If it were not for Mary Ambler, the pale 13-year-old daughter of Virginia Treasurer Jaquelin Ambler, we might not have the Constitution we have today. The young teenager — who was called Polly — was the lovely object of John Marshall’s affection. In 1780, the 24-year-old Marshall, then an army captain, pursued her to Williamsburg, where her father was then serving. Eventually with no troops to command and nothing to do but wait until Polly was old enough to marry, Marshall enrolled in George Wythe’s famous law lectures at the College of William & Mary.

Wythe’s class gave Marshall a convenient excuse to visit Polly, but Marshall could hardly keep his mind on the arcane subject matter. In the margin of his class notebook he scribbled Polly’s name over and over. Six weeks into Wythe’s course Polly’s family abandoned Williamsburg for the new capital at Richmond. Marshall quit his studies to follow her there.

Marshall was probably not the kind of suitor a prominent man like Jaquelin Ambler sought for his youngest daughter. Marshall was a rough-hewn frontier soldier born dirt-poor and raised in a two-room log cabin with his 14 brothers and sisters. He had no formal education apart from a single year of grammar school and a truncated course on Virginia law.

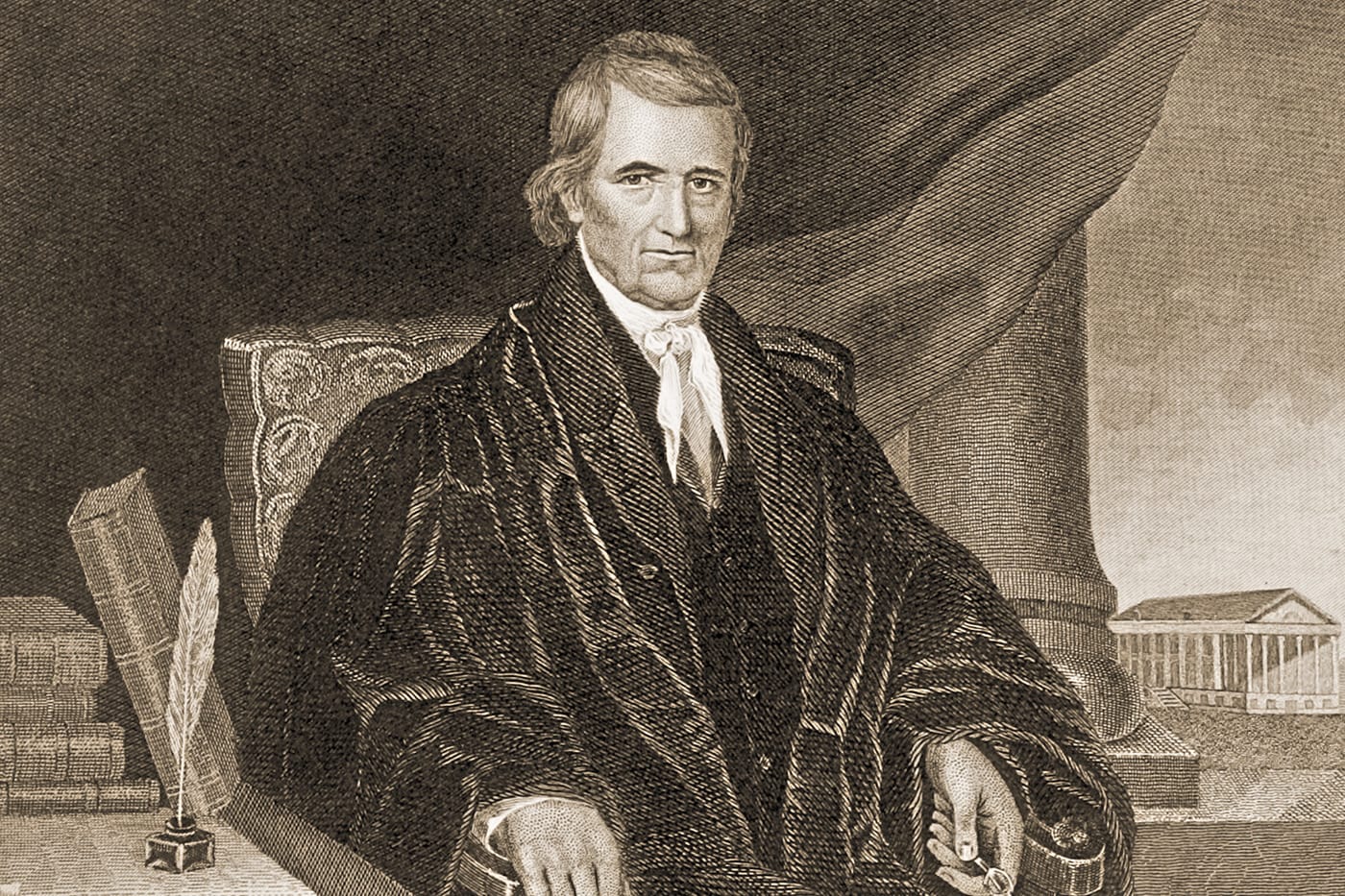

But despite his spotty education he was endowed with an innate intellect, sparkling eloquence and a winning personality. He would go on to become a leading attorney, an important statesman, a brilliant diplomat and the most influential chief justice in Supreme Court history.

He lived in a time in which the country was politically polarized — much like today. And the Supreme Court’s membership reflected that political conflict, much as it does today.

During Marshall’s 34 years as chief justice — longer than any other chief — he heard more than 1,100 cases. He wrote 547 opinions, and all but 36 of those were unanimous. What makes this record even more impressive is that every justice appointed to the Supreme Court during Marshall’s tenure was appointed by a Republican president who sought to overturn Marshall’s opinions.

Yet Marshall, a Federalist, prevailed by the force of his intellect and by forging common ground where none seemed possible.

Today, John Marshall is celebrated as the man who brought the U.S. Constitution to life. He defined the powers of government, protected private property and contract rights, incorporated international law into the common law, established the foundations of Native American law, defended the rights of aliens and safeguarded free speech. No one in the founding generation had a more enduring impact on the nation’s legal and political systems than Marshall, and no one did more to hold the country together in America’s frail infancy.

AN EARLY ENTRY ONTO THE POLITICAL STAGE

Marshall ran and won election to the House of Delegates in 1782 and was the youngest man chosen to join the executive council. In 1783, he married Polly and launched a family that would eventually include 10 children. During the Virginia convention to ratify the federal Constitution, Marshall was the indispensable man who wined and schmoozed enough delegates to win a narrow majority in favor of ratification.

