The Magazine of Colonial Williamsburg

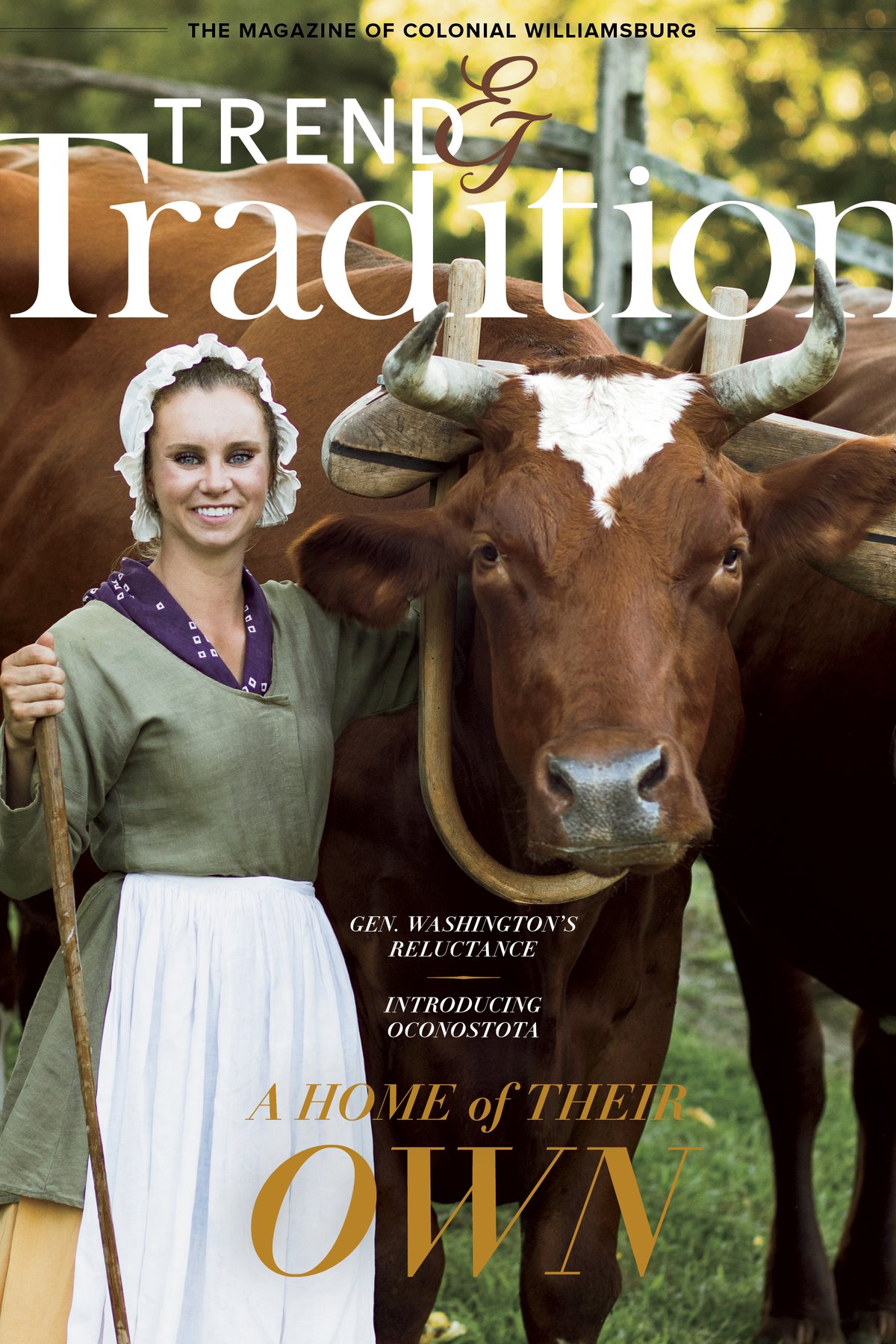

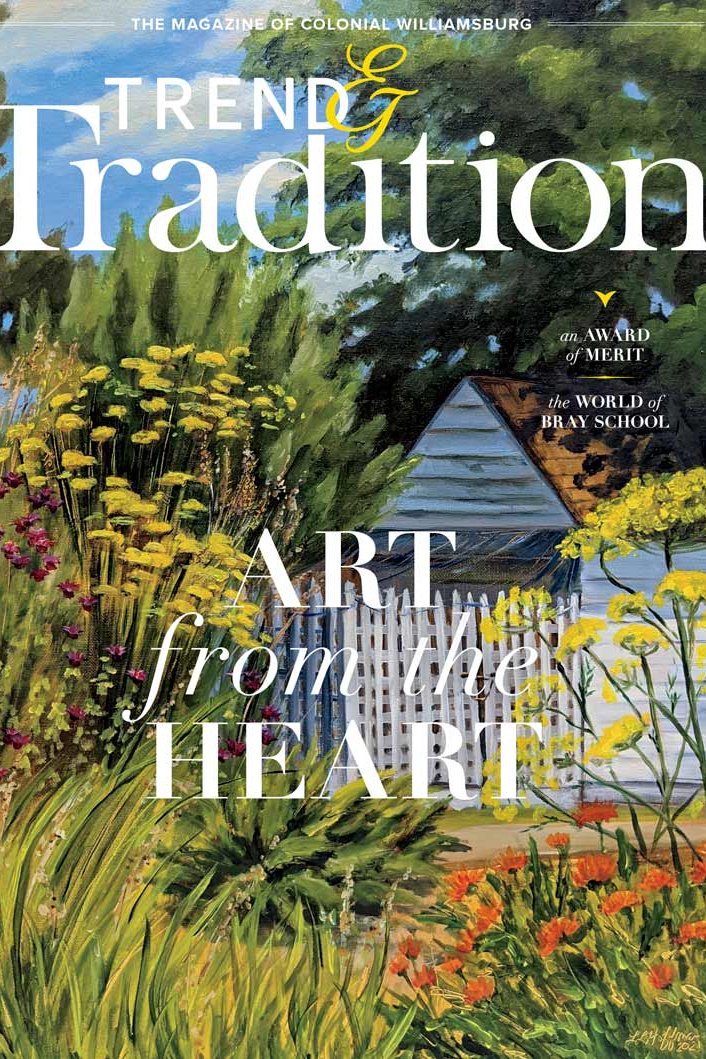

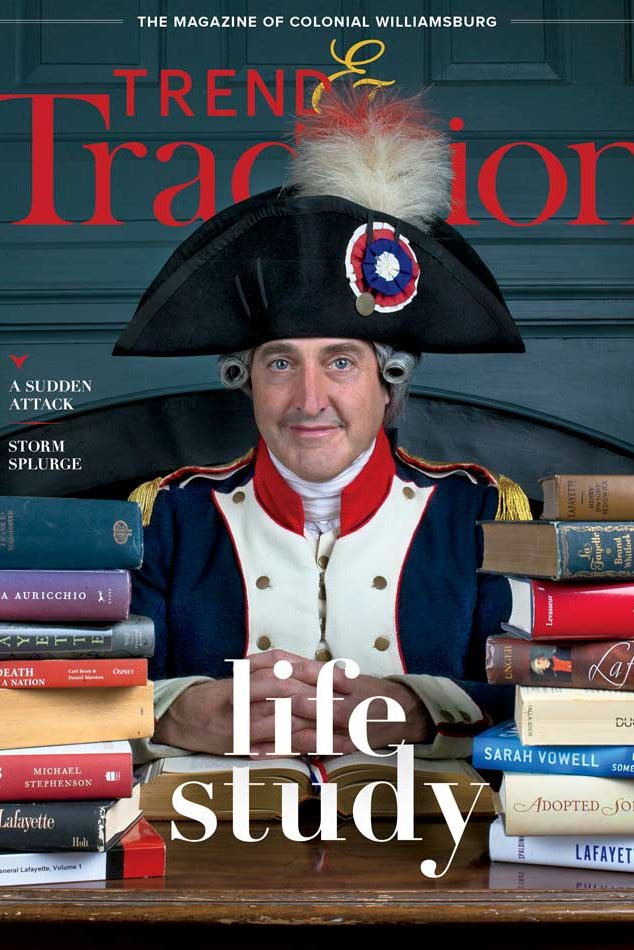

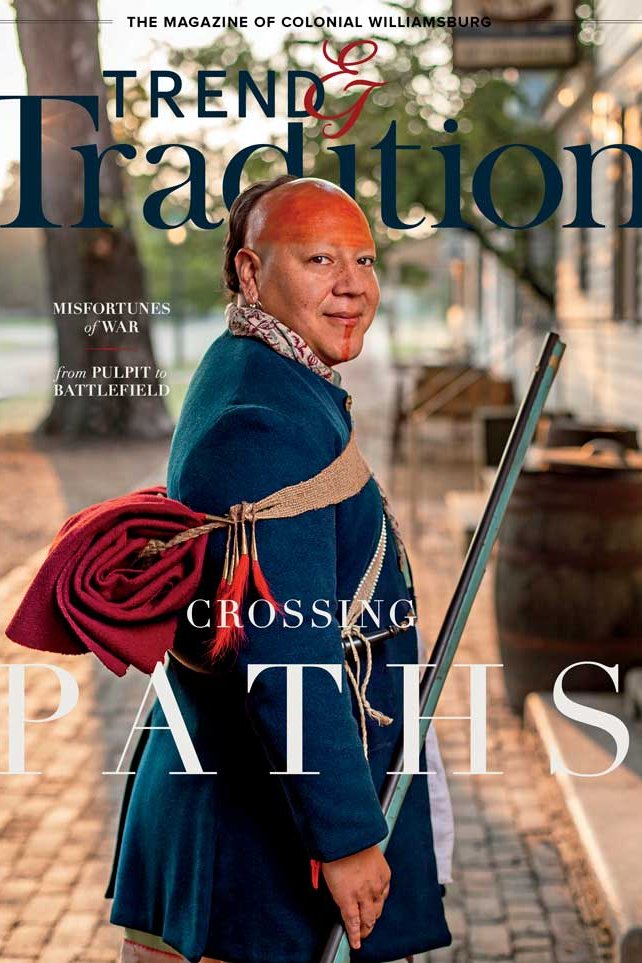

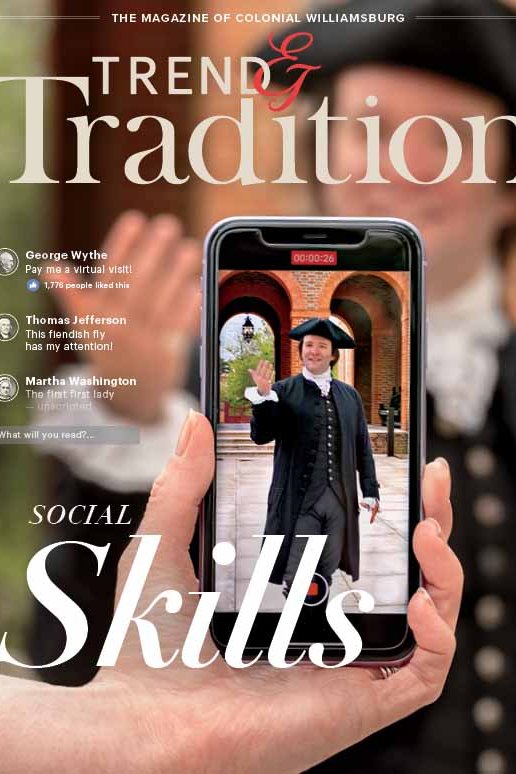

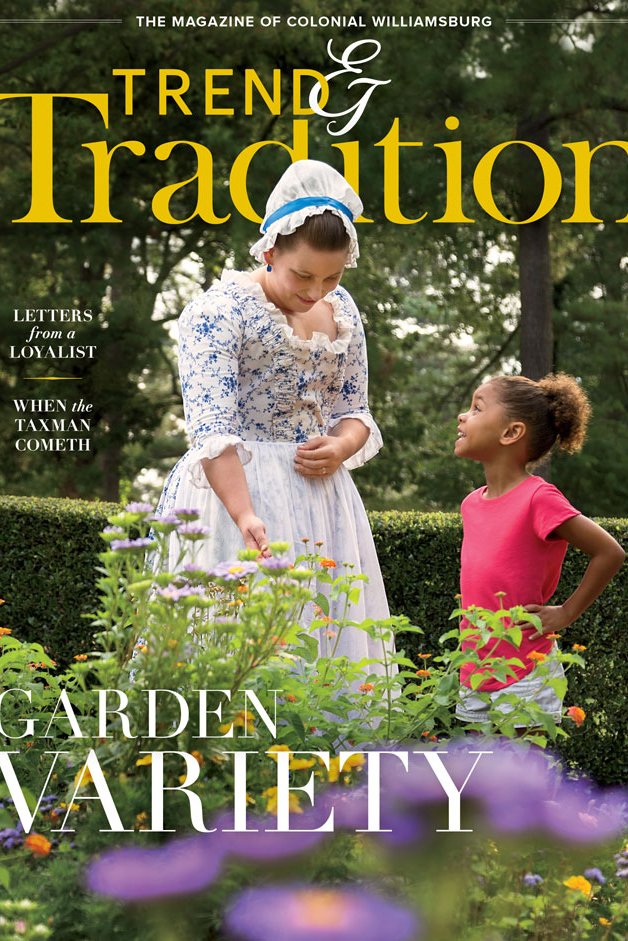

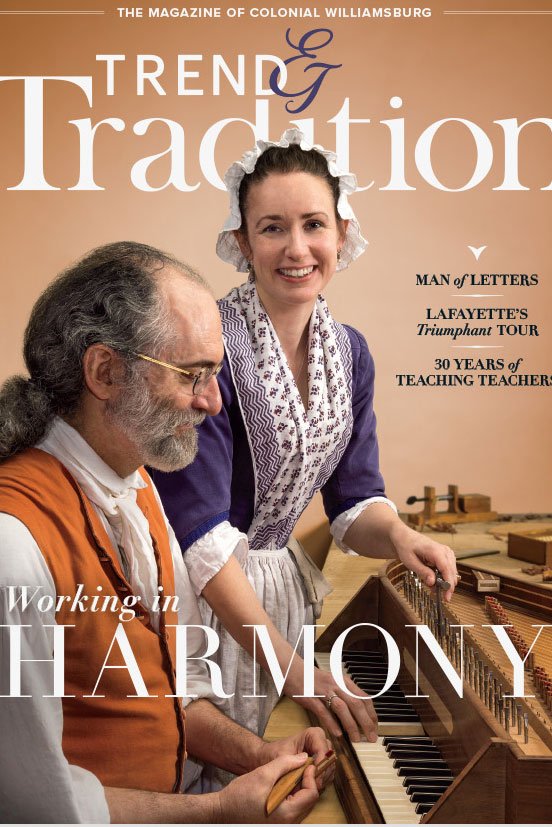

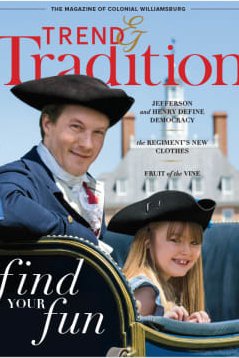

