Though not an artist himself, Virginia-born William Lee was more familiar than most 18th-century Americans with the craft of painting portraits, though his own likeness remains a mystery.

Lee was the enslaved body servant to George Washington, one of the era’s most popular portrait subjects. During the American Revolution, Lee spent more time with the commander in chief than his own wife, Martha, did. Lee was at Washington’s side throughout the war, tending to his personal needs, polishing his boots, caring for his uniforms and other clothes, tying back his reddish hair and sometimes powdering it white. After the war, Lee continued as Washington’s valet until crippling injuries to his knees forced him to relinquish that role during Washington’s first presidential term.

As much as Washington himself or the artists who painted him, William Lee was responsible for how Washington looked in many of his portraits. And by 1785, Wash-ington had sat for so many portraits that he joked, “In for a penny, in for a pound.... I am so hackneyed to the touches of the Painters pencil, that I am now altogether at their beck, and sit like patience on a Monument whilst they are delineating the lines of my face.”

John Trumbull

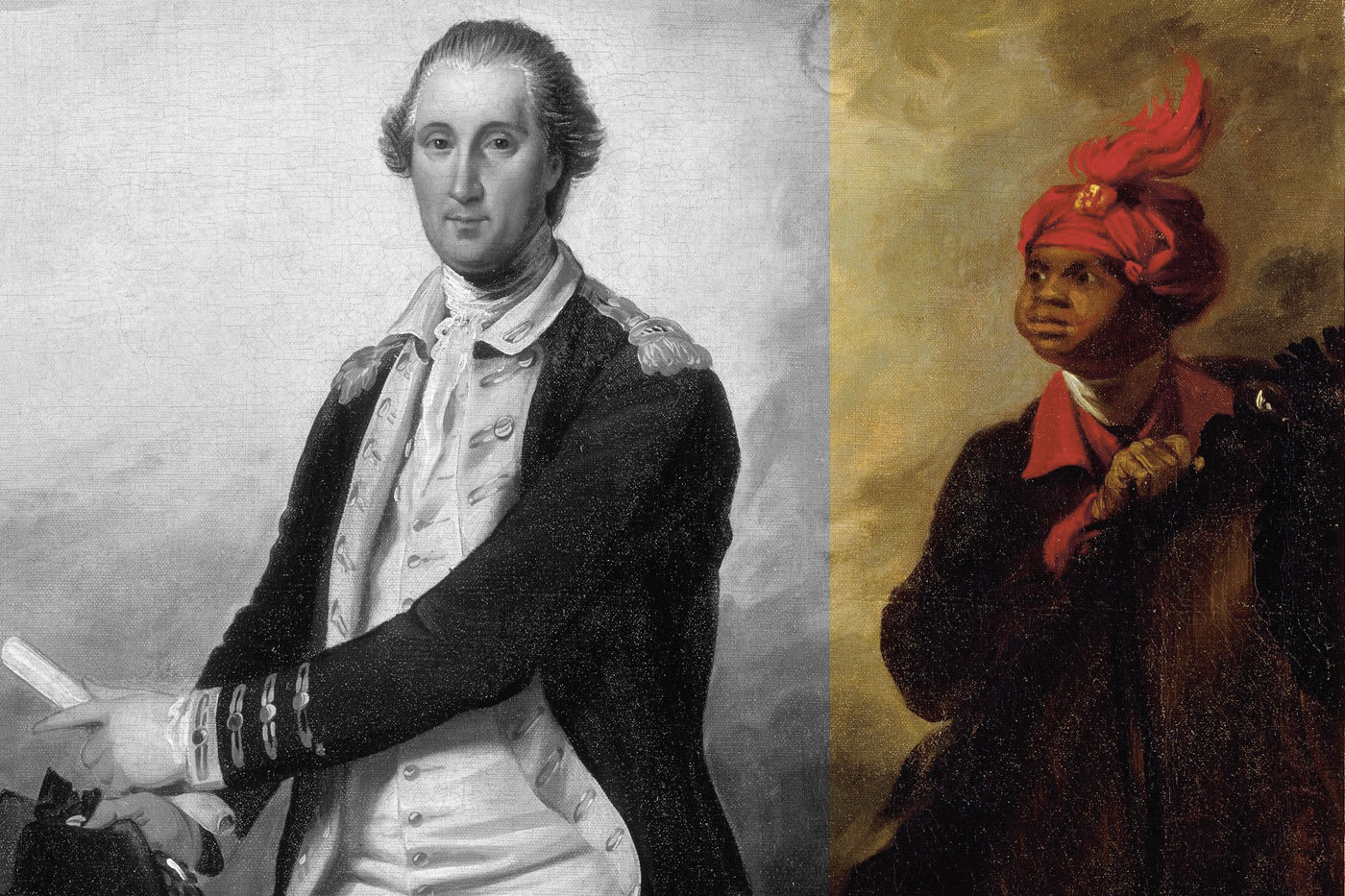

Ironically, neither man was physically present for the only portrait commonly presented today as a painting of the two of them: John Trumbull’s 1780 portrait George Washington and William Lee. By including Lee in his portrait of Washington, Trumbull acknowledged that Lee was a well-known figure to British and American soldiers, not only serving as Washington’s valet but often riding by his side, always with him during the war.

