The Magazine captures the spirit of Colonial Williamsburg: It is historic and enduring.

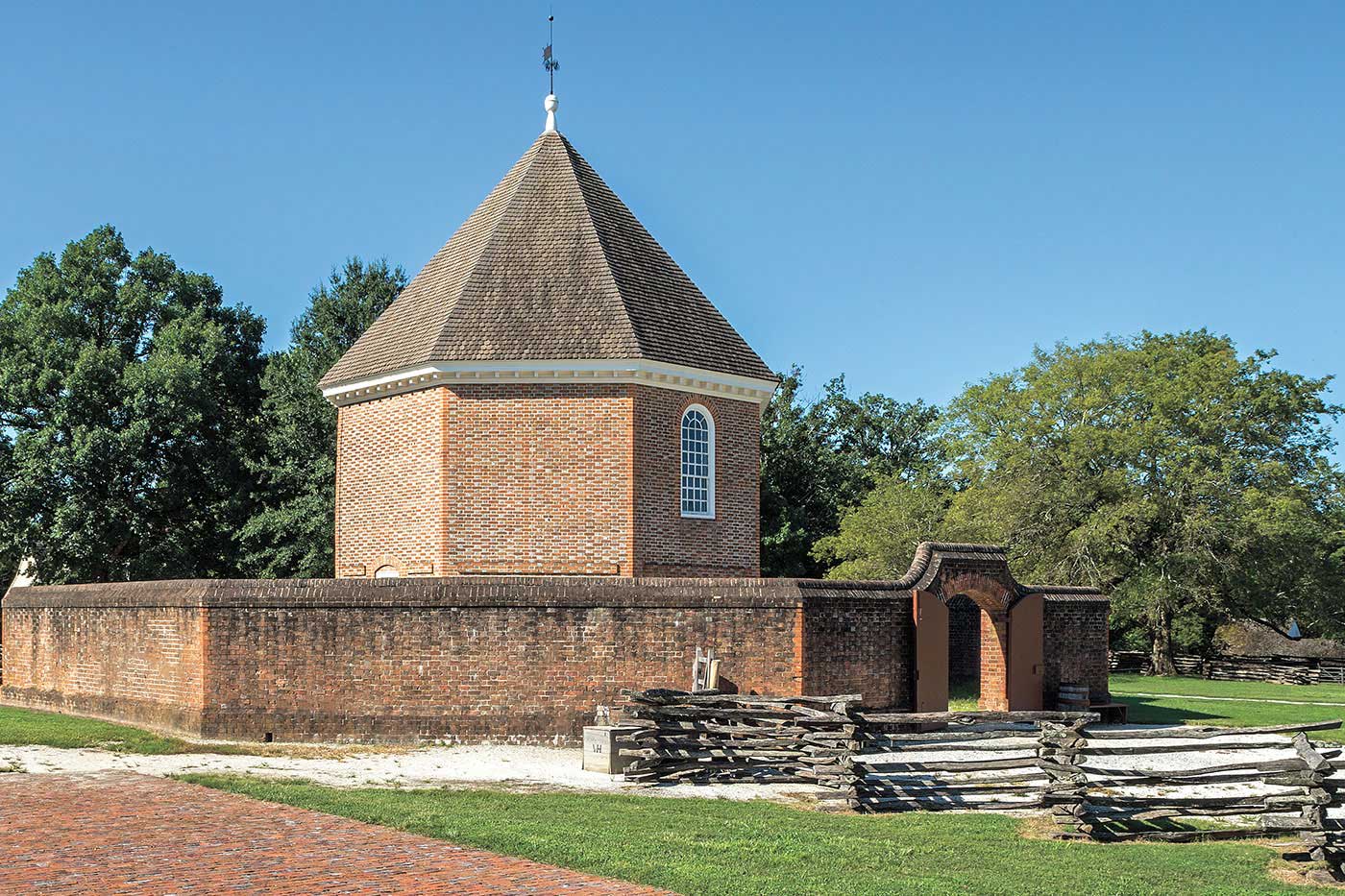

As one of Williamsburg’s original 89 buildings, it remains beloved by generations of visitors for whom the structure’s eight brick sides, shingled roof and surrounding wall are familiar sights.

But this iconic building likely would not have been as recognizable to 18th-century colonists.

What did the powder magazine look like 250 years ago? A new, multiyear restoration project ahead of Colonial Williamsburg’s centennial in 2026 seeks to answer that question. Archaeologists and architectural historians are digging deeper into the centuries-old Magazine to get a truer picture of its appearance on the eve of revolution.