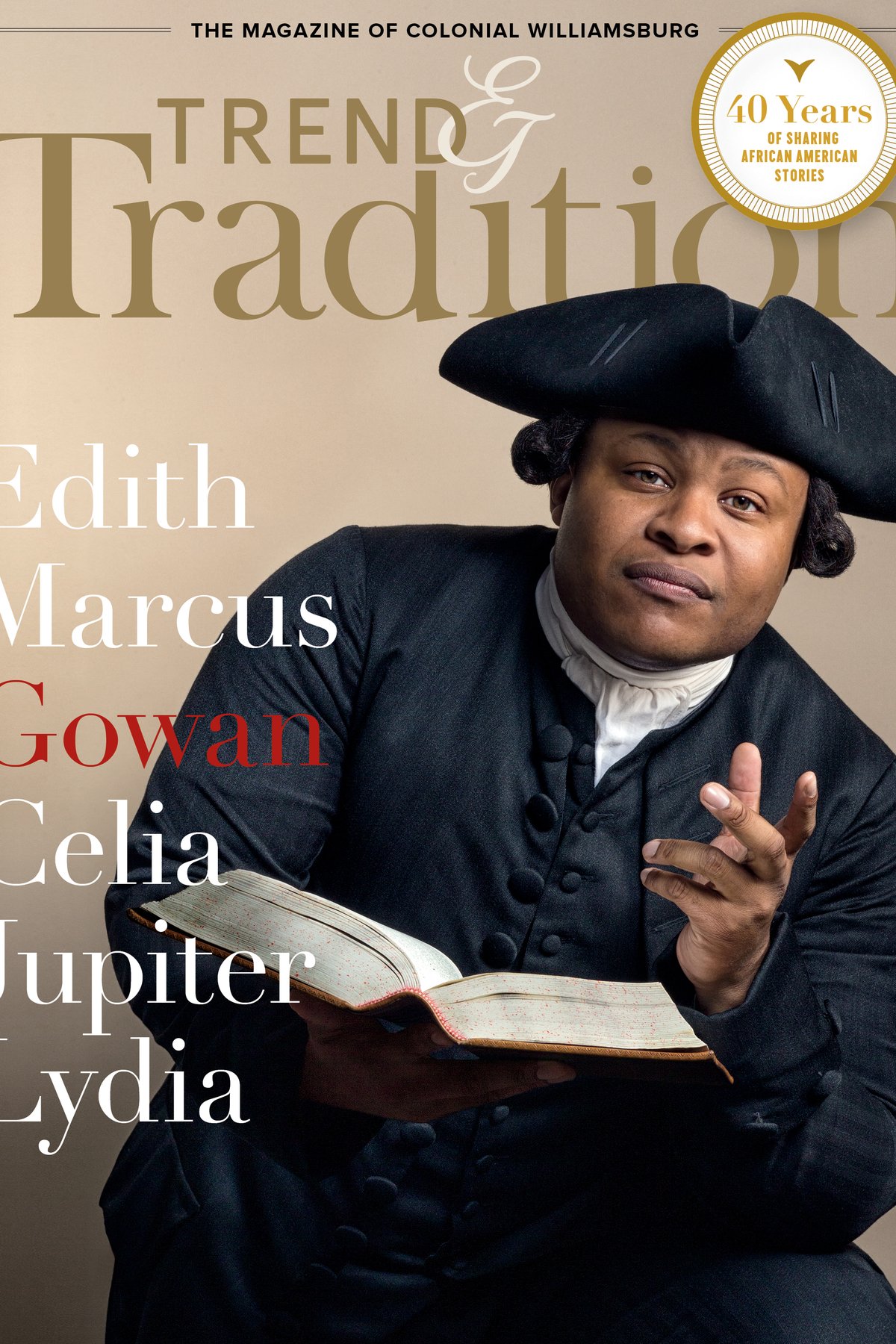

Trend & Tradition

Current Issue

In this issue, learn more about a new exhibition on 18th-century fame, Colonial Williamsburg's expanding view of research, and tales of legendary pirate Blackbeard.

More To Explore

All Issues

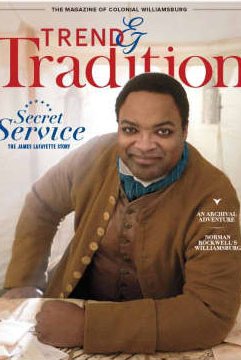

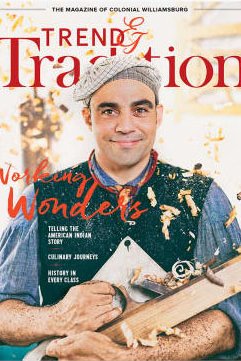

