay little attention to tax stamps on liquor, cigarettes and hunting licenses. Individual resistance was self-defeating. Aside from forgeries, which were unlikely and infrequent, the only thing that could wreck a stamp tax was organized and unanimous defiance by an entire population. That prospect had never crossed Grenville’s mind — until it happened.

Third, Grenville believed that his plan would be cheap to administer. A stamp tax, he assured Parliament, “requires few officers and even collects itself.” The anticipated costs at the Stamp Office in London were only modest salary increases for a few senior officials, additional warehouse space, two new clerks and a porter. Stamp officers in America would pay themselves and any deputies out of an 8% commission on the taxes they collected.

Despite British confidence in stamp duties, Americans discovered and exploited inherent weaknesses that Grenville did not anticipate. They also exploited his first tactical error, announcing the Stamp Act in March 1764 but postponing its drafting and enactment until 1765. Claiming that he needed time to identify all the American legal documents for which stamps might be required, Grenville got Parliament to assert “it may be proper to charge certain Stamp Duties in the said Colonies and Plantations” — a resolution he portrayed as an endorsement of “the power and sovereignty of Parliament, over every part of the British dominions, for the purpose of raising or collecting any tax,” in the words of a Virginia agent.

Grenville said nothing in public about using the Stamp Act to create a precedent for taxing America, but colonial lawyers and legislators were as obsessed as their British brethren with avoiding dangerous precedents and creating advantageous ones. According to Britain’s preeminent authority, Sir William Blackstone, precedent itself was “the first ground and chief corner-stone” of the common law and of Britain’s celebrated unwritten constitution. The very earliest public comment about Grenville’s announcement — a letter reprinted in New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Providence in April and May 1764 — warned that the proposed stamp tax “would be small and...therefore in itself not an object for opposition; but should this internal tax be effected, it might in any future times be a dangerous precedent in the hands of a bad ministry.”

The Stamp Act terrified Americans. It was a slippery slope toward catastrophe.

“If the British Parliament have a Right to impose a Stamp Tax,” one New Yorker snarled, “they have a Right to lay on us a Poll Tax, a Land Tax, a Malt Tax, a Cider Tax, a Window Tax, a Smoke Tax, and why not tax us for the light of the Sun, the Air we breathe, and the Ground we are buried in?”

Massachusetts leaders also called it a “Dangerous precedent.” Georgia legislators complained that “the manner of imposing [stamp duties] greatly alarms us, as we know not where the precedent may end.” Virginians declared that “Every Mention of the parliament’s Intention to lay an Inland Duty upon us gives us fresh Apprehension of the fatal Consequences that may arise to Posterity from such a precedent” — “not only we & our Children, but our latest Posterity may & will probably be involved in its fatal Consequences.”

Although Grenville successfully evaded a serious debate in Parliament, his announcement ignited a firestorm in the American colonies. Aside from customs and import duties, Americans had no direct experience with any kind of parliamentary taxation within their communities. The risk of admitting Parliament’s nose into America’s tent was dire.

“They who are taxed at pleasure by others, cannot possibly have any property,” warned a Rhode Island pamphleteer, and “they who have no property, can have no freedom, but are indeed reduced to the most abject slavery.” Defeating the dangerous precedent of Grenville’s Stamp Act was the only way Americans could defend their liberties and property.

