Instruments appear against a backdrop of fabrics, some of which might have decorated rooms where guests were entertained. Both the instruments and the fabrics are part of Colonial Williamsburg’s collection. Here, a hunting horn with a 12-foot tube coiled three times and an inscription from the celebrated Viennese maker Johannes Leichamschneider lays against a red worsted textile with a ribbed texture.

The hurdy-gurdy, which produces a sound similar to bagpipes, has a crank-driven rosined wheel to excite the strings, four of which drone a constant pitch. The player would craft the melody by pressing the ebony and ivory keys. Linens and cottons, similar to the fabric shown behind the hurdy-gurdy, were used in clothing and as household furnishing textiles. The red stripe, woven by Colonial Williamsburg’s weavers, is similar to bed hangings in a chamber at the Peyton Randolph House.

Made in England or America sometime between 1780 and 1840, this rosewood fife is adorned with brass ferrules on both ends. Broadcloth, seen in this military uniform, was a dense, heavy woolen used in men’s clothing and protective coverings for furniture.

The English guitar, along with harpsichords and pianofortes, boasted the status of most favored musical instrument among women and girls in both England and America. A double weave technique was used to produce the pictured wool textile to create a durable and reversible fabric, known as Scotch carpeting, often used in floor coverings as an alternative to expensive hand-knotted carpets.

This violin evolved from the work of several makers — including Tommaso Eberle and Joseph Gagliano, both of Naples — and has been returned to a baroque configuration. It is displayed on a silk and worsted damask textile, affordable only to the wealthy, that can be found as window curtains, wall coverings and chair upholstery in the Governor’s Palace.

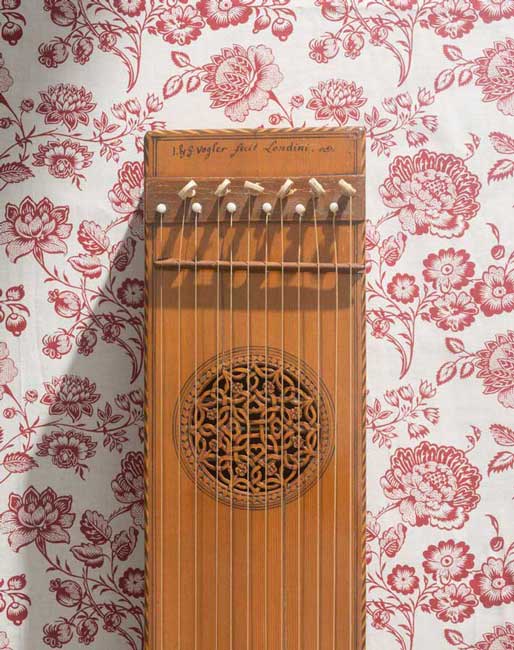

The stringed equivalent of a wind chime, the Aeolian harp was placed in window sills with the window open just enough to focus the breeze

across the strings. Fashionable printed cottons, as the one shown behind the harp, were popular as clothing and home furnishing textiles by the second half of the 18th century.