In this double portrait, Trumbull memorialized both men’s wartime identities. Washington stands in a pose of command, wearing his buff-and-blue Continental army regimental uniform, pointing toward the military fortress of West Point high above the Hudson River. Beside him is a Black man on horseback, wearing a blue coat with red collar and cuffs and a red turban, said to be Lee.

Neither man sat for the portrait because Trumbull painted it in London, completing it before his arrest and imprisonment for eight months on a charge of treason. He vehemently denied being a spy, but he was sympathetic to the American cause. He served in the Continental army and was one of Washington’s aides-de-camp. As a member of Washington’s inner military circle, Trumbull would have seen Lee daily. So perhaps it should come as no surprise that Trumbull’s portrait conveyed one of Lee’s defining qualities and skills when it showed him in command of a horse.

Lee, like Washington, was a fearless rider whose equestrian skills astonished his contemporaries. His legendary riding talent was one of the reasons visitors to Mount Vernon saw him as “a most interesting relic” of Washington. After the war, veterans and visitors would seek out Lee (sometimes in tandem with Washington’s chestnut battle horse, Nelson), eager to meet the celebrated horseman. Lee became an integral part of Washington’s wartime mythos. Trumbull’s portrait acknowledges that intertwined history.

Yet Trumbull did not create an accurate likeness of Lee. Instead, the artist chose to paint Washington’s valet in the form of a familiar stock figure used repeatedly in 18th-century art to symbolize “Blackness” — the image of a person with very dark skin and exaggerated facial features, wearing accessories that marked the figure as African, such as a silver collar, pearl necklace or earrings or, as in this painting, a turban. Rather than an accurate likeness, this portrait represented Lee as a racialized stereotype, one commonly used by artists to show Black people defined by their enslavement or service to white people.

Charles Willson Peale

Take a portrait painted around the same time as Trumbull’s, by another Revolutionary War soldier, Charles Willson Peale, who knew both Washington and Lee. In 1779, the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania commissioned Peale to render a grand painting of Washington to hang in the council chamber in Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. The 9-foot-tall painting officially memorialized “how much the liberty, safety and happiness of America” was owed to “His Excellency General Washington.” Multiple copies were made of the painting. It was meant to be widely seen and to solidify Washington’s image as commander in chief.

In Peale’s portrait, Washington wears his buff-and-blue Continental army uniform, the blue silk sash marking his rank slung across his chest. Peale included in the background a man in profile holding the reins of a horse, a chestnut like Nelson. The man wears a dark blue coat with red facings and has skin closer to the brown of the horse than the pale skin of Washington.

Washington sat for this portrait when he and Peale were both in Philadelphia in 1779. Peale also took pains to accurately depict the background Battle of Princeton site (a battle in which he too fought). The man in the background is not identified, but given Peale’s desire to accurately depict both Washington and the battle site (and at least a passing likeness of the horse Nelson), there is good reason to think that he is William Lee.

Lee was certainly known to Peale. Like Trumbull, Peale served under Washington. Indeed, both artists show the man in charge of the horse wearing the same coat, and both distinguish the color of his skin as darker than that of Washington. But unlike Trumbull, Peale had the chance to paint William Lee from life. In 1779, Lee was with Washington in Philadelphia, and he may have been particularly delighted to have his portrait put on public display in the city, as that was the year he married a free Black woman from Philadelphia.

There is another reason to think that Peale’s portrait is of Lee: Lee was a man of mixed race. Washington purchased William Lee (born c. 1750–52) in 1767 from Mary Smith Ball Lee, the wealthy, recently widowed wife of John Lee. Throughout his life, Washington alternated how he referred to Lee, calling him Billy, William and Will. (Lee himself preferred William.) But Washington never changed his description of Lee as a “mulatto,” a term used in 18th-century America to indicate that a person was of mixed race, with one white parent and one Black parent.

Since American law dictated that enslavement was inherited or not according to the status of a baby’s mother, all enslaved “mulatto” people had a Black mother and a white father. At Mount Vernon as at many other Virginia plantations, people of mixed race tended to labor as domestics, working as valets like Lee, or butlers like Lee’s brother Frank, or maidservants like Martha Washington’s dower slave Ona Judge. William Lee undoubtedly looked more like the brown man in Peale’s portrait than the stereotyped Black stock figure used by Trumbull.

