A new exhibition at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg celebrates the lives and works of Black American artisans and artists from the 18th century through the 21st. The title of the exhibition — “I Made This...” — comes from David Drake (circa 1801-circa 1875), an enslaved potter who lived in South Carolina. Drake often inscribed verses on his pots, and several began with these words. He is one of very few enslaved potters to sign and date his work. The exhibition features one such object, a 5-gallon alkaline-glazed stoneware jug which Drake signed ‘Dave’ and dated 1842.

“I Made This...”: The Work of Black American Artists and Artisans is made possible through a grant from the Americana Foundation and includes paintings, furniture, textiles, decorative sculptures, quilts, ceramics, tools, metals and other objects from Colonial Williamsburg’s decorative arts and folk art collections.

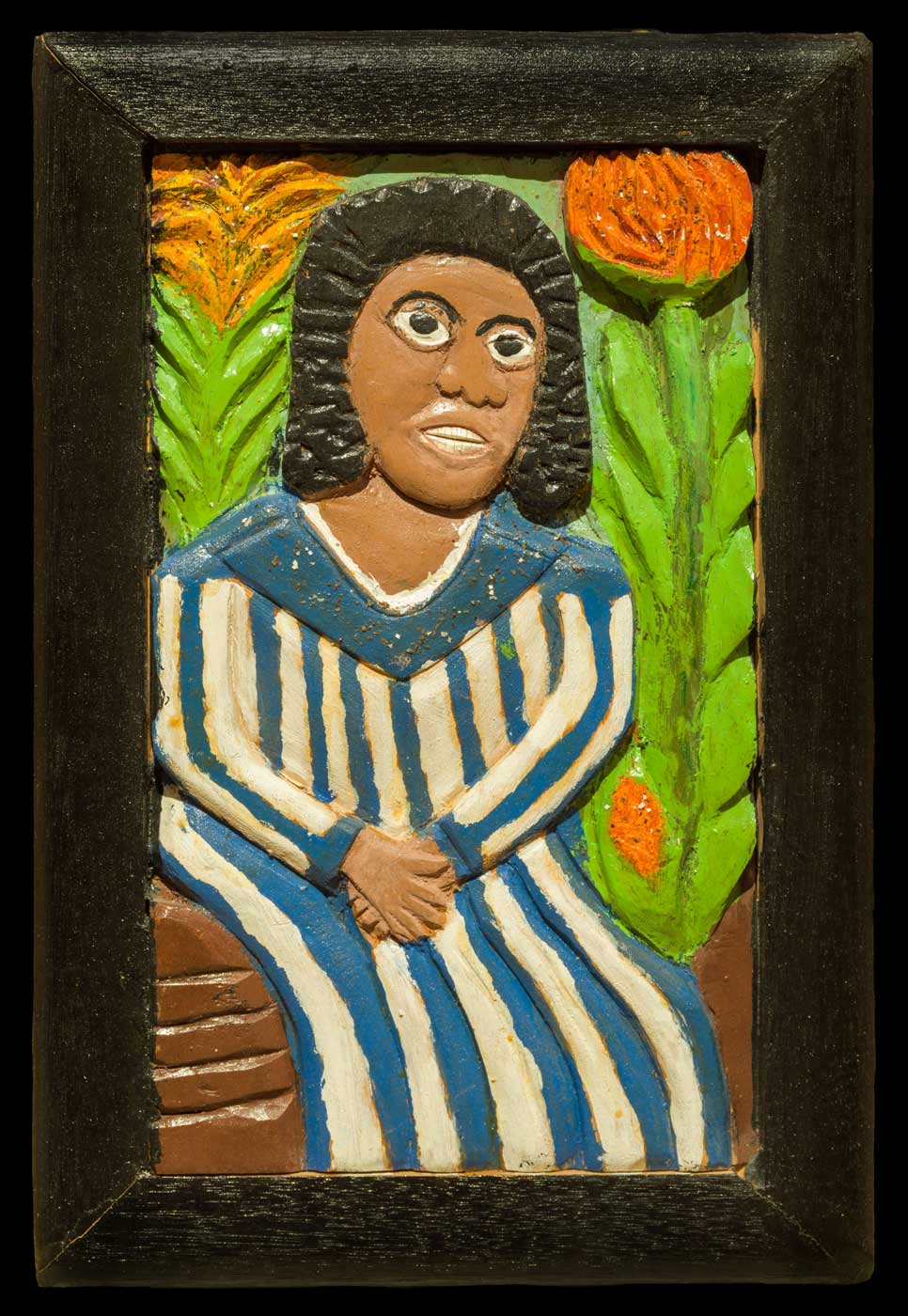

Dixie Land

Josephus Farmer

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

1985

Like many Black men born in the South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Josephus Farmer moved north in search of a better life. After leaving Tennessee for Wisconsin, he had a variety of jobs, but the ministry was his true calling. By the late 1960s, Farmer focused on spreading the word, but he carved and sold works of art in his spare time to help finance that work. Farmer dealt with the legacy of slavery in many of his artworks, including this mixed-media tableau. Here he depicted a Black farmer guiding a mule-drawn plow through a cotton field to call out the unfulfilled promise made by the federal government at the end of the Civil War: that each freed person would receive 40 acres and a mule.

Armchair

Attributed to the Monticello Joinery

Albemarle County, Virginia

1790-1815

John Hemmings and other enslaved woodworkers labored in the joiner’s shop at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. Originally trained by Irish joiner James Dinsmore, Hemmings assumed supervision of the shop in 1809. The shop made fine furniture for Jefferson, including cabinets, tables and, almost certainly, this chair. Other enslaved artisans on the estate likely made the linen webbing and foundation linen and the iron nails. The overall form was probably inspired by French or Italian chairs Jefferson saw during his European travels. Hemmings himself crafted much of the interior woodwork of Jefferson’s house at Poplar Forest in Bedford County, Virginia. Under Jefferson’s will, Hemmings gained his freedom and the tools of his trade in 1827. He chose to remain at Monticello with his still-enslaved family until his death in 1833 at the age of 57.

Baptism

Clementine Hunter

Natchitoches, Louisiana

1950-56