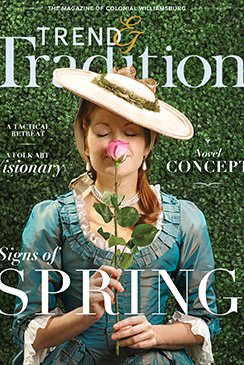

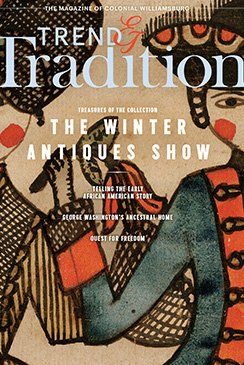

Colonial Williamsburg’s full-color quarterly magazine offers articles, photography, and art that showcase the life of Williamsburg’s historic core and its people — then and now. The printed magazine is mailed to individuals and organizations who donate $50 or more a year to the charitable, tax-exempt, and publicly supported Colonial Williamsburg Fund. The online version of the magazine offers a sample of stories from each issue.

Autumn 2024

Summer 2024

Spring 2024

Winter 2024

Autumn 2023

Summer 2023

Spring 2023

Winter 2023

Autumn 2022

Summer 2022

Spring 2022

Winter 2022

Autumn 2021

Summer 2021

Spring 2021

Winter 2021

Autumn 2020

Summer 2020

Spring 2020

Winter 2020

Autumn 2019

Summer 2019

Spring 2019

Winter 2019

Autumn 2018

Summer 2018

Spring 2018

Winter 2018

Autumn 2017

Spring 2017

Winter 2017

Autumn 2016

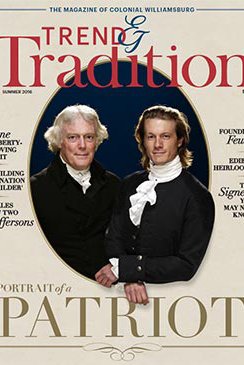

Summer 2016

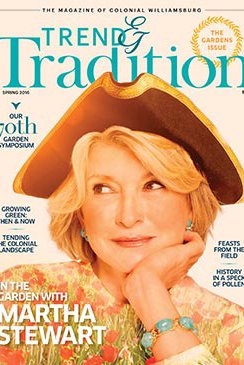

Spring 2016

Winter 2016