An advertisement in the June 30, 1774, issue of the Virginia Gazette asked readers to be on the lookout for an escaped slave named Bacchus. The slave owner speculated that Bacchus would “attempt to get on Board some Vessel bound for Great Britain, from the Knowledge he has of the late Determination of Somerset’s Case.”

“Somerset’s Case” — specifically Somerset v. Stewart — was an English court ruling that inspired enslaved people like Bacchus to escape to Britain, where it appeared by the judge’s ruling that they could live free.

Somerset was James Somerset, who had been born in Africa and taken to Virginia in a slave ship in 1749. In Norfolk, he was bought by Charles Stewart, a merchant. Stewart (sometimes spelled as Steuart) later moved to Boston and then to London, taking Somerset with him as his personal servant.

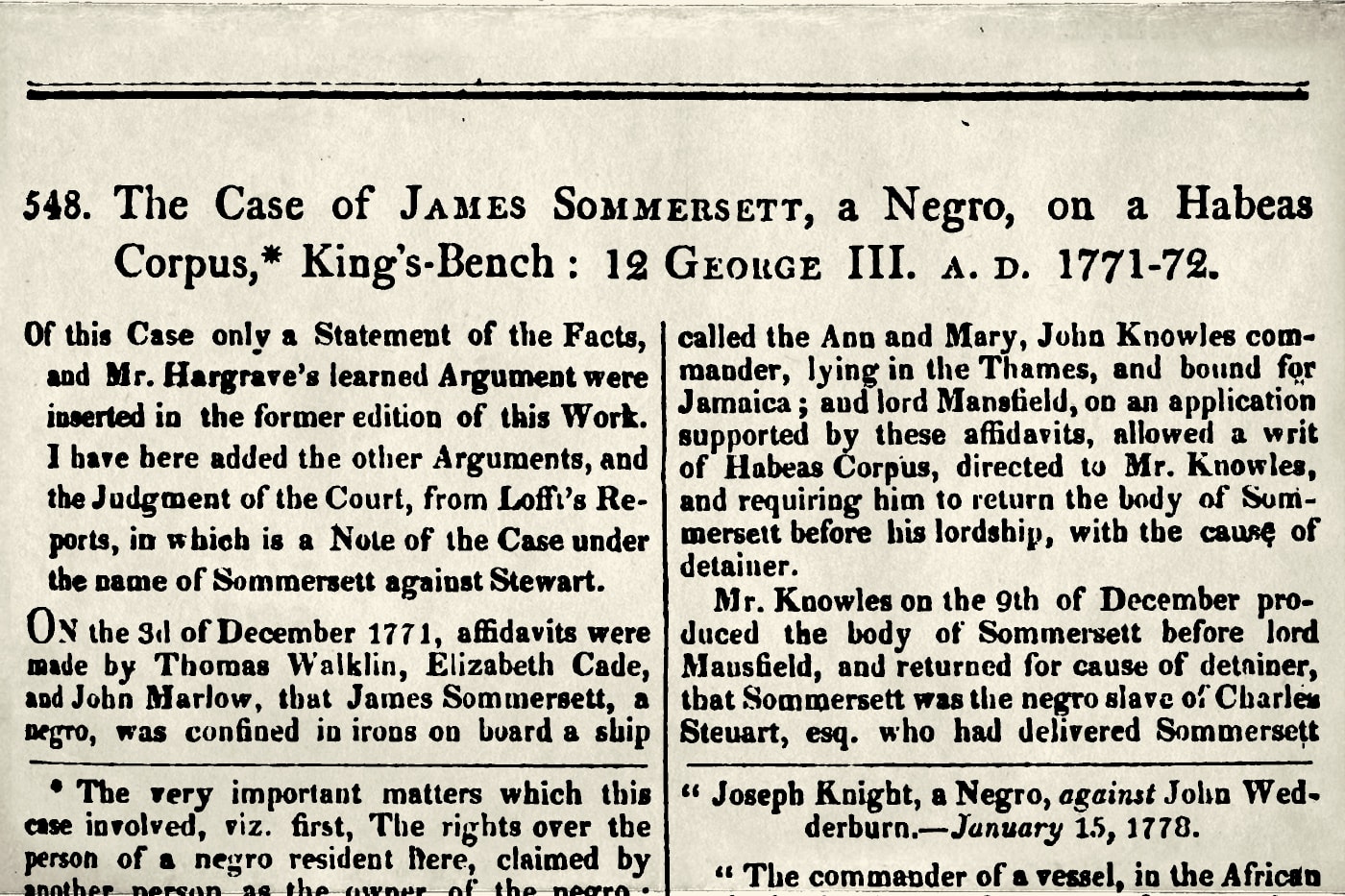

In London in the fall of 1771, Somerset escaped but was captured and shackled in a ship in the Thames River. Stewart’s intent was to ship Somerset to Jamaica and sell him there. Abolitionists in London learned of Stewart’s plans and took Somerset’s case to court where the enslaved man was granted a writ of habeas corpus, which required the ship’s captain to bring Somerset before a court. The writ of habeas corpus was a landmark decision in itself.

On June 22, 1772, Lord Mansfield, chief justice of the King’s Bench, the highest common law court in England, delivered his decision. As recorded by a young solicitor named Capel Lofft in the courtroom, Mansfield declared that “the state of slavery is of such a nature, that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political.” Slavery was “so odious,” Mansfield continued, according to Lofft’s recording, that it could be maintained only if there was a specific law authorizing it. This not being the case in England, “the black must be discharged.”

This was a historic ruling, and in London hundreds of blacks gathered to celebrate. Even before the ruling, a correspondent reported in the Virginia Gazette that since the case had opened, “the Spirit of Liberty has diffused itself so far amongst that Species of People that they have established a Club near Charing Cross, where they meet every Monday Night, for the more effectual Recovery of their Freedom.”

