National leaders cringed when he made outrageous statements. He took advantage of prejudices. Supporters applauded his plain speaking. Truth was less important than impact and he had no compunction about telling an outright lie if it served his political purpose.

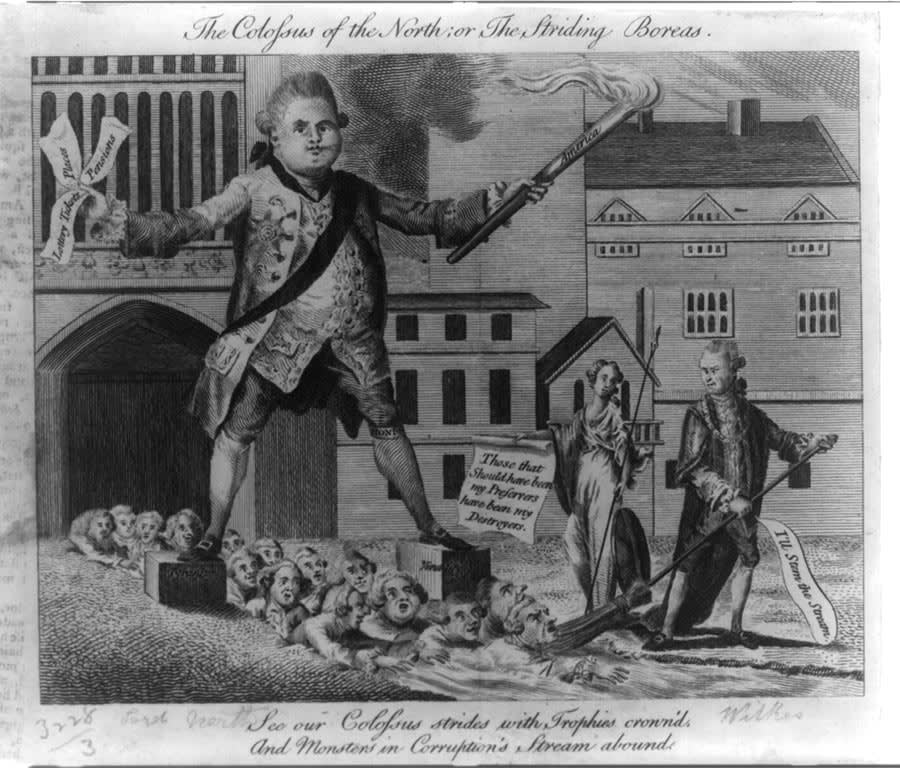

A self-promoter who mastered the media, John Wilkes rode a wave of popular renown. His message was laced with the salacious. He eviscerated critics. He advocated nationalism and nativism, warning that ethnic groups were invading and destroying the country. Though not a handsome man — some, in fact, called him the ugliest man in England — he built a reputation as a rake and womanizer. The people loved him for his outrageous antics, embraced his demagoguery and thrust him onto an international stage as the symbol of English liberty.

Though an ocean away, Colonists celebrated the Englishman as a champion of the same freedoms they sought. Wilkes advocated the right of the voters to determine their representatives and hailed those representatives as the true protectors of English liberty. He stood against the arbitrary power of the ruling class and railed against the corruption of government, even when his attacks led to his arrest and imprisonment.

Wilkes was elected to the House of Commons in 1757 and though there was nothing in the first couple years of his public life that foreshadowed a meteoric rise to fame, he did possess the wit, presence and an ambition that helped make him a popular hero.

By the middle of the 18th century, Whig politics dominated Britain. Whigs were anti-Catholic. They advocated the supremacy of Parliament and were ardent supporters of "An Act Declaring the Rights and Liberties of the Subject and Settling the Succession of the Crown" passed by that body in 1689 and more commonly known simply as the 1689 Bill of Rights. Whigs believed in a limited constitutional monarch. They grew out of the English Revolution, were shaped by a rising middle class and were fueled by the power of British mercantile trade.

John Wilkes was a staunch Whig.

A War of Words

George III ascended to the throne in 1760, just as the fortunes of war were shifting in favor of Great Britain. In 1762, George III appointed as prime minister of Great Britain his former tutor, Scottish nobleman John Stuart, Lord Bute. It was Bute who was responsible in 1763 for negotiating the peace in the Seven Years' War, known in America as the French and Indian War. Critics, including Wilkes, charged that Bute conceded too much to the vanquished French and Spanish.

When Bute established a pro-government newspaper called The Briton, Wilkes — with poet and playwright Charles Churchill — began publication of The North Briton. "North Briton" referred to Scotland and was a clear reference to Bute. It was not a compliment. "The principal part of the Scottish nobility are tyrants and the whole of the common people are slaves," Wilkes declared. Historian Linda Colley in her book, Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707-1837, calls it "Scottophobia." Scots were, in Wilkes' eyes, aliens who could never become integrated with true Englishmen.

The year 1745 — still fresh in English memory — gave Wilkes additional ammunition for his published assaults. That was the year that Charles Edward Stuart — known as Bonnie Prince Charlie — led the Highland clans in a rebellion designed to overthrow the Hanoverian, King George II, and return the Stuart line to the thrones of Scotland and England. The rebels were known as Jacobites. The North Briton attacked Bute as a Jacobite — traitor to the throne — and accused him of having an affair with the queen mother. The newspaper was an instant sensation — circulation skyrocketed. Bute became a national villain and was forced to resign as prime minister.