Born in 1887, Clementine Hunter spent most of her life working as a farmhand and cook at Melrose Plantation in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana. During its heyday, Melrose was a center for arts, history and culture, inspiring artists and writers to visit and stay at the property. Hunter’s first painting, begun when she was in her late 50s, was created on a window shade with discarded paint left by one of the guests. Her colorful images, like this one depicting an outdoor baptism, record everyday life and the people in her community.

Portrait of Marian Anderson

Elijah Pierce

Columbus, Ohio

1975-76

Elijah Pierce heard the call to preach early in life. He supported himself by operating a barber shop in Columbus, Ohio, and he carved wooden figures in his spare time. Pierce saw his wood carvings as a manifestation of his spirituality, but they also chronicled turning points in Black history, such as this image of celebrated vocalist Marian Anderson. Like many of her peers’ careers, Anderson’s was plagued by racial discrimination. In 1939, after being denied a chance to perform at Constitution Hall in Washington, the gifted contralto was invited by Eleanor Roosevelt to sing at the Lincoln Memorial. This carving portrays that concert, symbolizing the moment Anderson began to sing.

Crucifix of Carved Stone

William Edmondson

Nashville, Tennessee

probably 1932-37

Without instruction or experience, William Edmondson began cutting limestone as directed, he said, by God. Though he was featured in a one-man exhibition in the 1930s at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, he remained largely unknown and preferred to be at home in Tennessee. One of four versions of the subject, this one differs in its smaller size and the contrast between the smoothly finished figure of Christ and the roughly chiseled cross and base.

Portrait of Ellin North Moale and Her Granddaughter, Ellin North Moale

Attributed to Joshua Johnson

Baltimore, Maryland

1798-1800

Joshua Johnson, America’s first Black professional artist, worked in the Baltimore area for 30 years beginning about 1795. Born into slavery, he was freed in 1782. Little is known of Johnson’s career path, but he once referenced “having experienced many insuperable obstacles in the pursuit of [my] studies.” With its complex background and costuming, Johnson’s likeness of Ellin Moale and her namesake granddaughter is one of his most ambitious. Notably, Moale’s husband, Justice John Moale, signed Johnson’s manumission papers.

Big Daddy’s House at Hickory Hill

Bernice Sims

Near Brewton, Alabama

circa 1996

Bernice Sims came to art late in life after surgery left her unable to work. A chance meeting with noted Black artist Mose Tolliver, who lived nearby, spurred her on. Many of Sims’ works, including this one, reflect her memories of rural childhood and family activities. Others depict her role as an early civil rights activist.