Many interpreted the ruling to signal the end of slavery in Britain. In reality, the legal status of enslaved people was very much up in the air, and slavery was not clearly and completely outlawed in the British empire until 1834.

Still, by declaring that slavery could be legal only where specific laws authorized it, Mansfield’s decision gave enslaved people an incentive to flee not just to England but also, increasingly over time, to Northern states of the United States.

“The decision was seen as abolishing slavery in England and, after the Revolution, in the United States, too, in the absence of positive law [that specifically authorized slavery],” said Steven M. Wise, author of Though the Heavens May Fall, a book on the trial that has been optioned for a movie. “The decision jumped across the Atlantic.”

Both sides in the case recognized the decision would be seen as setting a precedent. “This was the first example of what we would call a legal test case,” Wise noted. “There were seven barristers, including the greatest barristers of the age, representing both sides at a time when few cases involved even a single barrister. And the slaveholding interests were terrified.”

Mansfield became a hero to abolitionists in Britain and America. Some noted that the judge had adopted his nephew’s mixed-race daughter and that this may have increased his sympathy for the plight of enslaved blacks.

WHAT DID HE SAY?

One source of confusion about Mansfield’s ruling is that no one was quite sure what the deciding judge had actually said. Because Mansfield handed down his decision orally and no one has ever found a version of the text in Mansfield’s own hand, those interpreting the decision must rely on accounts by others.

And those accounts vary.

Lofft’s version is commonly quoted by those who saw Mansfield’s decision as sweeping away slavery, and most of the other contemporary accounts are similar in their arguments, though not exactly the same in their wording. But one version, which appeared in the June 1772 issue of the Gentleman’s Magazine, has Mansfield saying that Stewart “had no power to compel [Somerset] on board a ship, or to send him back to the plantations.” The magazine’s version says nothing about slavery being either odious or illegal in the absence of a law stating otherwise.