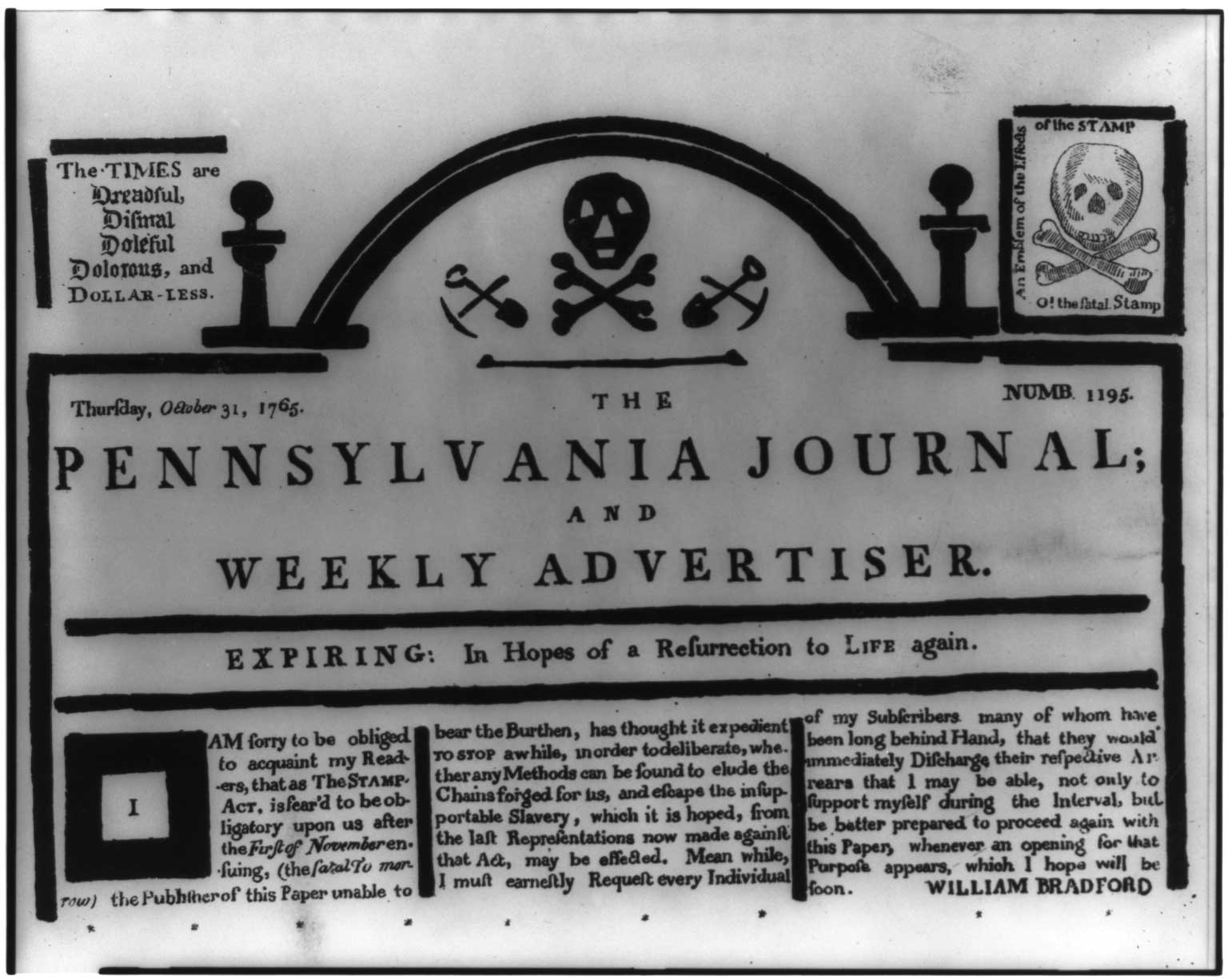

During the autumn and winter of 1764, the postponement of the act gave Americans time to explain their constitutional objections to parliamentary taxation and to organize intercolonial opposition to such a dangerous precedent. By the time the Stamp Act reached North America in the spring of 1765, the colonies from Georgia to Massachusetts had agreed on the constitutional principles of their opposition. Once they confronted the specific provisions that were scheduled to take effect on Nov. 1, 1765 — duties on 55 kinds of legal documents, pamphlets, newspapers and every individual advertisement in every gazette — they were ripe for rebellion.

The new tax fell heavily on lawyers and printers, professions that savvy politicians try not to alienate. Lawyers and courts would need stamps for legal documents, and printers, instead of relying on local paper mills, would be required to purchase prestamped paper manufactured in England, transported to America and sold by stamp officials.

Worse still, in an agricultural society utterly dependent on credit transactions and chronically devoid of circulating coin or currency, the Stamp Act required payment in sterling. “It might as well have ordained, that every man in the colonies should be seven foot high,” one London merchant remarked, “since they are both equally impossible.”

Grenville’s scheme to seize “the little silver and gold we have,” a crown official reported from New York, “has lost Great Britain the Affection of all her Colonies.”

Because everybody groused about taxes, Grenville and his aides initially regarded American protests as merely an acknowledgment that they could not escape paying stamp duties. In fact, protests marked the beginning of intercolonial defiance by an increasingly united population. American resistance targeted two especially vulnerable aspects of Grenville’s program — the transatlantic logistics of implementing the Stamp Act and a potentially devastating interruption of Anglo-American commerce.