“What did it look like?” asked Matthew Webster, the executive director of the Grainger Department of Architectural Preservation and Research. “We’re putting all these little pieces together.”

The Magazine has certainly changed over time. In 1714, Gov. Alexander Spotswood arranged to build a magazine to store arms gifted by Queen Anne. The next year, workers completed the octagonal structure. Its most dramatic moment came in 1775 when Virginia’s royal governor, Lord Dunmore, ordered the removal of gunpowder from the Magazine and ignited the Revolutionary War in Virginia. Since the Revolution, the building has housed a market, Baptist services and even a stable. These different functions likely altered the structure’s appearance.

Repairs and restorations further changed the Magazine. By 1890, parts of the wall had crumbled, one of the building’s eight sides had collapsed and the roof had caught fire. Colonial Williamsburg restored the building in 1935, though this restoration may not have accurately reflected its Revolutionary-era look.

It has been over 80 years since the building’s last significant restoration. Consequently, the Magazine “has never really been interpreted or studied in a modern way,” said Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology.

To reinterpret the structure “in a modern way,” researchers are undertaking archaeological and historical investigations. Ultimately, new information about the Magazine’s 18th-century appearance could bring more changes to the building as investigators’ understanding of it deepens. “There’s constantly new evidence popping up,” Webster said. “So we’re fine-tuning history.”

Some evidence is emerging from the first large-scale excavation of the Magazine’s yard. “Literally 6 inches beneath the surface that visitors walk on today are intact layers dating from the 18th century,” Webster noted. “Just the information we’ve already gained from archaeology will dramatically change the look of the Magazine.”

Archaeologists have unearthed evidence that dates to the 18th century, suggesting that the magazine’s original roof may have been made of clay tiles, not the shingles that visitors currently see.

“It totally makes sense that they would have had a tile roof,” said Jennifer Wilkoski, the Shirley and Richard Roberts Architectural Historian. “In the 18th century, they were very worried about fire.” Installing a tile roof would have been a logical fireproofing measure. After all, colonists stockpiled flammable material in a magazine; even the smallest spark could have set the whole building ablaze.

Researchers also hope to refine what they know about the magazine’s interior. The large windows, plaster walls and gun displays that have greeted visitors since the last restoration reflect the 1930s more than the 1770s.

“I would say that the interior of the Magazine right now is very much a Colonial Revival interior,” Wilkoski explained. “It’s a little prettier than it probably was historically. I think this building was more like a warehouse.”

Since a magazine’s primary purpose was to store munitions, Wilkoski said the windows probably would not have been as large as they currently are. “That just invites people to get into the building and attack it,” she reasoned. If it had smaller windows, they would have let in less sunlight, creating a darker interior.

Similarly, the gun racks may not have featured in the 18th-century interior. To make that determination, the restoration team is removing sections of the plaster walls to look for signs of colonial-era shelving systems.

Architectural historians also are relying on illustrations, letters and other primary sources to understand the powder magazine’s 18th-century features, including its exterior wall. A wall was erected in 1755, likely in response to the French and Indian War. Over the centuries, the wall crumbled and was rebuilt, though not necessarily in a historically accurate way. It currently stands at 10 feet high.

Records indicate that the wall may have been shorter. Webster pointed to one source: an account written by the son of a man hired to work on the wall in the 19th century. “He tells us that the wall was 5 or 6 feet tall, and if you look at drawings from the time period, you see these guys standing next to it, and it’s not towering 5 feet above their heads.”

Archaeological excavations, interior investigations and old-fashioned sleuthing are revealing new clues about the Magazine’s 18th-century appearance, but it is still too early to know what research will tell us about how the building should look. “We need to do more research,” Wilkoski acknowledged, “but we’re very excited to be able to start thinking about these things.”

Though the restoration may bring changes to an iconic building, one truth endures: The Magazine will still reflect Colonial Williamsburg’s spirit. As a more precise renewal of the 18th-century structure, its restoration reinforces Colonial Williamsburg’s commitment to authenticity — even if it requires change.

HOW YOU CAN HELP

Restoring the past is central to Colonial Williamsburg’s mission. Your support makes projects like the Magazine’s excavation and restoration possible.

Gifts to the Foundation also enable military programming at the Magazine. These programs contextualize the building in the story of Williamsburg and early America. These and other programs ensure that the past stays alive for future generations.

To lend your support to Colonial Williamsburg’s work, please visit colonialwilliamsburg.org/TT. Simply click the box marked “other,” and indicate that your gift is designated to support military programming.