According to this version, Mansfield did not abolish slavery in England or anywhere else. Based on this account, many historians have argued that Mansfield’s ruling was much narrower than abolitionists thought, and that he freed Somerset solely on the grounds that an owner could not ship a slave out of the country to a place where he might be sold.

There’s reason to believe Mansfield wanted to avoid a sweeping statement about slavery. He repeatedly urged the two sides to reach a settlement, so he wouldn’t have to rule on the case at all. And Mansfield seemed to confirm the narrow interpretation of his ruling when he referred to it in a later ruling: In 1785, Mansfield stated that the Somerset case had determined that a “master cannot by force compel [a slave] to go out of the kingdom.”

Moreover, some of the most inspiring and oft-quoted words from the case — that “this air is too pure for a slave to breathe in” — were spoken by William Davy, one of Somerset’s attorneys, and not by Mansfield. Davy was echoing a phrase thought to have been spoken by a judge at a 16th-century slave case that expressed the sentiment that anyone who breathes the air of England is free.

Still, there’s some reason to suspect The Gentleman’s Magazine was intentionally downplaying the significance of the decision. Wise noted that the magazine quickly published two lengthy attacks on the case.

IMPACT OF THE DECISION

Regardless of what exactly Mansfield said, there’s no doubt that his words had a huge impact on both sides of the Atlantic. Having failed to get the parties in the case to reach a private agreement, Mansfield, according to Lofft, said that he would give his judgment and added, in Latin, “Let justice be done though the heavens may fall.” And, Wise said, “on June 22 they fell.”

Colonial Williamsburg historian Emma L. Powers examined the repercussions of the case in Virginia for an article in the Foundation’s Interpreter newsletter. “In following how the Somerset case was reported and discussed in the late 18th century and afterward,” Powers wrote “we see legends created, professional reputations made and lost, property safeguarded and later destroyed, dreams fulfilled or crushed, and people putting their lives and liberties on the line.”

In May 1772, even before Mansfield ruled, James Parker, Stewart’s former business associate in Norfolk, Virginia, wrote Stewart that “the affair of yr. Damed Villain Somerseat came on the Carpet” during a dinner at the Governor’s Palace with members of the Governor’s Council.

Also in Williamsburg, reports and comments on the case continued to appear in the Virginia Gazette. A correspondent in the Aug. 20 issue of the Gazette implied slavery was part of God’s plan and demanded to know: “Can any human Law abrogate the divine?” And the Nov. 12, 1772, issue included a lengthy and approving analysis of arguments defending Stewart’s position.

By the time Bacchus escaped in 1773, Virginia’s slave owners were very nervous. Rumors circulated of slaves planning uprisings. Then, in November 1775, Lord Dunmore, Virginia’s royal governor, offered to free enslaved people who were owned by rebels and willing to join British forces.

Dunmore may have hoped that his Emancipation Proclamation would bring rebellious colonists back in line, but it had the opposite effect. It solidified the patriots’ opposition to the Crown and moved Virginia — and America — a big step closer to independence. It also spurred enslaved people to escape to join the British, especially those who already knew about the Somerset case.

The effects of the Somerset case continued to be felt after the Revolution. On the one hand, it inspired abolitionists, who used it as a basis for attacking slavery and who succeeded in freeing some enslaved people in court cases in Northern states. But it also prompted Southerners to strengthen their hold on enslaved people, as they did when they insisted on inserting the fugitive slave clause in the Constitution. This clause, which required the return of those who had escaped to free states, remained in effect until the 13th Amendment abolished slavery.

As for Bacchus, the historical record ends with the ads in the Gazette. “We don’t know any more about his last days than about James Somerset’s,” wrote Powers. “Perhaps Bacchus made it to England in 1774. If not and if he dodged reward-seeking captors in Virginia, maybe he took advantage of the next year’s opportunity — Dunmore’s Proclamation.”

Paul Aron is the author of a variety of books on early American history including Founding Feuds: The Rivalries, Clashes, and Conflicts That Forged a Nation.