Robert Edge Pine

There is a third artist who painted George Washington in the Revolutionary era who might have included William Lee in his paintings, but he died before he could complete his work. Robert Edge Pine, an award-winning British artist, immigrated to America after the war intending to immortalize in paint “some of the most Striking Scenes of the late Revolution,” in which Washington would, naturally, be “the Capital Figure.” To complete his life’s great work, Pine wanted to “gain a personal knowledge of the principal actors” of the Revolution and paint as many of them from life as possible. Given Lee’s place in Washington’s wartime mythology and the popularity of London-made prints of Trumbull’s portrait of Washington and Lee, Pine undoubtedly would have included William Lee in one of the paintings he had planned.

Such a decision would have been personal as well as artistic for Pine, who likely was a man of mixed race. Pine was the son of John Pine, a highly skilled London engraver who was principal engraver to London’s Grand Lodge of Freemasons, of which he was a member, and held royal appointments to King George II. John Pine also was friends with William Hogarth, who made him the subject of a 1755 portrait later copied into widely circulated prints.

In his features, his hair and his coloring, John Pine looks like a man of mixed race, a heritage Hogarth reinforces with a pearl earring, which, by the mid-18th century, was a marker of Blackness, like the turban Trumbull used in his portrait.

The Pines never acknowledged their mixed race, but other clues support the theory. One was that, while still living in London, Robert Edge Pine trained Prince Demah, America’s first identifiable enslaved portrait painter and a Black patriot who fought against the British during the Revolution. Demah went to London in the 1770s to get the training that he could not get in Boston. John Singleton Copley had refused to teach Demah in Boston, but Pine took him on, impressed by his “genius” but also perhaps more willing to work with a Black man because of his own heritage.

Of all the artists who had painted Washington’s picture, none had ever come as effusively recommended, or by so many important men, as Pine. Although he is now all but forgotten, in 1785 Americans viewed Pine as “the most eminent Artist, in his Way, we have ever had in this Country.” A friend and former Virginia neighbor of the Washingtons, George William Fairfax, first recommended Pine to Washington. Pine was Fairfax’s neighbor in England, where his pro-American art and outspoken support of the American cause “lost him business, and made [him] so many Enemies” in Britain that he needed to leave to make a living. He was to be welcomed, Fairfax said, not only because he was a great painter but also because he was “as true a ‘Son of Liberty[’] as any Man can be.”

Pine relocated to America after the war and settled with his family in Philadelphia, where he opened the young nation’s first art museum. The museum featured large paintings of scenes from English history, portraits of actors in roles from Shakespeare’s plays and a copy of the Venus de Milo, which likely was the first nude statue displayed in the United States. For a time, Pine also had the rent-free use of the Statehouse when Congress was not in session to work on the series of grand history paintings he planned to chronicle the American Revolution and its heroes. To that end, to secure portraits of George and Martha Washington from life, in spring 1785 Pine spent three weeks at Mount Vernon.

Perhaps because of his recommendations, Pine stood out from the never-ending stream of visitors when he arrived at Mount Vernon. Washington recorded in his diary that “Mr. Pine a pretty eminent Portrait, & Historian Painter arrived in order to take my picture from the life & to place it in the Historical pieces he was about to draw.” Pine brought Washington a copy of his allegorical print “America,” which the Washingtons hung on the green walls of their dining room.

It is unclear whether Pine and Lee met while he was at Mount Vernon because six days before Pine’s arrival, Lee suffered the first of his knee injuries while away from home. But Pine and Lee certainly crossed paths, if not then, a few years later when Lee was with Washington in Philadelphia for the Constitutional Convention and Washington again sat for Pine so he could adjust his portrait.

Washington left Mount Vernon for Richmond the day after Pine’s arrival to meet the proprietors of the Dismal Swamp Company, and it was Martha Washington, an exacting consumer and connoisseur, who commissioned Pine to paint portraits also of her cherished grandchildren and her niece. She hung those portraits in two of the mansion’s most important spaces: the front parlor, where important visitors were entertained, and the bedroom she shared with her husband.

George Washington died in that bedroom in 1799, the four portraits Robert Edge Pine painted of the four Custis grandchildren hanging on the wall. A group of people attended him at his death, including Martha, his physician, his secretary and several enslaved people. William Lee was not among them.

But Lee was in Washington’s thoughts. As he lay dying, Washington asked his wife to bring him copies of two wills he had prepared. He asked her to burn one and to keep the other. In it, he had made an unusual provision. He ordered that the people he held enslaved be freed when his wife died. But he made a special exception for Lee, who was granted “immediate freedom” in testimony of “my sense of his attachment to me, and for his faithful services during the Revolutionary War.”