The resignation did not stop Wilkes' attacks on the government. In an infamous issue of The North Briton — No. 45 — Wilkes asserted that the insidious Jacobite influence over the government continued. Jacobites, Wilkes said, were intent on destroying English liberty and enslaving the people of Britain. He attacked King George III's speech before Parliament. Criticizing the king directly could lead to a charge of seditious libel and so Wilkes tried shifting the focus to the recently resigned Lord Bute by saying, "The King's Speech has always been considered by the legislature, and by the public at large, as the Speech of the Minister." The king's address lauded the peace settlement of 1763 as an accomplishment. For Wilkes, it was a travesty. "What a shame was it to see the security of this country … sacrificed."

And who was to blame? Wilkes implied it was Bute and the Jacobites influence in government. Then he went on to say, "The King of England is ... invested by law with the whole executive power. He is, however, responsible to his people for the due execution of the royal functions, in the choice of ministers, &c. equally with the meanest of his subjects in his particular duty."

George was furious. The government issued general warrants to arrest those involved in the publication of The North Briton on charges of seditious libel. General warrants gave officers of the king broad discretionary power to seize property and arrest individuals. Also called "writs of assistance," the general warrants represented the kind of arbitrary power that ardent Whigs deplored. This was particularly true in America, where general warrants gave customs officials broad powers to search property and seize goods in the hunt for smugglers. Wilkes' arrest launched a saga of court trials, acquittals, additional publications, more arrests, exile, imprisonment and popular protest. It made Wilkes famous.

Reform and Liberty

To the English public, Wilkes represented liberty-loving Englishmen. They embraced his attacks on institutions that they, too, believed needed reform. They rallied behind his causes including calls for the elimination of general warrants, for annual parliaments, for extending the franchise and for the repeal of measures alienating Americans.

American Colonists embraced Wilkes' cause because it was their cause — the cause of English liberty. Just writing, printing or calling out the number "45" was code for "English liberty." Americans followed his exploits in newspapers. The slogan "Wilkes and liberty" was heard at clubs and social gatherings. Punch bowls, produced in England for the American trade, featured portraits of the Englishman. Correspondents, including James Madison, wrote about and circulated pamphlets in his support. Organizations raised and sent money to aid him. Arthur Lee, Richard Henry Lee's younger brother, was studying law in London and was swept up in the Wilkesian cause. He visited Wilkes in prison and wrote home to share his enthusiasm at having met the celebrity.

Virginia's gentry planters had several reasons for supporting Wilkes. The gentry had land interests west of the Allegheny Mountains. The Ohio Company, organized by wealthy Virginians to purchase land west of the Appalachian Mountains from the British government, and the Loyal Company, a land speculation company formed in Virginia, had been attempting to access western lands since the late 1740s.

But when Native Americans fought against European encroachment in Pontiac's Rebellion of 1763, George III responded with the Proclamation Line, forbidding settlement west of the Alleghenies. He hoped that by ebbing the flow of European settlers, the western border of North America would become peaceable. Otherwise the government, already heavily in debt, would be required to pay a substantial military force to guard the frontier. But, like Wilkes, Americans wondered why, after winning the French and Indian War, they should be forced to make concessions to the vanquished.

Americans were, for the most part, solidly Whig and when Wilkes reminded the king that he was "responsible to his people," they cheered. Americans appreciated Wilkes' support for the repeal of measures such as the Stamp Act and Townshend Duties. He was a friend to America, and America returned the friendship in kind. Americans supported Wilkes' struggles against general warrants. It was an issue that concerned them, as well. And in Virginia, Wilkes' Scottophobia resonated.

Scottish merchants were changing the economic landscape of Virginia. These entrepreneurs set up stores and traded directly with small tobacco farmers. Gentry planters had long served as the go-betweens, linking small landholders with the gentry's London merchant partners. But as Scottish merchants took a larger and larger share of business, gentry influence in the local economy decreased and resentment grew. The gentry accused Scottish merchants of offensive and illegal business practices ranging from fraud to smuggling. Many gentry assumed that there was something unethical about the Scots' techniques. It was a Wilkesian attack born out of frustration and prejudice.

Wilkesian Demonstrations

How popular was John Wilkes in America? A Stamp Act protest at Virginia's Westmoreland County Courthouse in September 1765 gives a sense.

Richard Henry Lee orchestrated an evening pageant. In John Mercer's account in The Virginia Gazette, two of Lee's slaves led the procession, hefting "long clubs, clothed in Wilkes's livery." The livery-clad pair marched at the head of a mob pushing a cart that carried two effigies. A sign on the first identified it as Bute's successor, Prime Minister George Grenville, architect of the Stamp Act. The second represented George Mercer, the Collector of Stamps in Virginia. In each hand George Mercer carried a sign: "Money is my God," and "Slavery I love." Several of Lee's slaves guarded the effigies, officiating in the "several offices of sheriffs, goalers, constables, bailiffs, and hangmen."

Lee himself followed the likeness of George Mercer "to take his confession, and publish his last speech and dying words." The Virginia Gazette article noted that the mob was not comprised chiefly of well-bred freeholders and gentleman politicians. These were the common people — everyday Virginians — the riffraff. He described them as "those ranks and degrees of people generally, and not improperly, known and distinguished by the appellation of Tag Rag and Bobtail."

Lee understood the power of popular events. Ceremony was extremely important in Colonial Virginia. Whether court day, militia musters, horse races or cockfights, these events drew the community together in common purpose by using symbols that resonated. Symbols don't work if the community does not recognize them, and the fact that Lee featured Wilkes so prominently indicates that in rural Westmoreland that evening everyone, including "Tag Rag and Bobtail," understood and embraced the concept of English liberty that Wilkes represented.

Like many celebrities, Wilkes' star burned brightly for only a few years. As the American Revolution progressed, the former Colonists found new American symbols of liberty and independence. But Americans have never tired of embracing the populist figures who speak plainly about the issues. Sometimes we celebrate them as heroes and sometimes not. But their ability to clearly resonate the public's fears and concerns focus our attention on the meaning of liberty.