Early in the new republic Marshall emerged as a leader of the Federalist Party and Thomas Jefferson’s principal rival in Virginia politics. After Marshall served a single term in Congress, President John Adams appointed him secretary of state after a Cabinet shakeup in 1800.

After Jefferson trounced Adams in the election of 1800, Marshall looked forward to returning home to Richmond, his beloved Polly and their brood of children, but it was not to be.

Federalists viewed Jefferson’s election with the sickening feeling that the republic would not survive him. Jefferson was a radical Republican, a populist disrupter who embraced the French revolutionaries and defended the rights of states to nullify federal law. As secretary of state he had undermined George Washington’s neutrality policy, and as vice president he had attacked President Adams. Jefferson now commanded a majority of Republicans in both houses of Congress. In the Federalists’ view, he could not be trusted.

Before leaving office, Adams sought to build a partisan wall around the Constitution by packing Federalist judges on federal courts. The lame-duck Congress quickly created 16 new circuit courts of appeal and 42 justices of the peace for the tiny District of Columbia.

When Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth’s resignation created an opening on the court in the fall of 1800, Adams asked John Jay, the venerable governor of New York, to take his place. Jay had been the first chief justice. He already knew the job was thankless. After he turned Adams down, the president told Marshall he must take the job.

Marshall had no reason to remain in Washington and little interest in the Supreme Court. His family had stayed behind in Richmond, which was a bustling metropolis compared with the nation’s dreary capital — what the Speaker of the House Albert Gallatin called a “hateful place.” Washington was a disease-infested, sparsely populated swamp with unpaved roads, few public buildings and no amusements.

Moreover, the job of chief justice promised little authority or prestige and few compensations. Marshall could earn more in private practice. The Supreme Court heard only about six cases annually and these were primarily of little significance. No one yet thought of the Supreme Court as a co-equal branch of government. Indeed, the architects of the capital city had not even bothered to build a courthouse and so the court was consigned to share a cramped nondescript committee room on the ground floor of the Senate with the courts of the District of Columbia.

PROTECTING THE CONSTITUTION

Despite these concerns, Marshall accepted the appointment out of loyalty to Adams and the memory of his commander-in-chief, George Washington. Marshall knew the court was the last bulwark to protect the Constitution from the wild-eyed Republicans. For the final month of Adams’ presidency, Marshall had the singular experience of serving simultaneously as secretary of state and chief justice.