Grenville sought to win support for the new duties by appointing native-born stamp officers in each colony from “the most respectable people in their several provinces”: Ben Franklin’s friend John Hughes in Pennsylvania. Andrew Oliver in Massachusetts. Jared Ingersoll in Connecticut. Augustus Johnson in Rhode Island. George Mercer in Virginia. James McEvers in New York. Zachariah Hood in Maryland. The list went on for all 26 North American and Caribbean colonies — supplying American activists with a convenient roll call of the “enemies of their country.” During the year after angry Bostonians destroyed stamp officer Andrew Oliver’s house in August 1765, a total of 60 riots sent an intimidating message to stamp officers and errant merchants. By Nov. 1, when the Stamp Act took effect, all Grenville’s respectable appointees had been forced to resign and, in some places, flee for their lives.

Americans also fought the Stamp Act at the docks. From Savannah to Boston, British officials scrambled to prevent the capture and destruction of stamps and stamped paper by hiding them aboard Royal Navy vessels or in harbor strongholds such as Fort George in Manhattan and Castle William in Boston. Ignorant of the day-to-day workings of the Stamp Office in England, Grenville had given no thought to the staggering logistical task of delivering and distributing tax stamps and stamped newsprint in the colonies. The first shipment for Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island weighed 12 tons!

Smaller than most modern commemorative postage stamps, Grenville’s American tax stamps were issued in denominations ranging from half a penny to 10 pounds sterling. Among the most consequential was the 4-penny tax stamp intended for every routine bill of lading used in transatlantic commerce. According to the law, ships and cargoes sent forth without properly stamped documentation after the Stamp Act took effect risked capture and confiscation by customs officials and the Royal Navy. If Americans could successfully prevent the use of tax stamps on commercial documents, strict British enforcement of the Stamp Act would effectively close down all Anglo-American trade — commerce that had grown to comprise about 40% of the overall economy of Great Britain.

An internal report from Grenville’s own Treasury Department had warned him that Americans were likely to regard the Stamp Act as a “Matter of real Terror and Punishment.” Americans turned the table on Grenville by defying the Stamp Act, reducing their exports and refusing to import British manufactured goods. Resistance to the Stamp Act taught Americans how to employ punishing economic sanctions against Great British. The nonimportation agreement signed by New York merchants in October 1765 — refusing to accept delivery of “Goods or Merchandize, of any Nature, Kind or Quality whatsoever, usually imported from Great-Britain...unless the Stamp Act be repealed” — was typical.

Decades before Irish protestors coined the word “boycott” in the 1880s, American communities used nonimportation agreements, supported by local committees and enforced by local militia who called themselves Sons of Liberty, to fight the Stamp Act, with devastating effect. Although British leaders remained hostile toward American protests, Parliament eventually yielded to a petition campaign organized by British manufacturers on behalf of tens of thousands of artisans and laborers thrown out of work by the closing of the American market. British merchants in London, Bristol, Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester and other manufacturing towns feared bankruptcy if the collapse of American trade prevented them from routinely collecting payments on American accounts valued at 4,450,000 pounds.

While Parliament pretended that its deliberations were unaffected by colonial resistance, its committees heard damning testimony from businessmen, merchants and artisans whose incomes depended on American commerce. The plight of these suffering Britons offered Grenville’s successor, Charles Watson-Wentworth, the Marquess of Rockingham, face-saving grounds for repealing the Stamp Act in March 1766. Stung by the colonies’ perceived insolence, Parliament linked the repeal to a Declaratory Act asserting Britain’s authority to impose laws and taxes on America “in all Cases whatsoever.”

Thomas Hutchinson, lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, had tried to warn Parliament against the Stamp Act. “You will,” he accurately predicted, “lose more than you will gain.” The revenue collected from the American Stamp Act totaled only 4,000 pounds — far short of Grenville’s original estimates and well below the expenses incurred for its unsuccessful implementation. The political consequences of Grenville’s “darling Stamp Act” were incalculable.

Grenville’s attempt to trick the Americans into accepting stamp duties as a precedent for parliamentary taxation aroused fatal distrust of British intentions. His suppression of colonial petitions impeded honest transatlantic debate about imperial governance and foreclosed any prospect of successful negotiation or compromise. His administration encouraged claims of authoritarian supremacy over the colonial populations of North America, India and the Caribbean. Yet his infatuation with stamps as a tax that “requires few officers and even collects itself” gave Americans unforeseen opportunities to formulate tactics of resistance and rebellion.

George Grenville died in 1770. He was not solely responsible for the American Revolution. Yet there is truth to the charge, voiced against him during parliamentary debates over the repeal of the Stamp Act, that he was “the author of all the troubles in America.”

Jon Kukla is a historian whose books include Patrick Henry: Champion of Liberty. He lives in Richmond, Virginia, where he is currently writing Rehearsal for Revolution: The Stamp Act Rebellion, 1764–1766.