President-elect Jefferson was infuriated by Marshall’s appointment. He had intended to name Virginia’s own chief justice, Spencer Roane, to that post. Moreover, Jefferson detested Marshall, who was his second cousin, and the feeling was mutual. Jefferson’s wealth had belonged to Marshall’s great-grandparents, but Marshall’s grandmother, a wild-spirited woman, had been disinherited. Thus, Jefferson’s extravagant lifestyle was the consequence of Marshall’s poverty.

With Republicans firmly in command of both the executive and legislative branches, they were determined to rid themselves of the Federalist judges. Congress passed the Judiciary Repeal Act of 1802 to eliminate the 16 circuit courts appointed by Adams, and the Republicans quickly moved to impeach two judges — one state and one federal. Then the House impeached Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase. Chase, also known as “Old Bacon Face,” was a fierce bear of a man, a prickly partisan who did not suffer fools. He was as beloved by his colleagues as he was hated by Republicans. Chase’s impeachment was a dress rehearsal for impeaching the other Supreme Court justices, including Marshall. Jefferson even entertained the thought that the president should have the authority to remove any judge at will.

UNIFIED AND UNANIMOUS

This constitutional crisis threatened the independence of the judiciary and the rule of law itself. How could the court resist a popular president in control of Congress? Marshall needed the court to speak with one unified voice if it were to check the power of the president.

Marshall persuaded the justices to share living quarters, and he rented rooms at Conrad and McMunn’s boardinghouse for $15 per week, which included firewood and wine. For the next three decades, the justices lived and ate all of their meals together as a fraternity. Though the justices had followed the British practice of each judge issuing a separate decision “in seriatim,” Marshall insisted that they issue one single opinion. To this end, Marshall would patiently talk through cases with his colleagues.

Since the Republicans had ignored the Constitution and fired the circuit court judges, the justices would be expected to ride circuit from one town to another hearing trials, which was how the Supreme Court had operated before the creation of the circuit courts. Riding circuit was tiring and humbling, often requiring the justices to conduct trials in taverns and sleep in modest inns. The justices disagreed as to whether they should accede to riding circuit or refuse and bring the federal judiciary to a crashing halt. Sensing the danger of a divided court Marshall persuaded them to abandon the threat of a strike. They needed another way to affirm the judiciary’s independence. Marshall soon found the perfect vehicle in the case of Marbury v. Madison. The case was brought by William Marbury, an appointed justice of the peace who accused Secretary of State James Madison of withholding his commission.

Marshall’s decision in Marbury established the principle that the courts can strike down acts of Congress that are unconstitutional. He famously proclaimed that it was “emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” This is the power of judicial review, but it was the least controversial aspect of the decision.

The Marbury decision also stands for the proposition that no one, even a Cabinet officer or the president himself, is above the law. This infuriated Jefferson, but he could do nothing about it. Marshall’s opinion was unanimous and so brilliantly crafted that it won praise from Federalists and Republicans alike. The authority of the court to strike down acts of Congress and the executive branch was now too well established to question.

A PERCEPTION OF PARTISANSHIP

Unlike Marshall’s court, the 21st-century Supreme Court has reached unanimous decisions in only 36 percent of cases since 2000. In nearly 1 in 5 cases, the court has split 5-4 along ideological lines. All four of the justices appointed by Democratic presidents typically vote as a block, as do at least four of the five justices appointed by Republican presidents. As a consequence the U.S. public perceives that the Supreme Court is just as partisan as Congress. According to Gallup polling over the past five years, 40 to 50 percent of the American public disapproves of the job performance of the Supreme Court, and in its most recent survey only 37 percent of the public has a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the Supreme Court.

Last year’s Supreme Court confirmation battle over the appointment of Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh was characterized by bitter partisanship with nearly every senator voting along party lines, and Gallup reported that Americans were evenly split over his nomination, depending almost entirely on their party affiliation. The politicization of the Supreme Court threatens its legitimacy and undermines the public’s faith in the rule of law itself.

Many Americans fear that the United States may soon face a constitutional crisis between the president and Congress concerning the investigations by the Office of Special Counsel and congressional committees. If that happens, we must depend on the Supreme Court to defend constitutional values, and the court’s legitimacy will be critical for holding our country together.

What is needed to restore our faith in the federal judiciary? We need to follow the example of the Marshall court. The Supreme Court must speak with one clear unified voice in defense of our constitutional values placing country before party. We must depend on the chief justice to embrace moderation and forge consensus. That will require vision, pragmatism and political acumen as well as patience. Let’s hope that when the time comes, John Marshall’s ghost is whispering in the ear of Chief Justice John Roberts.

Joel Richard Paul is the author of Without Precedent: Chief Justice John Marshall and His Times and a professor of constitutional law at the University of California Hastings College of Law.